Housebuilders are up in arms about councilsâ use of pre-commencement conditions, which they say are holding back schemes that have been granted planning permission

Housebuilders are - they say - in the grip of a paradox that is holding them back from their goal to get more houses built, and quickly. Reforms to the planning system that came into effect a year and a half ago have, as intended, resulted in more housing developments being granted permission more quickly and with greater predictability. And yet housebuilders complain that local authorities are still acting as a break on development. How come?

The blame is being laid on pre-commencement conditions - obligations that councils demand developers fulfil before they are able to start on site, covering everything from environmental strategies to the choice of roof tiles - which housebuilders and their representatives now claim are the biggest obstacle they face in increasing production.

Such conditions have existed for a long time, but housebuilders claim that in recent months councils have started to impose more and more complicated conditions, and that planning departments are obstructively tardy in

dealing with them. All of which means developers are left in a strange limbo where they have secured planning permission but find themselves unable to build anything.

But is the problem of excessive pre-commencement conditions really getting worse? And if it is blocking growth in housebuilding, what is to be done about it?

A growing problem?

Major housebuilders clearly feel frustrated by the way pre-commencement conditions are being imposed. But the issue has been on the radar for some time, and in fact pre-commencement conditions formed a substantial part of the 2008 Killian Pretty review, a report jointly chaired by former Barratt chief executive David Pretty and Essex council chief executive Joanna Killian. The review also made a series of recommendations regarding the conditions (see box overleaf). After the report, the issue has received little attention.

We have sites with more than 80 conditions and sometimes do not see them until the planning committee report. Frequently, too many conditions are imposed

Rob Perrins, Berkeley

But housebuilders have been very vocal of late. Earlier this month Bellway chief executive Ted Ayres singled out this issue in the commentary that accompanied his firmâs preliminary results, stating that the requirement to discharge numerous pre-commencement conditions is âadding unnecessary delay to the opening of new outlets to meet housing demandâ.

And speaking to șÚ¶ŽÉçÇű, directors at Linden Homes and Berkeley Group say that pre-commencement conditions are a huge, costly and in many instances time-wasting problem.

âWe have sites with more than 80 conditions and sometimes do not see them until the planning committee report,â says Rob Perrins, managing director at Berkeley. âFrequently too many conditions are imposed, which create work for the authority in having to discharge them, cost for the applicant, and delay the delivery of housing that everyone desperately needs.â

The charge is not just that conditions cause delays, it is that the problem is getting worse - and largely negating the improvements made to the planning process through the National Planning Policy Framework. â People probably arenât getting to site much quicker as a result,â says Roger Hepher, head of planning and regeneration at Savills. âI expect that if you did a proper analysis youâd find that there has been a small improvement, but it would be small.â

Speaking in September, Stewart Baseley, executive chairman of trade body the Home Builders Federation (HBF) said that he was âincreasingly concerned by the conditions attached to many permissions that prevent actual work starting on siteâ. And last month Steve Morgan told journalists and shareholders that one of Redrowâs current developments ended up having to deal with 109 separate pre-commencement conditions. An equivalent scheme built 20 years earlier, just across the road within the same local authority, had come with just nine conditions attached, he said.

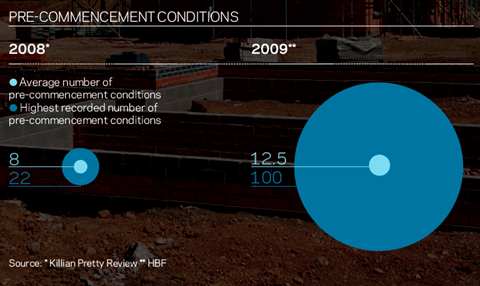

So, is the number of pre-commencement conditions imposed increasing? Finding evidence of this isnât easy as the data simply isnât collated at a national level. However, back in 2008, case study research for the Killian Pretty review found that on average, eight pre-commencement conditions were attached to each planning permission, and that there âcould be as many as 22â.

In a smaller recent and as-yet unpublished study, the HBF found that the average number of conditions had increased significantly. The study looked at 140 planning permissions for housing developments and found that the average number of pre-commencement conditions this » » year stood at 12.5 and identified instances of permissions coming with as many as 100. Many commentators well-placed to take a longer view also say that they have seen a long-term increase. âThe number of conditions on planning permissions has certainly crept up year on year for as long as I can remember,â says planning lawyer Simon Ricketts, a partner at SJ Berwin. âNow on any medium or large scheme there are a whole raft of conditions, many of them pre-commencement and requiring submission of all sorts of strategies and tranches of further detailed information, some of which is unnecessary.â

Planning pressures

So, why is the number of pre-commencement conditions increasing? Commentators cite the twin pressures that councils are under: cutbacks in planning departments and the pressure from central government to process planning applications at speed. âEverybodyâs under pressure to get through applications quickly,â says Savillsâ Hepher, arguing that difficult issues that would have been dealt with at the application stage are now pushed on and end up being dealt with as pre-commencement conditions. âItâs often tempting to say âwell, thereâs an issue here, but letâs not try to deal with it nowâ,â he says.

Hepher adds: âLocal authorities have cut back their resources - there arenât as many planning officers around to deal with these things - and it isnât particularly sexy work. My impression is that officers would rather be getting on with the next application than dealing with the tedium of sorting out the conditions on the last one.â

Pretty, on the other hand, doesnât lay the blame at the door of council planners; rather, he says that the increase is the inevitable upshot of the greater number of stakeholders whose views are sought on all significant applications.

Local authorities have cut back their resources - there arenât as many planning officers around to deal with these things - and it isnât particularly sexy work

Roger Hepher, Savills

âThe increasingly inclusive nature of the planning process compared to 20-30 years ago means that some conditions are being imposed following requests from third parties,â says Pretty, citing numerous national governmental and non-governmental bodies whose views are now sought on a statutory basis. âIf theyâre statutory consultees then they have a duty to make a recommendation. The more consultees you have on planning applications the more likely you are to get a long list of conditions.â

Hepher adds that the role of the planning system has gradually expanded over the years and is now legally obliged to consider a range of social and environmental issues that simply werenât within its statutory remit before. âIt goes back to this long-term trend of the reach of planning increasing year by year,â he says. âPlanning is used as a vehicle to achieve more and more socially desirable objectives.â

Unconditional

So what to do? Stephen Hill, secretary of the development management committee at the Planning Officers Society, acknowledges developersâ frustrations but says that in practice many of his members find that pre-commencement conditions are necessary because much of the detail hasnât been submitted at application stage. âApplicants are unwilling to risk the cost of providing such information ahead of securing planning permission,â Hill says. He adds that it is already considered best practice for planning officers to ensure that not all conditions need to be met before development begins.

However, some housebuilders are threatening to work outside of the system. âIn extreme circumstances, we would have to evaluate the risk and - so long as we werenât committing any offence - take a decision to carry on building,â says Graham Hutton, group technical director at Linden Homes. âIn such situations, we would have to indemnify purchasers, which would add to our costs.â

In extreme circumstances we would have to evaluate the risk and â so Long as we werenât committing an offence - take a decision to carry on building

Graham Hutton, Linden Homes

Hepher says that such strategies certainly happen, but that he always advises clients that they are taking a risk. âSome authorities are hotter on enforcement than others,â he says. âIn practice it rather depends on whether any member of the public or local councillor notices whatâs happening and makes an issue out of it. If things end up at appeal, planning inspectors are naturally reluctant to require perfectly serviceable buildings to be knocked down. In theory thatâs not [the way the system is meant to work], but in practice, given human nature, that tends to be how it works.â

SJ Berwinâs Ricketts agrees that there is a balance of risk to be weighed, but adds: âAny developer who carries out work in breach of condition has to do that with their eyes open because they could be liable for a breach of condition notice. Failure to comply is a criminal offence and they may end up not having a paper trail of approvals that would satisfy an end purchaser or funders.â

Far better than risking criminal prosecution, of course, would be if the system were made to work more efficiently. None of the housebuilders interviewed for this article wanted to see pre-commencement conditions scrapped. Rather they made suggestions remarkably similar to those contained in the 2008 Killian Pretty review: local authorities should think more deeply about which conditions genuinely needed to be met before construction can commence and understand more fully how their requirements impact on a developmentâs timetable.

Pretty is clear that he thinks the recommendations set out in his report are still applicable today. The coalition âmade very nice noises to me after they had taken power,â he says. But then nothing happened. âThey need to look at those recommendations carefully,â Pretty says. âI promise that they came not just from housebuilders but also from planning officers. I suspect that it hasnât been the highest of priorities, but they really need to dust off the review and look at those recommendations.â

And although there is some evidence to show that the burden imposed on housebuilders by pre-commencement conditions is getting worse, Pretty thinks the recent complaints may have more to do with improvements in the housing market than council recalcitrance. âItâs probably something that in the depths of the recession the housebuilders didnât worry too much about,â he says. âBut now that the market is starting to improve, everyone is looking to increase production.â And with an eye on the housebuildersâ and governmentâs shared goal of increasing the number of new homes, taking a close look at Prettyâs recommendations would seem a good place to start.

Recommended action on planning conditions: the Killian Pretty review

The Killian Pretty review stated that the government should comprehensively improve the approach to planning conditions to ensure that conditions are only imposed if justified, and that the processes for discharging

conditions are made clearer and faster by:

- Comprehensively updating national policy on conditions, including stronger guidance on the need to ensure conditions are necessary, relevant to planning, relevant to the development to be permitted, enforceable, precise and reasonable in all other respects

- Revising and updating national guidance on model conditions, including clear examples of where conditions should not be imposed, to avoid duplication with other statutory controls

- For major applications, requiring local planning authorities to provide applicants with draft conditions at least 10 days before a decision is expected and to consider responses from applicants before conditions are imposed

- Requiring local planning authorities to produce a structured decision notice, which groups the different types of condition into those that must be: discharged before commencement; discharged before occupation; or require action or monitoring after completion

- Requiring local planning authorities to place a copy of the decision notice and all conditions on their websites within two working days of formal planning permission being issued

- Develop workable proposals for speeding up the discharge of conditions involving - for example:

â The use of approved contractors to assist local planning authorities to discharge and monitor conditions

â The potential for a default approval of a condition, if not decided within a fixed time

â A fast-track appeal process for matters only concerned with the discharge of conditions.

No comments yet