A slowdown in the for-sale housing market has resulted in a surge of interest in partnership models aimed at delivering affordable housing. Simon Rawlinson and Neal Curtis of Arcadis explain how joint-venture models work and examine whether wider adoption will increase affordable housing supply

01 / Introduction

The year 2023 is likely to be an annus horribilis for the UK housing market. In the private sector, a triple whammy of rocketing borrowing costs, the end of Help to Buy and the introduction of the Future Homes Standard is expected to result in a 20% reduction in activity this year. Apartment developments have also been affected by further uncertainty associated with second-staircase requirements. Affordable housing developers, including registered providers (RPs), face similar viability challenges while simultaneously grappling with backlog maintenance issues, building safety repairs and long-term decarbonisation obligations. It is little wonder that new-build housing development is taking a backseat until for-sale markets find a new equilibrium.

A slowdown in the new-build market has serious implications for the delivery of low-cost housing. With grant levels covering only 20% of development cost, cross-subsidy based on revenue from private market sales has propped up affordable and social housing delivery for many years. With the for-sale market in trouble, new ways of improving viability and accessing capital are needed to maintain affordable housing supply.

Furthermore, for-sale homes subsidised under the government First Homes scheme are due to absorb 25% of homes delivered by the section 106 route. This means that even when the housing market recovers, RPs will need to find new ways to maintain delivery volumes for shared ownership and affordable rental homes.

One area that is seeing renewed interest is the partnership housing model, where a public sector body like an RP joins forces with a developer or investor on a 50:50 joint-venture basis. Partnership development models and joint ventures (JVs) have been used in the UK for many years, enabling local authorities and RPs to leverage the value of land assets to expand their capacity to build homes. In the current market, however, the JV model is giving the partners more options to address viability and quality issues by eliminating some aspects of development on-cost and by properly aligning the interests of the landowner and the development partner. Developers in the current market, for example, benefit from their ability to maintain a build programme by switching to affordable tenures. JVs are also enabling institutionally funded for-profit registered providers (FPRPs) to participate more widely in development. FPRPs typically focus on shared-ownership and affordable housing schemes that will yield a long-term, predictable income stream.

The recent announcement by Vistry that it is merging its partnership and for-sale housebuilding units is a powerful illustration of the benefits of the JV model in a slow market, using the pre-sale of housing to RPs and local authorities to reduce overall costs of capital while also addressing the affordable housing shortage.

The JV model is no panacea. All housing developments need to wash their face, and in many locations, with grant funding levels so low, the land element of a JV has little if any value. Similarly, developers only have so many levers to improve viability and cannot buck the market trend. However, where deals stack up, the JV model increasingly looks like the best way for the public sector not only to scale up its delivery capacity, but also to better leverage the value of existing assets in order to create revenue streams as well as capital returns.

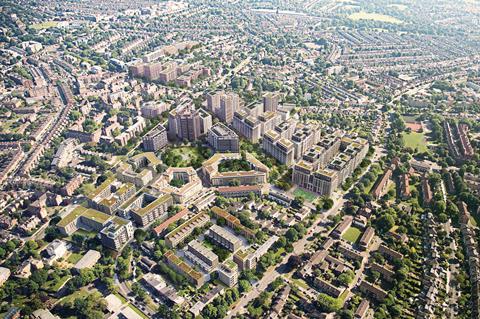

Case study: Clapham Park

The scheme includes phased public realm enhancements, decants, infrastructure enhancement and wider development improvements. One of the advantages of the JV approach is that it enables land value to be offset against the additional costs of a low-carbon heating strategy. This approach also enables the client to specify requirements for its retained assets and include its red lines and objectives within the legal agreements.

Arcadis’s role started with financial modelling to establish the development position alongside procurement advice, which selected the route of a JV partnership. Tendering took place in 2020, amid covid-19, and concluded in 2021 with an above-target return for the client. All three bidders remained engaged throughout the process. Arcadis is now delivering the JV supervisor role for the development partnership.

Multi-phased developments like Clapham Park require the JV to make decisions that account for the impact of development on future phases to ensure there is structure and continuity in the assets and the community. The operational stage of the JV remains flexible in response to market conditions and other circumstances.

02 / How affordable housing works and why the delivery model needs an update

Long before the cost-of-living crisis struck, the UK’s affordable housing model was under long-term pressure. Even with an £8.6bn funding allocation and the benefit of mandatory section 106 housing contributions via the planning system, nowhere near enough low-cost housing has been produced.

According to the National Housing Federation and Crisis, 145,000 low-cost homes are needed annually across all tenures from social rent to shared ownership, yet only 50,000 were delivered in 2020/21. One of the consequences of historically low levels of delivery is that 1.2 million households are waiting for affordable housing. Another is that the bill for housing benefit, the UK’s main form of affordable housing subsidy, now tops £23bn per annum, barely £10bn less than the annual running costs of the Ministry of Defence.

Expanding affordable housing supply is not straightforward. The funding gap to increase supply to 145,000 by grants alone is £34bn, according to the British Property Federation.

Even if an increase in grant were forthcoming, neither RPs nor their delivery supply chain would have the capacity to respond. Other routes to delivery are also constrained. The supply of affordable housing through the planning system is inevitably limited by the rate at which the market can absorb for-sale housing. Ironically, as reservation rates crater, housebuilders are turning to the affordable sector as a market for their surplus production.

>>Also read: Will Gove’s latest local plan reforms have a positive impact on delivery?

>>Also read: Top 150 consultants 2023: How will AI help your business?

RPs also have limited financial room for manoeuvre. Years of borrowing have left many RPs close to their gearing limit and struggling to cover interest costs on new development. Facing a huge amount of pressure to address fire safety, housing quality and carbon issues, new development is less of a priority.

Another constraint acting on both RPs and local authorities is access to equity to fund development. Neither RPs nor local authorities can directly distribute a profit, which means that they cannot accumulate the equity needed to access development finance markets. However, both RPs and local authorities have land and existing housing portfolios which potentially provide a lever to access external capital via a JV. One of the advantages of the approach is that an RP or local authority should be able to channel payments from the JV, such as interest payments on land, into revenue accounts, converting a capital asset into a much-needed revenue stream.

Looking to the long term, the JV model does not simply provide a short-term fix while for-sale housing markets are in the doldrums. It also offers a way to inject institutional “patient capital” into affordable housing development, providing the housebuilding industry with a stable platform on which to rebuild capacity.

03 / �ڶ����� blocks of a successful joint venture

A housing development JV is typically (but not always) a standalone corporate entity, owned jointly by a public sector body such as a registered provider (RP) and a private sector partner that might be a housing developer, a for-profit registered provider (FPRP) or an institution like a pension fund. The purpose of the JV is to enable development that allows the JV partners to better meet their own specific objectives, for example by being able to scale up development operations or by giving RPs a greater opportunity to input into the design and specification of a scheme in order to optimise its long-term operational performance.

The concept of a residential JV is to bring together all the capabilities needed to take forward development. The private sector partner is likely to bring development management, construction management and sales capabilities, while the RP is likely to have strengths in long-term tenant and estate management and in stakeholder engagement. The JV parties will also bring equity in the form of land, working capital and contributions in kind. Until recently, most JVs have been aimed at the for-sale market, delivering affordable housing via a section 106 agreement and providing a return to the RP to cross-subsidise further development. However, as the for-sale pipeline slows, JV partners are taking greater interest in tenures like shared ownership that provide a combination of sales, rental and asset management income.

Although JVs create opportunities for RPs to secure greater returns through direct participation in development, they also involve risk. The structure and culture of a JV will be put under considerable strain should things go wrong. Shared experience, transparency and tried-and-tested business models will make a JV more resilient.

50:50 business model

The cornerstone of a successful JV is that it has to be a 50:50 venture, with respect to board representation, liability for inputs and a share of development returns. The JV entity operationalises this by acquiring land, money and services from the partners and other third parties on a paid-for or sweat-equity basis. JVs can borrow against the security of the equity, often obtaining low-cost finance directly from the partners. The venture is typically a subsidiary company, either a limited liability company or a limited liability partnership. The subsidiary structure ringfences some of the development risk and also provides greater operational flexibility. The advantages of these arrangements include:

- Complete alignment of the commercial interests of the partners, providing greater flexibility and resilience.

- Reduced development costs and cash flow benefits resulting from low-cost borrowing, sweat-equity contributions and timing of payments

- Potential for additional income streams for the JV partners from the JV entity – such as interest payments and management fees

- Shared risk exposure, reducing risk premiums and aligning behaviours.

Trust and transparency

If the cornerstone of a JV is the 50:50 commercial model, the mortar that holds everything in place is trust facilitated by transparency. The vital element that underpins trust is the clarity that neither party can manipulate the JV to its specific advantage (for example, through the valuation of its contribution) and also that both parties are obliged to perform to the best of their abilities. Paradoxically, greater exposure to development risk is a further incentive for good governance within the JV as both parties hold each other to account.

The culture of trust within a JV is facilitated by a JV supervisor, a distinct and independent role that is appointed by the JV rather than by either the RP or the development partner. The JV supervisor does not undertake any conventional project roles like those of an employer’s agent. Their role is to facilitate the JV, to monitor its effective operation, and to provide recommendations on key aspects of JV management such as land values based on market comparables. By having an independent facilitator built into the JV model, many potential sources of difference between the parties can be more easily addressed and resolved.

04 / Specifics of the procurement process

The selection and appointment of a JV partner is of course a vital step in the development process. The key objective and outcome of the procurement is the creation of a long-term partnership based on alignment and trust. As a result, the process has to achieve a careful blend of collaborative and transactional elements.

The appointment of a JV partner and public procurement are fully compatible. As mentioned previously, the establishment of a commercial JV entity like an LLP will remove downstream requirements for a compliant public procurement process, but the initial process typically has to be undertaken in a fully compliant and transparent manner. In particular, this relies on accurately describing the requirements in notices, along with a clear statement of assessment criteria and their consistent application throughout the procurement process.

Under current UK public procurement processes, both the competitive dialogue and the competitive procedure with negotiation are a suitable basis for appointing a JV partner. Looking forward to the enactment of the Procurement Bill in 2024, new flexible procedures will give public sector clients a wider range of options to run a competition.

There are alternative routes to appointing the JV partner. Arcadis has developed an approach based on an investment partnership, which creates a commercial vehicle to which projects can be added. The investment partnership is another form of JV, typically based on a limited liability partnership (LLP) that can be formed outside of a formal public procurement process. This gives the client greater flexibility as well as reducing the cost and time needed for the procurement process.

Regardless of the appointment process, JV partners are typically shortlisted on the basis of their experience. The procurement process needs to allow for plenty of opportunity for engagement and discussion around the details of the JV structure and proposed teams. The negotiated procedure, for example, requires the client to define the starting point for negotiations, which has the advantage of providing guidance around the development of the bidders’ proposals. Once received, a misconceived proposal is very difficult to work back from, so getting right-first-time submissions is very important.

The quality elements of a submission will receive the greatest attention as partners seek to confirm cultural fit and alignment. The JV-specific track record of each potential developer partner is particularly important in this regard. However, the commercial elements are critical and quite complex – particularly with respect to items such as the valuation of the residual value of the client’s equity land contribution. JV negotiations benefit from the input of an advisory team with extensive experience of a range of JV partners and business models.

JVs are typically more complex, costly and time‑consuming to assemble than a conventional single-project tender. Accordingly, as clients develop their JV strategy, they should view it as a programmatic play to access expertise and development capacity and to leverage land equity, rather than as a one-off and tactical response to the current housing market crunch.

Increasing delivery of affordable housing through private capital

Two of the key constraints that will limit the potential for JVs and residential development generally, and in particular over the next few years, are the viability of for-sale development and access to low-cost capital. One advance in the housing sector that could shortcut through these constraints is the involvement of for-profit registered providers (FPRPs).

At the moment, the FPRP sector is tiny. Savills calculates that barely 0.2% of affordable homes were in FPRP management in 2020. However, there is a strong alignment between the income-seeking objectives of institutions such as pension funds and the stable, bond-like characteristics of revenue from tenures such as shared ownership. Housebuilders are also looking at the FPRP model as a means of derisking their section 106 affordable housing production, as levels of demand and prices paid by RPs become less certain.

Institutions have been prolific lenders to the RP sector via bond markets. Total debt is over £86bn, according to the Social Housing Regulator, but gearing and interest cover restrictions mean that further borrowing is limited. For institutional investors to expand their exposure, they will have to get more involved, either by acquiring existing assets through a stock transfer, or as a development partner – ideally in a JV to access readily available development skillsets or possibly through a forward-funding model.

Although the growth of FPRPs is a positive development for the affordable housing sector, it may introduce further challenges for traditional RPs. Firstly, there will be even more competition for the section 106 product delivered by housebuilders, and also in the future there could be more competition for scarce private sector JV partner capacity, particularly if an RP’s ability to participate is constrained by capital borrowing limits.

A potential solution is for an RP and an investor to team up outside the JV, combining finance and land resources on the input side of the equation and potentially income call-off and asset management on the returns side. There is little doubt that FPRPs could have a big impact, expanding potential development capacity for affordable housing, as well as creating alternatives to the mergers that many RPs have adopted in an effort to achieve scale in an increasingly cost-competitive market.

05 / Conclusions

The JV model is well established and has been given fresh impetus by the current housing crisis, bringing together developers that need to maintain volume with RPs and other providers which have a mission to ensure the supply of affordable housing.

JVs are complex arrangements that involve sharing risk. While adopting the model will create new options for the partners to improve the viability of proposed developments, a JV will not buck the market. This is why the culture and fit of the JV is so important, to ensure the corporate entity is resilient and that the partners are properly aligned to deal with challenges as well as opportunities. Getting the procurement and the set-up of the JV right is a vital first step on the journey to successful collaborative development.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Richard Jones and James Knight of Arcadis and Kris Kelliher of Devonshires Solicitors for their input into this paper.

No comments yet