To commemorate its Diamond Jubilee, the Housing Design Awards revisited award-winning developments of the past 60 years, looking for those that, in particular, excelled as sustainable buildings. Martin Spring brings you the six winners. Photographs by Tim Crocker

The NHS and the Housing Design Awards elebrate their 60th anniversary this year. Not such an odd coincidence as it may seem. And thatŌĆÖs because both initiatives were launched in 1948 by Nye Bevan, who as well as being health secretary was also responsible for rehousing British after the war. BevanŌĆÖs enlightened rationale was that well designed housing would contribute to the nationŌĆÖs health.

Now in its 60th year, the NHS has undergone a radical review by Lord Darzi. For their part, the housing awards have been subjected to a retrospective review of all 3,500 winning housing developments since 1948. The intention of the organisers and judges of the Housing Design Awards was that the retrospective review would throw up a handful of all-time winners.

The first test the houses have to pass is simply to stand up to wear and tear and remaining fit for purpose (although not necessarily the original purpose).

The second test was that they had to be sustainable. The review of the award winners was co-ordinated by David Birkbeck, director of the Design for Homes agency. He says: ŌĆ£We threw out the ones that had problems, such as Roehampton Estate [in west London] and Washington New Town [in Tyne & Wear], which won dozens of awards between them. The housing in Washington was staggeringly awful in every way, with the worst possible detailing, materials and layouts. Stephen Mullin [who ran the awards scheme before Birkbeck] helped us by doing a health and safety audit on the schemes. He knew if anything had gone wrong with a scheme and the reason why.ŌĆØ

With advice from steering groups, architects and developers, the group drew up a shortlist of 15, which they went to visit. They then relayed their findings and photographs to the steering groups and ended up with six all-time sustainable award winners, which are shown on the following pages.

Sustainability was built into Bevan original plan for the awards. He said: ŌĆ£There is a temptation to cut standards, reduce size, eliminate planning and design,ŌĆØ he wrote. ŌĆ£But this would be a crime for which we, our children and grandchildren would pay for 50 years: it is a crime we must not commit.ŌĆØ

A vision such as that is as relevant to 2008 as it was to 1948. The six all-time award winners are published alongside this yearŌĆÖs crop in the Housing Design Awards booklet sponsored by the communities department, along with the NHBC, the RIBA and RTPI. In their introduction, the organisers evoke BevanŌĆÖs aspirations and write: ŌĆ£Here are six winning schemes, some of them little known, that exemplify the changing concerns of each decade, and the innovative thinking that designers brought to their resolution.

ŌĆ£They include developments that offered quality accommodation with an economy of construction, the first homes built to an environmental agenda, and a regeneration scheme that crystallises how chic architecture can see the reuse of once-proud buildings in an area of little value.ŌĆØ

At the same time, by proving their sustainability over several decades, the six all-time award winners are full of lessons on how to avoid committing that crime pinpointed by Bevan six decades ago.

1940s & 1950s

Post-war austerity turned to advantage

Highworth Cottages, Baughurst, Hampshire (award 1954)

Architect Powell & Moya, with Eric Chick

Developer Kingsclere & Whitchurch council

Contractor Percy Chick Builders

Highworth Cottages in rural Hampshire was designed by Powell & Moya in the aftermath of their more famous Churchill Gardens across the Thames from Battersea power station. But this modest scheme has proved even more influential, as it spawned a decade of ŌĆ£rational traditionalŌĆØ council housing across Britain in the sixties.

These were updated, highly economical terraced houses, with brick party walls either side and timber-framed facades and strip windows front and back.

Pat Lay (pictured) was one of the original tenants and still lives in the same house. She recalls how incredibly spacious it was when she and her husband moved in in 1953, and says it still performs as well as when it was built.

The assessors noted how the continuous glazing floods the rooms with daylight, and found the staircase ŌĆ£so fresh and elegant in its design it could have been built yesterdayŌĆØ.

For an ordinary house built within the constraints of post-war austerity, it was a remarkable achievement, they said.

1950s & 1960s

High-density urban village

Golden Lane Estate, City of London (awards 1961 and 1965)

Architect Chamberlin Powell & Bon

Developer City of London Corporation

Contractors G Wimpey & Co, Gee Walker Slater

Chamberlin Powell & BonŌĆÖs Golden Lane Estate was the precursor to their Barbican Estate next door and set the model for high-density urban villages, though it was rarely if ever emulated. On a blitz-flattened site, flats and maisonettes were packed in at the remarkably high density of 500 persons per hectare, along with a full spread of amenities, including swimming pool, tennis courts, shops, nursery, community centre and pub.

Many flats are still occupied by the original council tenants, while others have been snapped up by owner-occupiers, such as Paul Lincoln. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs a nice balance between the tower block and lower slab blocks, with communal gardens in between,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£So thereŌĆÖs no overlooking and it never feels crowded.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Inside, the flats and maisonettes have a clever internal layout and are incredibly well put together,ŌĆØ he continues, referring to the timber screen between the galley kitchen and the living space. He also picks out a walk-through sliding sash window, which opens on to a private balcony that leads down an external staircase to the communal garden. ŌĆ£My sash window still works after 50 years.ŌĆØ

1960s & 1970s

Community and privacy on a hillside

St Bernards, Croydon, south London (award 1971)

Architect Atelier 5

Housebuilder Wates

Following in the footsteps of Span Developments and architect Eric Lyons, south London housebuilder Wates aspired to lift spec housing to the level of luxury owner-developer villas. For St Bernards, Wates imported Swiss architect Atelier 5, who made inspired use of the sloping site, and balanced community and privacy at quite high density.

Three terraces of two-storey houses step down the hillside and are reached from the roadway by narrow walkways. On the upper floor, an entrance courtyard leads into the living rooms, which command spectacular views through floor-to-ceiling windows to communal gardens and the Surrey hills beyond. Tucked below that are the bedrooms next to a patio garden.

1970s & 1980s

Genuine neo-vernacular

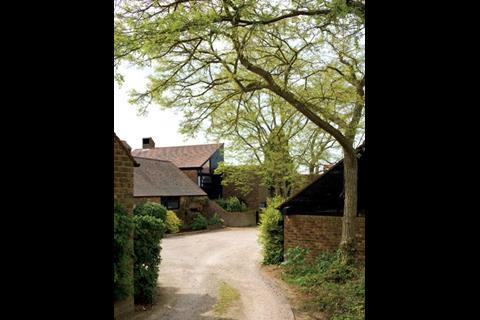

Lyde End, Bledlow, Buckinghamshire (award 1978)

Architect Aldington & Craig

Developer Lord Carrington

Contractor HJ & A Wright

Lyde End was built in the era of neo-vernacular housing of the seventies, but as it was developed by the former UK foreign secretary and designed by Peter Aldington, this scheme comes with the highest pedigree and is the antithesis of pastiche.

Nestled into the rural landscape are six mainly single-storey houses with monopitched roofs that interlock and cluster tightly around a communal courtyard. The construction includes clay tiles covering the roofs and load-bearing brick walls with small windows overlooking the courtyard. Away from the shared courtyard, larger windows and glazed doors open up the house interiors to their private gardens.

1980s & 1990s

Affordable and energy-saving

Spinney Gardens, Crystal Palace, south London (award 1987)

Architect PCKO

Developer Abbey Housing Association

Contractor Unit Construction

This housing scheme marries the now familiar concepts of affordable housing and energy conservation for the first time. It was developed by the Abbey National ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Society, which invited new concepts of low-energy design by opening up the design to competition.

The competition was won by four Polish architects, who came up with several passive solar-powered features that have lowered heating bills by 30%. These include triangular south-facing conservatories that soak up solar energy and similar triangular draft lobbies to the north-facing front doors.

ŌĆ£The conservatory is a good insideŌĆōoutside space thatŌĆÖs nice for sitting in and drying washing,ŌĆØ says resident Justin Kulaway. ŌĆ£I also like having balconies on both sides of my flat, one of them looking into the communal garden and the other looking out over the adjoining woods.ŌĆØ

1990s & 2000s

Urban regeneration through inspired design

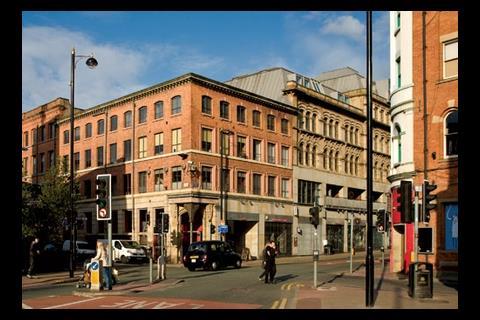

Smithfield ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°s, Manchester (award 1998)

Architect Stephenson Bell

Developer and contractor Urban Splash

Urban Splash has turned the property developersŌĆÖ mantra ŌĆ£location, location, locationŌĆØ on its head. The developer delights in buying derelict buildings in forlorn areas at bargain prices, and then bringing in top-flight architects and government grants to regenerate them as must-buy residences in must-live locations.

At Smithfield ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°s, the firm has led the way in bringing life back into Manchester city centre by converting the abandoned Victorian department store into flats above retail. Architect Stephenson Bell has dropped an atrium into the heart of the block and encircled it with galleries leading to the flats overlooking it.

Postscript

Original print headline 'Winning combinations'

No comments yet