From April 2018, all rented properties must meet a prescribed minimum energy performance standard. Adam Mactavish of Sweett Group, Charles Woollam of SIAM and Sarah Sayce, emeritus professor of Kingston University, discuss the implications

01 / Introduction

Under the Energy Act 2011, from April 2018, it will be unlawful to let properties that fail to achieve a prescribed minimum energy performance standard (MEPS) until qualifying improvements have been carried out. It is expected that this minimum standard will be equivalent to an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of E. As a result, owners of properties with EPC ratings of F or G will, in some circumstances, no longer be able to let these properties until their energy efficiency has been addressed.

With nearly 75,000 commercial premises having EPC certificates rated F or G (~19% of certified units) and a further 65,000 with an E certificate, this policy has the potential to have a dramatic impact on levels of investment in the energy efficiency of our existing buildings. Furthermore, since the policy was first mooted, there has been widespread discussion about its potential implications, with some anecdotal reports of transactions being delayed and with F or G-rated properties being considered as “risky” within the market.

To understand in more detail the likely implications of this policy for different types of property the Green Construction Board commissioned research from Sweett Group, SIAM and Kingston University.

The intention of MEPS regulations is to stimulate market changes to speed up the rate at which energy efficiency upgrades to inefficient buildings take place. Research points to the likely success of this strategy in many parts of the property investment market. MEPS should trigger cost effective investments in a wide range of building types, thereby reducing energy use and associated cost and carbon emissions. These measures will be beneficial for occupiers by reducing their costs and the wider economy and society by stimulating cost effective investment and reducing carbon emissions. In many locations the costs associated with MEPS regulations will be relatively small as a proportion of the rental and capital values of the property. The results will be optimised when the work is undertaken “in-cycle” as part of more extensive refurbishment or fitting out works.

The exact detail of how MEPS will operate is not yet fully defined. The analysis is therefore based on current expectations of how the detailed regulations will be implemented (see below).

02 / Implications for property owners

It is hard to predict the effect that any new regulations will have on existing property in specific locations and this is a particular challenge for MEPS regulations as much will depend on prevailing property market conditions both nationally and locally.

The introduction of MEPS is expected to increase general awareness of energy-related issues and it is likely that buyers and potential tenants of poorly-rated units will have greater regard to the potential cost of compliance before committing to transactions. In some circumstances, the cost of energy and the cost of mandatory energy efficiency improvements will come to influence market pricing. Anecdotal evidence would suggest this is already the case as potential purchasers look carefully at the risks attached to properties with F and G ratings.

The implications of MEPS are likely to vary with the economic cycle. Under buoyant conditions market demand tends to reduce the differential in value or rents between prime and secondary properties. At these times, the market has a tendency to disregard all but the most severe risks. At other times, when demand is lower, the market discounts properties that they consider to have secondary characteristics or above-average risks. In such circumstances there will be an expectation that any compliance costs are quantified and incorporated, if only partially, within transaction prices.

Property owners are unlikely to be able to forecast accurately the economic conditions when they may wish to sell or let a specific asset. Therefore, it is prudent to assume that known characteristics, such as a poor energy rating, could have an impact on liquidity or value even if this is not always realised in a buoyant market.

Expected implementation of MEPS in England and Wales

The Energy Act 2011 obliges the government to introduce energy efficiency regulations by no later than 1 April 2018 and, while the broad parameters of the new regulations are set out in the Act, much of the detail has been left for secondary legislation. For the purposes of this study, the following key assumptions have been made about implementation of the regulations.

Scope - the regulations will apply to all privately-rented non-domestic properties with an EPC rating.

Threshold - the minimum standard for energy efficiency will be an EPC rating of E and units with ratings of F or G will be directly affected. Properties with a current EPC rating of E might also be affected by the regulations after 2018 if, on reassessment, the rating falls below this point because of changes in the EPC calculation method or if the minimum standard is raised, e.g. to D.

Requirement - applicable properties failing to achieve the minimum standard will be required to implement measures to improve the asset’s performance until it achieves an EPC of at least E, subject to these improvements being “cost effective”.

Cost effectiveness - to be considered cost effective, the measures must pay for themselves through the resulting energy cost savings. This may be linked to eligibility for Green Deal finance. This means that these measures must be compliant with the “Golden Rule”, i.e. the value of projected energy savings over the life of the measure is greater than the costs of repaying a Green Deal loan over this period. Landlords will not be required to undertake energy efficiency works that are not cost effective, so in some cases buildings may retain F or even G ratings after all eligible measures have been undertaken.

Implementation - after April 2018 a landlord may not let (or perhaps even continue to let) a property failing to achieve the minimum standard of energy efficiency. A property failing to meet the minimum standard can continue to be let if the current tenant refuses permission for improvement works to be undertaken. Thus, in practice, a landlord will not need to undertake energy efficiency upgrades mid-tenancy unless the tenant agrees that the works should be undertaken.

Each of the above assumptions is subject to the government’s consultation on the implementation of MEPS and any subsequent publication of the regulations.

Table 1: Factors influencing the impact of MEPS

Beyond the vagaries of wider market conditions, Table 1 lists the key factors that are important when assessing the potential impact of MEPS.

| Energy saving potential | Owners are only liable to undertake improvements that are cost effective (see “Expected implementation of MEPS”, opposite). For buildings with a very high energy saving potential, as modelled by EPC assessment software, the potential level of investment to secure the saving can be relatively high as a proportion of rental income. For most properties, the energy cost saving and therefore associated expenditure is relatively low as a proportion of income and value. |

| Cost of compliance | The cost of energy efficiency improvements differs according to the type of building, its age and current specification. Further, building costs vary considerably from one region to another. There is therefore likely to be some regional variation as to what works are considered cost effective. * |

| Potential to add value | Rents and other property market characteristics vary substantially both within locations and across the UK. Market conditions will influence both the significance of any irrecoverable costs incurred and also the potential for generating a return on refurbishment activity. |

| Responsibility for repayments | The extent to which an occupier is prepared to meet the cost of improvements has significant implications for landlords. MEPS policy (and the wider Green Deal approach) is based on the assumption that building occupiers will be responsible for meeting the cost of loans taken out by landlords to achieve savings from which the occupier will be the principal beneficiary. The extent to which occupiers are prepared to contribute to energy efficiency investments will depend on many factors including: market conditions, their confidence that they will see the benefit of reduced energy costs and the availability of other similar properties in the locality. If there are large numbers of better-rated, but otherwise comparable properties nearby, it will affect the bargaining strength of the parties. |

| Vacancy rates | Landlords will be responsible for repayments of finance taken out to fund energy efficiency improvements when properties are un-let. Where properties will be vacant for long or frequent periods during the term of a loan, there will be an impact on net income. |

*There is an interesting implication of linking the MEPS obligation to the cost effectiveness of the energy saving rather than rent or property value. In regions with lower construction costs, owners could be obliged to implement some energy saving measures to meet their MEPS obligation that would not be cost effective in parts of the country where construction costs are higher.

Based on these factors five tests were defined by the research team to help understand the potential implications of the policy for commercial properties.

- How many properties are likely to be affected by the regulations?

- Is it likely that the EPC rating will be improved through cyclical refurbishment or redevelopment before 1 April 2018?

- Can an F or G rating be improved to E or D through Green Deal qualifying improvements?

- For properties that pass the Golden Rule test, is the cost of finance significant in relation to the rent?

- Is the proportion of finance repayments met by the landlord during void periods high enough to undermine the viability of future lettings?

A summary of the findings for each point is shown below.

03 / How many properties are likely to be affected by the regulations?

The non-domestic energy performance register maintained by Landmark contains details of ~500,000 EPC ratings for premises in England and Wales. It is not known how many EPCs will ultimately be lodged on the register and so the total number of properties affected is unknown. On average, more than 6,000 new certificates have been lodged each month in the last year. The study for the Green Construction Board had access to ~400,000 records taken from the database in Spring 2013.

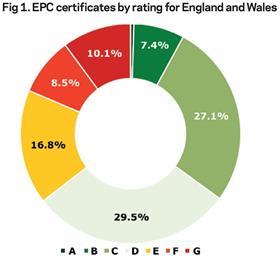

Almost 19% (~75,000 certificates) of the analysed dataset are likely to fall below the minimum standard, see Figure 1. A further 17% (~65,000 certificates) are E-rated and would be directly affected either if the threshold is raised after 2018, or as the assessment process is reviewed. For properties failing to meet the minimum standard, landlords must identify cost effective measures to improve the energy performance of the property, until it is no longer below the minimum threshold.

Geographic distribution

The distribution of ratings in each of the 10 Government regions of England and Wales is broadly consistent indicating that there are “good” and “bad” units in every region. The number of certified units varies, with the largest number of certificates in London and the South-east and the lowest number in Wales and the North-east. In part, this variance reflects the differing levels of market sales and letting activity across the country.

London postcodes have high absolute numbers of E, F and G rated units and these also represent an above average proportion of the overall rated stock. This means that even in areas with high property values there are substantial numbers of buildings with poor energy performance ratings.

In part, this might reflect the age of many of the properties as other towns with a high proportion of E to G rated EPCs, such as Shrewsbury, Bath, and Harrogate, also have a significant number of historic buildings.

Distribution by property type

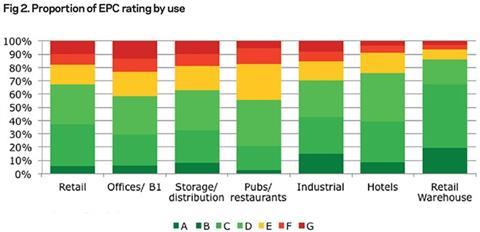

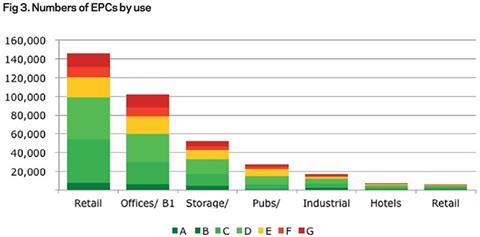

The office sector has the highest proportion of F and G certified units and a large proportion of Es (see Figure 2). However, in terms of total numbers of units (see Figure 3) the retail sector has more F and G certificates. For some sectors, including retail warehouses, hotels and industrial buildings, the sample size is relatively small. This may reflect not just the absolute size of the sectors, but also a lower volume of sales transactions and, in some cases, a high proportion of owner-occupied buildings, where fewer certificates have been triggered by lettings.

04 / Is it likely that the EPC rating will be improved through cyclical refurbishment or redevelopment before 1 April 2018?

An F or G EPC rating may be a symptom of age and approaching obsolescence, when it might be expected that redevelopment or refurbishment would improve energy efficiency as an inherent part of general improvements. The economics of refurbishment and the limited potential in many locations to add sufficient value through increased rents make it unlikely that, in the absence of a regulatory driver, substantial numbers of F or G rated properties will be improved through normal cyclical investment. The introduction of MEPS could speed up the refurbishment process as without this stimulus landlords are likely to continue to deferring major capital costs to the detriment of improved energy efficiency.

However, for some buildings, most notably retail where reletting is commonly accompanied by a new fit-out; the process of reletting is more likely to trigger work which would upgrade the EPC rating irrespective of a MEPS obligation.

05 / Can an F or G rating be improved to E or D through cost effective improvements?

The approach to improving a building’s energy rating and the extent to which this can be done cost effectively varies significantly for a wide range of factors. To understand the issues that might arise, 14 archetype buildings representing a range of asset types, conditions and specifications (see Table 2) were assessed and costed improvement strategies were developed.

Costing assumed that the investments were “out of cycle” i.e. the full cost of the works is considered rather than the marginal cost above works already planned.

Table 2: Archetype models

| Archetype | Sector | Servicing | Fabric / Glazing | Notes | EPC Rating | EPC Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Industrial - warehouse | Heating | Poor fabric / no insulation | Original services | G | 212 |

| 2 | Industrial - warehouse | Heating | 1990 Part L / limited insulation | Mid-range lighting | F | 137 |

| 3 | Industrial - warehouse | Heating | Late 90s / early 00s (insulated) | Poor lighting | F | 137 |

| 4 | Industrial - warehouse | Heating | 1990 Part L / limited insulation | Modern lighting | F | 134 |

| 5 | Retail - high street shop | Air con | Poor fabric / lighting | Original services | G | 162 |

| 6 | Retail - shopping centre unit | Air con | Poor fabric / lighting | Original services | G | 162 |

| 7 | Office | Heating | Poor insulation & glazing (1980s) | Original services | G | 171 |

| 8 | Office | Heating | Pre 1995 / double | Original services | E | 121 |

| 9 | Office | Air con | Poor insulation & glazing (1980s or before) | Original services | G | 209 |

| 10 | Office | Air con | Poor insulation & glazing (1980s or before) | Replaced services - post 2000 | G | 189 |

| 11 | Office | Air con | Pre 1995 / double | Original services | G | 157 |

| 12 | Office | Air con | 2002 / double | Original services | F | 148 |

| 13 | Office | Air con | 2006 / double | Original services | E | 120 |

| 14 | Office | Air con | Pre 1995 / double | Replaced services - post 2000 | F | 125 |

Modelling shows that it is possible to make substantial improvements in the energy efficiency of many of the archetypes delivering energy, carbon and operating cost savings. Cost effective improvements can also be made to some E rated archetypes as well as those with F or G ratings.

The naturally ventilated building archetypes could be improved to a D rating cost effectively. These works typically include new lighting, boilers, pumps, power factor correction and, in the case of some industrial units, enhanced insulation. Conversely, it is unlikely that air conditioned offices (particularly those that have been built to 1995 �ڶ����� Regulation standards or earlier) would be substantially improved by MEPS legislation directly, because cost effective measures are normally insufficient to improve these buildings’ ratings.

For some industrial properties (e.g. archetype 1), significant energy efficiency measures such as roof and wall insulation are shown to be cost effective because of the substantial modelled energy savings. In these cases the capital cost implications of the MEPS policy could be significant (see below).

06 / For properties that pass the Golden Rule test, is the cost of finance significant in relation to the rent?

For most of the studied building archetypes, the cost of meeting MEPS obligations is less than 12 months’ rent and in some cases considerably less.

However, for industrial archetypes 1 and 4 the cost of compliance could be equivalent to two to five years’ rent in locations with lower rents, e.g. where rents are ~£4.50 per ft2 or less. Where MEPS works equate to several years’ rent, this cost is likely to be a material consideration in discussions of rent levels and service charges. The occupier’s willingness to contribute to repayments will depend on market conditions and belief that the energy efficiency investments will result in a genuine reduction in their costs of occupation. In many cases the actual energy use may be so low that the cost savings in the hands of the tenant will be small.

In higher value locations (particularly within central London) rent levels are such that it is typically possible to improve the performance of more modern (i.e. post 2002) F or G rated offices to a D rating for the equivalent of less than six months’ rent. Even though such investments are not cost effective when based on energy savings, landlords may choose to make defensive expenditure to improve a building’s rating, as a means of safeguarding their liquidity and value.

However, older air-conditioned offices (archetypes 9 to 11) cannot be brought up to a D rating even in the highest value locations without expenditure equivalent to more than six months rental income. In these cases it might be expected that these properties would only be materially improved when subject to a full redevelopment / refurbishment process. These properties are therefore, in value terms, the most likely to be at risk from MEPS.

07 / Is the proportion of finance repayments met by the landlord during void periods high enough to undermine the viability of future lettings?

Landlords retain liability for repayments during void periods and this will reduce net landlord income over the life of the asset. In most cases the impact on rental income is small at 1.5-4% of income depending on property type, even in the locations with the lowest rents. However, for industrial archetype 1 in the lowest rent location and with high void levels, a landlord’s income might be reduced by 10-15%. This is equivalent to 12-18 months’ rent over the repayment period and could become a significant factor in future decision-making.

It is likely that the impact of voids on landlord liability will fall most significantly on low value properties that are already of marginal viability (given their current low rental value and long void periods). The reduction in rental income from MEPS may not be sufficient in isolation to affect a decision to continue to let a property. However, it may, in some circumstances tip the balance towards a decision to leave a property vacant or to demolish pending future redevelopment becoming viable.

08 / Conclusions

The minimum energy performance standard is widely expected to be an E rating. However there is both the possibility that this will increase in the future and that the methodology for assessment may be revised and become more stringent. Therefore, in addition to F and G rated properties, some rated E are likely to be affected adversely in terms of market value as they may be deemed “riskier” than better-rated buildings.

In all the modelled scenarios, it makes more economic and strategic management sense to spend enough to improve the EPC rating to D. Although the costs of so doing are generally higher, the associated measures would deliver significantly greater savings in energy, carbon and associated costs. It would also provide some “future-proofing” because, while it is not known if / when the minimum standard might be raised, undertaking work first to move to an E and then, later, to D will incur disruption, double overheads and be wasteful in terms of embodied carbon. For lighting in particular, improvements required to deliver an E rating might need to be stripped out and replaced again to achieve a D.

The distribution of ratings across the 10 government regions of England and Wales is broadly consistent, although a more fine-grained, postcode level, assessment reveals a much wider disparity of results. Generally, between 30 and 40% of properties are E, F or G rated but the greatest variance lies within, rather than between, postcodes, suggesting that impacts are likely to be seen at a very local level, irrespective of the overall level of affected property.

The research revealed that for many types of buildings tested, particularly naturally ventilated units, the requirements of MEPS will be cost/value effective and the requirements under the “Golden Rule” under the Green Deal will be met. Where this is the case, the measure should be absorbed by the market; however this may not be the case for older air conditioned units and some industrials. For the former, the level of obligated expenditure will be limited by the scale of cost effective efficiency measures. However, for some industrial units with a combination of low value and significant capital cost may mean that the costs and risks to income imposed by MEPS might reduce the number of buildings available for temporary lettings and accelerate the obsolescence of tertiary stock.

For some of these industrial buildings, the scale of potential investments (eg. insulation of roofing and walls) needed to comply with MEPS is significant. Therefore, it is important that compliance models are sufficiently sensitive to only require investments that will deliver savings in practice. There is little point in incurring significant costs (and embodied carbon) to insulate a building that is not occupied or used in the manner envisaged.

A clear statement from government regarding the future evolution of the MEPS policy and a proposed timescale for incremental changes would help owners plan for additional investment at an earlier stage, or as part of cyclical works, bringing forward the associated carbon savings and benefits for occupiers and reducing uncertainty.

Above all, rumours in the market place that all F and G rated buildings will need to be improved to at least an E-standard, regardless of cost and that unimproved buildings will be unlettable and therefore without value are inaccurate and largely unfounded. Compliance with the new regulations will be affordable for most property types and, in many circumstances, the existing value of F and G rated buildings will be largely unaffected.

No comments yet