Sweett Group looks at the costs of achieving different ratings under the BREEAM 2014 certification for new offices

01 / Introduction

Taking sustainability into account when designing and constructing new buildings is increasingly common practice in the UK, and requirements are now often set by clients in their project briefs.

Sustainability rating standards such as the BRE Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) are routinely used as a means of devising, achieving and demonstrating the sustainability credentials of buildings.

To investigate whether buildings with high sustainability standards actually cost more to develop than those that simply comply with �ڶ����� Regulations, the �ڶ����� Research Establishment (BRE) and Sweett Group developed indicative benchmarks for the costs associated with achieving different ratings under the BREEAM 2011 scheme. The study uses real project cost information to calculate the effect on capital costs of achieving Pass, Good, Very Good and Excellent ratings.

The study also considers the life cycle savings that might arise as a result of reduced energy and water use in these properties.

The full results of this research were recently published in the BRE publication Delivering Sustainable �ڶ�����s: Savings and Payback.

The launch of BREEAM 2014 has resulted in a series of changes to the assessment method and credit requirements. As new projects that have not been registered against previous BREEAM schemes will now be assessed against 2014 standard, it is important to consider the implications of these new requirements.

02 / A few important caveats

The costs and value of targeting any BREEAM standard will vary according to many factors, for example the baseline specification and design of the project will impact on the scale and nature of any costs associated with achieving specific BREEAM credits.

Only a small proportion of the more than 120 credits in the BREEAM 2011 scheme are suitable for generic monetary quantification of their benefits or payback.

Many of the most important benefits associated with achieving specific BREEAM standards are relatively intangible (for example, acoustic performance or daylighting)1 or address the wider externalities associated with the building and its construction and, by definition, do not directly result in savings to the developer or occupier.

Ultimately, the purpose of the development, be it a city centre office or a business park, will influence the approach to certification and the value obtained from targeting specific credit areas.

Some building occupiers are increasingly sophisticated and expect to see high BREEAM standards and are even influenced by the nature of the credits targeted (for example, expecting to see a focus on those that offer additional benefits to them).

In other situations there is relatively little occupier awareness of what building certifications generally signify and the only real driver is that a minimum planning expectation is achieved in the most cost effective manner.

Any form of cost benchmark, can only provide an indicative assessment of the likely costs that might occur on an individual project and should be treated as such.

Perhaps more importantly, the real costs of running a building, no matter how green a building’s credentials are on paper, are most heavily influenced by its commissioning, subsequent management and the behaviour of its occupiers.

1) Some exciting new work by the World Green �ڶ����� Council consolidates the evidence base on the health and productivity value of well designed and constructed buildings (Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices: The next chapter for green building, www.worldgbc.org).

03 / BREEAM 2011

While achieving lower BREEAM ratings, such as Pass and Good, incurs no (or very little) additional cost, these ratings are misnomers in that a Good certificate is perceived as anything but. Securing higher BREEAM ratings doesresult in some additional capital expenditure, but is likely to be less than 2% and in a “typical” location would be 1% or less.

The potential payback on these additional costs is only two-to-five years through utility cost savings2. However, for many developers the key to the business case is that without a suitable BREEAM rating the building might not be considered of ‘prime’ quality with associated impacts on rents and yields.

A very small reduction in yield (for example, from 5.1% to 5.0%) would be sufficient to significantly outweigh the costs of achieving an Excellent rating even on a difficult site.

This study is consistent with other research and contributes to a growing body of evidence showing that (where properly implemented) sustainability strategies add little to capital costs and that there is a life cycle and value case for ensuring high standards are achieved.

2) These operational savings and paybacks will only be realised if a building is constructed, commissioned and handed over to the end user in such a way that the ‘performance gap’ is minimised; i.e. that the building performs in practice closely to the design expectations.

04 / Changes between BREEAM 2011 and 2014

BREEAM 2014 is a refinement of the 2011 scheme, rather than a complete overhaul. Most of the changes are relatively minor “tweaks” to the previous guidance, to reflect improvements in industry practice and bring them in-line with current �ڶ����� Regulations.

However, there are some key changes in credit application and weightings, the scope of key credit areas together with the introduction of new credit criteria for different aspects of building design, construction and performance, which are worth further discussion.

Credit weighting and application

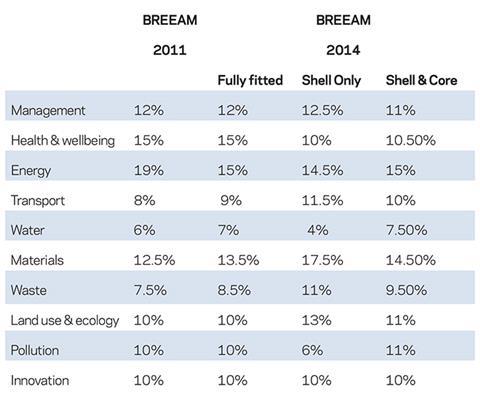

The first point to note is the change in relative weightings of the different credit categories.

The overall contribution of the Energy section has reduced from 19% to 15% with the relative value of credits in the Transport, Water, Materials and Waste categories each increasing by 1%.

A new development in 2014 is that the section weightings differ depending on whether the building is a Shell Only, Shell & Core or a Fully Fitted-out development.

The change in section weightings reduces the relative importance of Energy credits, and means that they contribute less to the overall score than previously. In addition to reduced overall contribution to the final rating, the approach to several of the key Energy related aspects of BREEAM changes in 2014.

It should also be noted that the previously available Green Lease and Green �ڶ����� Guide evidence options are not available for Shell Only and Shell & Core developments in the 2014 scheme. BREEAM New Construction 2014 must be used to assess Shell Only and Shell & Core developments, achieving BREEAM certification for works only up to that point.

If a fully fitted out BREEAM certification is required, then a separate additional assessment must be undertaken for the fit out works under the imminent BREEAM Non-Domestic Refurbishment and Fit Out scheme.

Ene 1

Called Reduction of emissions in BREEAM 2011; this credit area is now called Reduction of energy use and carbon emissions, revealing a key change in philosophy. The focus has now moved towards a “fabric first” approach, in line with the updated �ڶ����� Regulations Part L 2013, by calculating the score solely on the energy performance ratio (EPR) and removing the requirement for a percentage reduction in regulated CO2 emissions.

Ene 4

This credit area is now called Low carbon design, rather than Low and Zero Carbon (LZC) technologies. Credits for a percentage reduction in CO2 emissions have been removed, and new credits relating to consideration and implementation of passive design and free cooling strategies have been introduced. Again, this demonstrates a shift towards promoting a “fabric first” approach over and above the introduction of LZC’s.

Mat 6

A credit area has been in introduced called Material efficiency. Credits in this area aim to encourage project teams to “identify, investigate and implement measures to optimise material use at all stages of the project”. They are only required to implement those that are “appropriate” to a scheme and so the only definitive cost is that associated with the investigations within the project team.

Waste

Two credit areas have been introduced in the waste section: Wst 05 Adaptation to climate change and Wst 06 Functional adaptability. These have been created to promote design and construction of buildings that are resilient to climate change, and to encourage measures taken to accommodate changes of use over a building’s lifespan. Studies must be undertaken during the design process (during or prior to RIBA Stage 2) and implement findings where they are beneficial and cost effective.

05 / Implications of the changes in the 2014 standard

As stated, most of the changes between the 2011 and 2014 versions of BREEAM are evolutionary rather than revolutionary. However, it is valuable to assess whether the changes to the weightings, the scope of existing credit areas and the introduction of credit areas has a material impact on the sorts of costs that might be expected for achieving higher ratings. Analysis of an identical office specification using both the 2011 and 2014 scoring and reporting tools showed that an approach that would have achieved an Excellent rating (70.55%) against 2011 would achieve just under the Excellent threshold (68.60%) if assessed under 2014.

The key reasons for this are:

Ene 1

The outputs from the same BRUKL document were used to calculate the credits achieved. In 2011, the building achieved 10 out of 15 credits (2/3 of those available), contributing 7.04% to the overall score. In the 2014 assessment tool, the building again achieved 2/3 of the credits available (8 out of 12), but the score contribution was only 5.22%. Essentially, the performance of the building is deemed to be the same in the two BREEAM versions, as they both achieve 2/3 of the available credits. Therefore, there is no need to tighten the building specification in a 2014 assessment (as the “same” BREEAM performance is achieved anyway), so no additional capital expenditure should be incurred. The difference in score contribution results from the reduction in the category weighting, which is compensated by the increase in the weighting of other categories.

Ene 04

In BREEAM 2011, it is a minimum requirement for achieving an Excellent rating that a compliant LZC feasibility study is carried out. As such, complying with this issue in 2011 comes at a cost when targeting Excellent even if you do not go on to install any LZC technology (as LZC feasibility studies are not provided for free). This minimum standard has been removed from the 2014 version, so will not be incurred if LZC technology is not incorporated in to the design - although it is expected that an LZC feasibility study will be undertaken, and associated costs incurred, if LZC technologies are to be included. This is a potential cost reduction between the two scheme versions, as an Excellent rating is possible without the inclusion of LZC technology, albeit in practice many schemes will still need to undertake such studies in order to meet planning or �ڶ����� Regulations requirements.

06 / ‘New’ BREEAM issues; Mat 6, Wst 5 and Wst 6

As mentioned, targeting the same issues in 2014 as you would do in 2011 will not necessarily get you the same overall BREEAM rating. This is in part because of the introduction of new credit areas that have diluted the value of pre-existing credits.

It is therefore important to consider the potential cost and value of the new credit areas to determine whether a project team would be better placed pursuing the new credit areas or targeting additional credits in those pre-existing issues that might not have been sought previously.

It is likely that the additional cost of targeting these new credit areas will be small, if present at all. There is little obligation to undertake specific measures that will incur defined costs and any actions arising from the investigations would only be required where they are demonstrably “appropriate”, “feasible”, and or “cost effective”.

Further there is relatively little prescription in the approach to analysis in these new credit areas (unlike many areas of BREEAM where the steps are closely defined) and therefore the project team be able to tailor the analysis so that it is proportionate to the project’s value, risks and opportunities.

There will be some additional analytical time required to investigate each option however this is likely to be relatively small (albeit incrementally adding to the plethora of tests and analyses now required or any project) if programmed effectively and integrated into the design development process.

This necessary forethought shouldn’t be materially above and beyond the existing forethought required to design and construct a BREEAM Excellent office.

07 / Conclusions

For a typical office building, the changes to the BREEAM standard between the 2011 and 2014 versions should not materially change the capital cost implications.

The additional issues introduced in the 2014 standard should not compel the project to incur significant costs and may help to highlight cost saving or value enhancing opportunities. As such, climate change adaptation, functional adaptability and materials efficiency studies may well become more common parts of the project delivery process.

It is important, at this stage at least, that the approach to these studies remains flexible so that they can offer value to the project without burdening it with unnecessary additional administration

1 Readers' comment