Costing Steelwork is a series from BCSA, Steel for Life and Aecom that provides guidance on costing structural steelwork. This quarter provides a market update by Dr Michael Sansom based on recent CPA construction industry forecast publications, data on prices and costs from Aecom and an article on some of the changes in the updated FprEN 1993 Eurocode 3 ŌĆō Design of steel structures

Total UK construction output is forecast to have fallen by 2.9% in 2024. New construction activity fell by 4.3% in 2024, with repair and maintenance falling by 0.9%. A slowly improving UK economy is expected to yield construction growth of 2.1% in 2025 and 4% in 2026.

The economy returned to modest growth in 2024 supported by higher government spending and a recovery in consumer spending. UK economic growth is forecast to be 1.7% in 2025.

Public funded investment was disrupted by the general election in July 2024 and the subsequent review of existing government programmes. The spending review in spring will set out the Labour governmentŌĆÖs longer-term funding commitments and priorities, which are anticipated to include increased public sector activity.

The new government is expected to provide greater stability and certainty, and has signalled its intent to increase housebuilding and infrastructure investment during its five-year term.

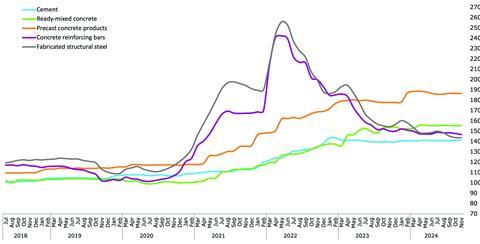

At the end of 2024, UK construction material prices were 1% lower than at the start of the year. The annual fall in the price of fabricated structural steel was 6.9%, whereas ready-mix concrete prices showed a rise of 4.3% over the same period.

The availability and cost of labour remains one of the greatest challenges facing UK construction. The demographics of the current workforce and delays to new infrastructure projects contributed to the fall in construction employment, which is estimated to have lost around 350,000 workers over the last five years. Annual apprenticeships starts are around 31,000 per year, but with a drop-out rate of around 40%. This is insufficient to replace the older workers leaving the sector.

In addition, the ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Safety Act (in particular the requirements at Gateway 2 of the approval process) appears to be leading to significant delays for ŌĆ£higher-riskŌĆØ building starts. Delays of up to six months have been reported by developers.

Figure 1: Material price trends

Price indices of construction materials 2015=100. Source: DBEIS

Year-on-year change in new construction activity in 2024 was sector-specific.

Infrastructure activity showed a decline in 2024 (-0.4%). Activity continues on major projects including HS2 and Hinkley Point, and long-term frameworks in the rail, energy and water sectors continue. The forecast for 2025 is growth of 1.4% resulting from the continuation of mega-projects together with offshore wind and related transmission projects.

The new governmentŌĆÖs renewed commitment to delivering net zero is also likely to accelerate investment in renewable energy generation and associated transmission infrastructure over the next few years.

In the commercial sector, refurbishment and fit-out of existing commercial buildings remains strong, as does activity on data centres and student accommodation. Overall commercial activity is forecast to have fallen by 2.8% in 2024. Looking ahead, investment in the UKŌĆÖs data infrastructure is likely to boost activity, as are changing hybrid working trends, but no sector growth is predicted for 2025.

Since the post-pandemic peak in 2022, the industrial sector saw a fall of 24.7% in 2023 and a more modest 4.7% fall in 2024. Low economic growth and higher interest rates impacted investment in speculative warehouse development, for which demand is expected to have passed its peak. This trend is expected to continue in 2025 with a further fall of around 3%. Forecast activity in the factory sub-sector is more positive, with large factories being built for EV battery production and wind turbine manufacture.

Tender price inflation strengthened in the final quarter of 2024, pushing up to 2.4% in the year. This has been due to the underlying reduced capacity in the industry leading to increased pressure when demand picks up. The building cost index rose by 3.7% in Q4, reflecting wage inflation and material price increases. The consumer price index kept below 2% for 2024; however, the increase in the energy price cap from January is likely to put further pressure on inflation.

Specification enhancements and regulation changes as a result of the carbon agenda and increased safety in buildings have had a significant impact on construction costs, which is a continued driver as the baseline of buildings has increased.

Figure 2: Tender price inflation, Aecom Tender Price Index, 2015=100

| Forecast* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Quarter |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

|

1 |

120.4 |

120.0 |

131.2 |

145.4 |

145.8 |

150.3 |

156.9 |

|

2 |

121.0 |

122.6 |

134.5 |

146.6 |

147.0 |

151.5 |

158.7 |

|

3 |

119.1 |

125.3 |

138.1 |

146.8 |

148.1 |

153.2 |

160.4 |

|

4 |

119.1 |

127.5 |

142.3 |

145.6 |

149.1 |

155.2 |

162.2 |

Sourcing cost information

Cost information is generally derived from a variety of sources, including similar projects, market testing and benchmarking. Due to the mix of source information it is important to establish relevance, which is paramount when comparing buildings in size, form and complexity.

Figure 3 represents the costs associated with the structural framing of a building, with a BCIS location factor of 100 expressed as a cost/m┬▓ on GIFA. The range of costs represents variances in the key cost drivers. If a buildingŌĆÖs frame cost sits outside these ranges, this should act as a prompt to interrogate the design and determine the contributing factors.

The location of a project is a key factor in price determination, and indices are available to enable the adjustment of cost data across different regions. The variances in these indices, such as the BCIS location factors (figure 3), highlight the existence of different market conditions in different regions.

To use the tables:

1. Identify which frame type most closely relates to the project under consideration

2. Select and add the floor type under consideration

3. Add fire protection as required.

For example, for a typical low-rise frame with a composite metal deck floor and 60 minutesŌĆÖ fire resistance, the overall frame rate (based on the average of each range) would be:

┬Ż170.50 + ┬Ż113.00 + ┬Ż33.50 = ┬Ż317.00

The rates should then be adjusted (if necessary) using the BCIS location factors appropriate to the location of the project.

Figure 3: Indicative cost ranges based on gross internal floor area

| TYPE | Base index 100 (┬Ż/m2) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

Frames |

||

|

Steel frame to low-rise building |

154-187 |

Steelwork design based on 55kg/m2 |

|

Steel frame to high-rise building |

259-292 |

Steelwork design based on 90kg/m2 |

|

Complex steel frame |

292-346 |

Steelwork design based on 110kg/m2 |

|

Floors |

||

|

Composite floors, metal decking and lightweight concrete topping |

88-138 |

Two-way spanning deck, typical 3m span with concrete topping up to 150mm |

|

Precast concrete composite floor with concrete topping |

135-189 |

Hollowcore precast concrete planks with structural concrete topping spanning between primary steel beams |

|

Fire protection |

||

|

Fire protection to steel columns and beams (60 minutes resistance) |

28-39 |

Factory applied intumescent coating |

|

Fire protection to steel columns and beams (90 minutes resistance) |

33-53 |

Factory applied intumescent coating |

|

Portal frames |

||

|

Large-span single-storey building with low eaves (6-8m) |

112-147 |

Steelwork design based on 35kg/m2 |

|

Large-span single-storey building with high eaves (10-13m) |

136-175 |

Steelwork design based on 45kg/m2 |

Figure 4: BCIS location factors, as at Q4 2023

| Location | BCIS Index | Location | BCIS Index |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Central London |

125 |

Nottingham |

101 |

|

Manchester |

103 |

Glasgow |

93 |

|

Birmingham |

98 |

Newcastle |

89 |

|

Liverpool |

98 |

Cardiff |

103 |

|

Leeds |

90 |

Dublin |

90* |

*Aecom index

Steel For Life sponsors

Updated European Standard

The updated FprEN 1993 Eurocode 3 ŌĆō Design of steel structures, which is due to be published in 2027, contains a range of changes, as detailed below

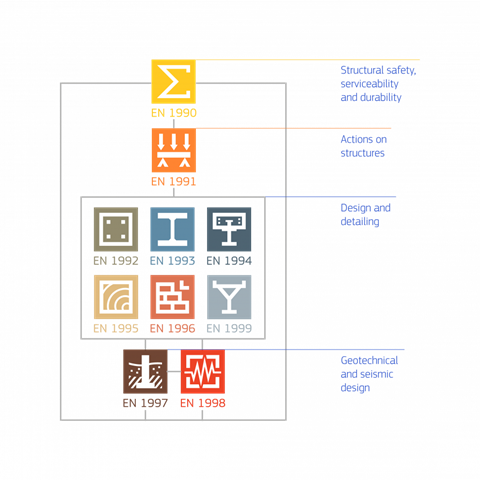

A European design standard, with country-specific annexes and design guides

Eurocode 3 provides both general and structure-specific recommendations for the design of steel structures that can be used by design engineers, fabricators and manufacturers to create safe, durable and sustainable steel structures. It was first published between 2002 and 2007 to enable the design of building and civil engineering works, and to determine the performance of structural construction products.

It has been adopted throughout Europe as the design standard for steel structures. It provides a common set of design rules to be used with a countryŌĆÖs National Annex. There have been significant advances in research, product performance and state-of-the-art practices, hence the review and updates which will be rolled out in the forthcoming years.

When will the second generation be published and mandated?

They are due to be published by the end of September 2027, with a period of coexistence where the first generation of Eurocodes are current and the second generation are available, but not implementable until the date of withdrawal in March 2028.

General changes in Eurocode 3

The most general changes to the second generation of Eurocode 3 are as follows:

- A revision of the table of contents, which means that designers will have to relearn where things are that they need to reference for design calculations.

- An extension of the scope to steel grades up to S700.

- EN 1993-1-12 will now include additional rules for steel grades up to S960.

- Clarification on the use of verbs to indicate how rigorously a clause should be applied by designers when using the recommendations given in the standards.

- There are two new parts. These are EN 1993-1-13, which gives rules for beams with large web openings, and EN 1993-1-14, which gives a common approach for the design of steel structures designed using finite element analysis.

Eurocodes at a glance:

Some of the most important specific changes:

EN 1993-1-1: Design of steel structures. Part 1-1 ŌĆō General rules and rules for buildings

EN 1993-1-1 deals with the structural design of individual components such as beams and columns, and the design of whole structures. It includes recommendations on the types of steel to be used and the material properties that should be used in design.

The revised version of EN 1993-1-1 includes an extension of the scope to allow steel grades up to S700 to be used. As a result, the ductility recommendations need to be revised to reflect the reduced ductility of higher-strength steels, particularly when considering the design resistance of a section with holes.

The revision also includes a new method for determining the lateral-torsional buckling of beams.

Other changes include: the design of elliptical hollow sections; the methods for structural analysis have been refined and summarised in a flowchart; a new method for the design of semi-compact sections (class 3); an improvement in the effects of torsion on the resistance of cross-sections and members; a simplified design approach for fatigue; and an annex providing statistical data of material and dimensional properties that were used for the calibration of the default partial factors.

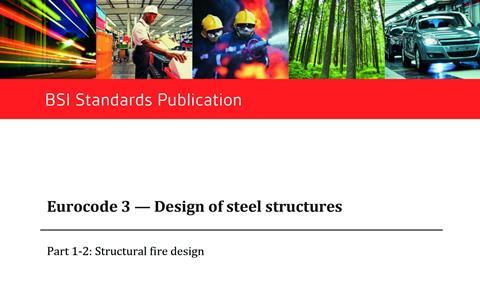

EN 1993-1-2: Design of steel structures. Part 1-2 ŌĆō Structural fire design

EN 1993-1-2 deals with the design of steel structures for the accidental situation of fire exposure with reference to the loadbearing function and only identifies differences from, or supplements to, normal temperature design. It is only concerned with passive forms of fire protection and also covers cold-formed members.

In revised EN 1993-1-2, nominal fires are applicable to steel grades up to and including S700. However, physically based thermal actions are only applicable to steel grades up to and including S500.

EN 1993-1-3: Design of steel structures. Part 1-3 ŌĆō Cold-formed sections and sheeting

EN 1993-1-3 deals with the design of cold-formed sections and sheeting.

The list of steel grades given in EN 1993-1-3 has been expanded.

Other changes include: rules added for the design of sinusoidal sheeting; the design of trapezoidal sheeting in axial compression; and the bending moment resistance of liner trays. There is also clarification on the design formulae for cross-sectional resistance of sections in combined axial force, bending moment, shear force and torsion and of the design provisions at serviceability limit states. Minor specifications and explanations have been added for the buckling design of sections in combined compression and bending. There are also new and special provisions for the design of trapezoidal sheeting with overlaps and special provisions for fasteners made of stainless steel in relation to corrosion environment deleted.

EN 1993-1-5: Design of steel structures. Part 1-5 ŌĆō Plated structural elements

EN 1993-1-5 gives design rules for stiffened or unstiffened steel plates that are subject to forces applied within the plane of the plate. It covers structural elements such as I-section girders, box sections and plated components used in tanks and silos.

The scope of the standard has been extended to cover non-rectangular panels.

Another change concerns the resistance of steel plate girders subjected to patch loading, with a new calculation for the reduction factor on the design resistance, recommended in clause 6.4(1).

EN 1993-1-8: Design of steel structures. Part 1-8 ŌĆō Joints

EN 1993-1-8 gives methods for the design of steel joints. This includes bolted joints, such as end plates, fin plates, and welded joints. It also covers tubular joints.

The revised standard has been extended to include the design of nominally pinned connections, with recommendations given in Annex C.

The standard also includes a new Annex D for the design of column bases with fasteners between steel and concrete.

Want to find out more about the changes to the second generation FprEN 1993 Eurocode 3 ŌĆō Design of steel structures?

The BCSA webinar on this subject, presented by Dr Ana Gir├Żo Coelho on 30 April from 12pm to 1pm.

The presentation will include details on the evolution of the Eurocodes, where they are now and what to expect in the second generation, and where we are at in the process ready for the withdrawal of the current Eurocodes in March 2028.

Dr Ana Gir├Żo Coelho will be giving a brief overview and also take questions and answers at the end of the presentation.

To register your attendance, click .

The Costing Steelwork article produced by Dr Michael Sansom (sustainability manager) of BCSA is available att . The pricing data and rates contained in this article have been produced by Patrick McNamara (director) of Aecom. They should be used for comparative purposes only and should not be used or relied upon for any other purpose without further discussion with Aecom. Aecom does not owe a duty of care to the reader or accept responsibility for any reliance on the article contents.

No comments yet