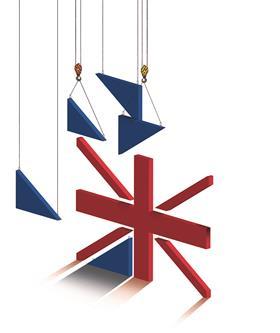

What effects would a âYesâ vote in the Scottish referendum have on the industry?

On 18 September Scotland goes to the polls in a momentous ballot to decide the future of the nation: should it remain part of the 300-year old union or opt for an independent future? And when it does, itâs a reasonable guess that the health of the construction industry will not be the issue at the forefront of voters minds.

But while the future of construction is unlikely to sway the vote, it doesnât mean that the choice made by the Scottish electorate wonât have far-reaching implications for the industry, both north and south of the border. From fundamental issues such as the viability of an independent Scotlandâs finances and its currency, to the health of its economy and concerns over increasing red tape for companies working on either side of the border, the prospect of independence raises huge questions - many that cannot be answered. And with Scottish first minister Alex Salmond putting in a strong performance in the live debate this week, there can be no surety of a âNoâ victory. Those supporting the âYesâ campaign point to the success of small independent economies such as Norway as models of how the economy could thrive when freed from the dead hand of Whitehall.

Scotland accounts for just under one out of every 10 pounds spent on construction in the UK, but until this week few in the business world have been clear about the where they stand - on one side or the other. So is there a case for independence, or are the fears about what it might do to the nationâs construction industry justified?

Personal or political

Kenny Anderson, managing director of ÂŁ7m-turnover Aberdeen-based contractor Anderson Construction and a former CIOB Scotland chairman, is a signed up member of the âYesâ campaign. He says an independent Scotland would create big opportunities for his business and the wider construction sector, by giving the industry easy access to and greater influence over the ministers deciding policy in Holyrood. He gives the example of campaigns to reduce VAT on refurbishment, viewed sympathetically in Edinburgh, which he says could have helped the industry in the recession but were vetoed by the Treasury in Whitehall.

âItâs about access to ministers who have full powers to help. With a country of 5.5 million people it is a lot easier to influence things.â Fears over issues such as the currency and EU membership, he says, are either overplayed or entirely confected by âNoâ campaigners. âWeâd see huge opportunities from it,â he says.

For many in construction the issue is an emotional or political one primarily. Chris Liddle, chair of Anglo-Scottish architect HLM, is the son of an English mother and Scottish father. âMy personal views are pretty mixed. I feel like one way or another Iâve been dealing with this issue most of my adult life,â he says. But despite this, in business terms he is optimistic either way. âHLM has been in Glasgow for 50 years, and weâre committed to this market whatever way the vote goes. Whether yes or no weâll continue to be a significant employer in Scotland. Iâm not sure itâs going to make a great deal of difference.â

In fact this view - that business is agnostic about the vote - is pretty much the orthodoxy, at least from those few who are willing to talk about the vote in public. As one housebuilder chief executive - who declined to be named - said, âwe will play the ball where it lies.â This view holds that the constitutional make-up of the UK doesnât affect the day-to-day activities of the industry, and any changes post independence will be dealt with in the same way as any other policy changes in the normal course of business.

This position does have a strong logic to it. Under devolved powers, the Scottish government already has control over building regulations, planning, and much capital spending. It is in the midst of reforming property taxation with a review of stamp duty, and Holyroodâs construction policies are a near mirror of those in Westminster. According to the CBI, 60% of spending is already devolved, something which has allowed the Scottish government to spend three times the amount on economic development, twice the sum on housing and 50% more on transport per person than is spent south of the border. And with the Scottish National Party promising sound finances and a 3% cut in corporation tax to mitigate fears of corporate flight from Scotland, it is easy to make a case that little will actually change.

Stephen Ratcliffe, director of the UK Contractorsâ Group, says: âThings are already different north of the border, the Scottish government has got a clearer pipeline of work, for example. Whatever happens [in the vote] there will be more devolution, so our members are not greatly concerned.â

Scotland has always been to some extent a separate market. By and large much of the work done in Scotland is by Scotland-based firms, with the main UK contractors that work there - Balfour Beatty, Morgan Sindall and Galliford Try - making efforts that their divisions there appear to their customers to be as âScottishâ as possible. One contractor chief executive, who declined to be named, says: âYou have to have Scottish people running your business if you want to win work in Scotland, as there is already a sense of a pretty high level of protectionism against contractors from the rest of the UK.â This view is backed up by a London-based architect working in Edinburgh, who also declined to be named. The architect said: âWinning work there you get very strong questioning along the lines of âwhy on earth should we appoint an English architect?ââ

Therefore fears that, post independence, the volume of cross-border working will be hit by a new protectionism, will be over-stated.

Climate of fear

However, the difficulty with this sanguine view of Scottish independence is that itâs hard to know how genuine it is. This weekâs letter by 132 business leaders to The Scotsman, backed by construction firms including Babcock and Morris & Spottiswood making the ânoâ case, was one of the very first such interventions. Businesses by nature loathe to speak out on such an emotive issue for fear of upsetting potential customers. On top of this are repeated media reports, echoed by a number of people spoken to by șÚ¶ŽÉçÇű magazine, of vague threats and intimidation against those that do speak out, made, supposedly, by some âYesâ campaign supporters, who imply they will be disadvantaged in winning work. Robin Nicholson, partner at architect Edward Cullinan, says he has spoken to some who have received this treatment. âI understand you get the call asking you to retract any statement youâve made questioning independence.â

âNoâ campaign supporter Anthony Rush, the retired former Tarmac Scottish MD and Barr Construction chairman, backs this version of events. âQuite frankly Iâve no doubt that this happens. For smaller companies the fear is that they wonât get an opportunity to bid for the next tender.â

The Scottish government and âYesâ campaign have denied in the strongest terms being responsible for any such activity, but whether the threats are real or not, the polarised climate makes it difficult for firms to raise concerns in public. For businesses with ambitions to work in Scotland, it simply doesnât make commercial sense to nail your colours to the mast.

Rush, however, is unafraid to speak out. He worked in the construction industry in Scotland for 30 years and sees himself as a sort of father to the Scottish building sector. A vigorous ânoâ campaigner, he has a variety of concerns, principally around the impact of a âyesâ vote on the Scottish economy and the state of the new countryâs public finances. âI canât see why the construction industry would benefit from it in any way. Thereâs nothing that says you should invest in [an independent] Scotland. If I was still at Tarmac going to the board to try and get investment in Scotland, Iâd be walking away with my head in my hands.â

Rushâs fears centre on the currency dilemma, and an independent Scotlandâs likely reliance upon wildly volatile revenues from North Sea oil. Tax revenue from North Sea oil, which was ÂŁ5.6bn in 2012/13, has made up anything between 10% and 21% of pro-forma Scottish government revenues in the last five years, with the figure twice collapsing by around 50% (see box, right) from one year to the next in that period. This volatility would make Scotlandâs finances very difficult to predict, whoever you believe in the heated debate about the general trajectory of future North Sea oil reserves. In contrast oil revenues make up just 1%-2% of the whole of the UKâs tax take, making the variability much easier to deal with at that level.

First minister Alex Salmond says this would be addressed by setting up a stabilisation fund, but the Confederation of British Industry says âshould revenues in an independent Scotland come in lower than expected, [it] would be forced to re-evaluate its spending choices in order to arrest the development of a significant fiscal gap.â

Balancing the books

Public spending per head is already 12% higher in Scotland than in the UK as a whole at ÂŁ12,300 in 2012/13, 23% more than the tax revenue it collects. For the UK as a whole this disparity between spending and revenue is smaller, at 19.5%, leading the CBI to conclude âScotlandâs overall outlook is worse than the UKâsâ in terms of public finances, with its deficit predicted to widen to 4.8% of GDP upon independence in 2016. The business lobby group also suggests Scotlandâs cost of borrowing would rise, with both issues together meaning it âis likely Scotland may even have to consolidate its fiscal policy on an accelerated timetable relative to the rest of the UKâ. To critics such as Rush all this implies a period of massive public spending retrenchment.

At the same time there are concerns that Scotlandâs financial services industry - a big success story till now - will be severely affected by uncertainty over the currency and the divergence of future regulation from the rest of the UK. Edinburgh-based RBS is one of a number to have flagged the uncertainties over independence as a material risk to the business in its company accounts, saying independence could âsignificantly impactâ the groupâs credit ratings, costs and have a âmaterial impactâ upon its prospects. Rush says: âThere is more than a risk that [financial services] companies will fly from Scotland and the economy will go into deep recession.â If he was still chair at Barr, he says, he thinks he too would be forced to flag it as a contingent liability in the firmâs accounts.

Rush says Salmondâs promise on corporation tax reductions are offset by promises to clamp down on tax avoidance. âAs theyâre promising to be tougher on forcing firms to pay up it doesnât seem to me the corporation tax question is a simple one for firms. Itâs not clear it will make it attractive enough to stay,â says Rush.

The rest of the UK accounts for 59% of Scottish exports. Mike Peasland, the Scottish former UK construction services boss for Balfour Beatty, speaking in a personal capacity, says: âFor a lot of our clients in Scotland the link with London was very important. These firms - Scottish Widows, Standard Life, RBS - they have been the mainstay of the Scottish building industry, either by funding it or doing it themselves, and they might be moving their base. Independence will not be good for Scottish construction and it will hit inward investment. Thereâs a big downside risk, but I canât see what benefit we might get.â

One listed UK contractor chief executive says the presumed combination of poor public finances and private sector retrenchment is particularly worrying. âIâm hoping itâs not going to happen,â he says. âThere will be a smaller construction industry in Scotland for 10 years if it does. Until now Scotland has been relatively spoilt compared with other parts of the UK in order to head off this debate. But a new independent government will have to make savings and the easiest way to do it will be cutting capital projects. I canât help thinking if we got a âyesâ Iâd have to start looking at downsizing.â

Asked what he would do if back at Balfour Beatty, Peasland says: âYouâd have be making some plans about what the future size of the business is going to be. You may have to re-scale the business.â

Gerry OâBrien, a Scot who is a partner at engineer AKT II, based in London, says: âI worry that it will have a much more negative impact in the long term than people realise. Norway is often held up as an exemplar of what could be achieved, but there is always the potential for it to produce a very significant downside. There may be closer parallels with the path of Ireland.â

Alongside these big economic and public spending questions, there are also concerns that making Scotland an independent country will add big costs to doing business, with currency transaction costs possible if it is prevented from adopting the pound, and diverging employment law and tax regimes. The CBI estimates currency transactions costs upon businesses would top ÂŁ500m a year; though Salmond insists an independent Scotland would use the pound even if the UK refused to form a currency union with it, despite the fact it would have to sacrifice control of monetary policy.

Rush says UK businesses could be landed with an additional cost of employing people in what will be a foreign country. âWe always have to pay people more to work abroad, to compensate for exchange rates, cost of living and inconvenience. This would be an issue.â Likewise, HLMâs Liddle admits divergent employment law could hit big firms. âAs a professional services firm weâd just deal with it, but if youâre employing 1,000 in Scotland then this is a very serious issue,â he says.

The final issue is that though only Scottish residents over 16 get the vote, independence would of course impact upon the rest of the UK. And not just constitutionally. Paul Brundage, senior managing director of Canadian property investor Oxford Properties, which counts the Cheesegrater as one of its projects, has experience of the negative impact of the Quebec independence debate of the 1970s and 1990s upon the wider Canadian economy. âIt created massive investor uncertainty and the Canadian dollar fell sharply. It took a long time to recover.

âIf this vote is remotely close then there will be a significant level of uncertainty over the outlook for the UK economy. Global capital is very mobile and absolutely, yes, people will be put off investing in the UK or in London because of this. If thereâs a shock to the economy because of this then we will have to be really thoughtful about the amount of capital we want to invest. This is a British issue, not just a Scottish one.â

So while the decision wonât be taken based upon the construction sector, the effects of the vote could be profound. Whether most of the industry is willing to say so in public or not.

Focus on the Scottish economy

As a Scot myself, when I am asked about the impact that Scottish independence could have on the UK economy and the construction sector I am reminded of that Donald Rumsfeld quote: âthere are known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknownsâ. It is a myriad of conjecture and opaqueness. Independence would be a large step into the unknown for Scotland and the remainder of the UK.

From an economic perspective the pro-union arguments centre on shared assets and risks, with the nationalists focused on maximising an independent Scotlandâs potential underpinned by oil reserves.

The main issue initially is the question of which currency an independent Scotland would use as this would define the trading environment that it would operate in. The SNP favour a formal currency union with the UK, claiming that it is in the interests of both parties to minimise transactions costs between the two. The Treasury claims that the problems with the eurozone currency union and likely divergence of the two economies make this plan unworkable. Once again take your pick on who you believe.

Right now Scotland accounts for about 10% of the value of contracts awarded in the industry over the last 12 months, the third biggest region behind only London and the South-east. In the same period Scotland has the highest share of infrastructure and education contracts by value in the entire UK. This indicates the differing nature of the Scottish market with a higher instance of public sector investment. Given that the aim of an independent Scotland is to increase public expenditure it suggests that this market would increase even further.

However, that all depends on how successful an independent Scotland would be at achieving a consistent budget surplus and therefore having funds available for investment in large infrastructure schemes. Based on the most recent figures from the Scottish government it would certainly seem that, at least initially, a consistent budget surplus would be hard to achieve at the outset.

Throw in uncertainty over currency and you are left with some interesting times ahead for an independent Scotlandâs construction market.

Michael Dall, Barbour ABI economist

| Importance of North Sea oil revenue to Scottish public finances | 2008/9 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | 2011/12 | 2012/13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scottish North Sea tax revenue (assumed geographical split) (ÂŁm) | 11577 | 5679 | 7454 | 10000 | 5581 |

| Total Scottish govt revenue (geographical split) (ÂŁm) | 55349 | 47733 | 51773 | 56315 | 53147 |

| % of total Scottish govt revenue made up of North Sea Oil | 20.9% | 11.9% | 14.4% | 17.8% | 10.5% |

| Total UK North Sea revenue (ÂŁm) | 12456 | 5991 | 8406 | 11336 | 6632 |

| Total UK govt revenue (ÂŁm) | 536271 | 516109 | 555506 | 576933 | 586925 |

| % of total UK govt revenue made up of North Sea Oil | 2.3% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 1.1% |

What does the SNP say on construction?

The âYesâ campaignâs 649-page âScotlandâs Futureâ document, setting out the benefits of secession, contains just five mentions of the word construction: twice in relation to prospects at the Faslane naval base where Trident is based, once in relation to Scotlandâs heritage sector, once in relation to building new power stations, and once in a graph to show the breakdown of Scotlandâs economy. It contains no overall vision for the sector. However, it does promise a supportive and dynamic business environment with corporation tax at 3% below the UK level, and investment in social housing, particularly by allowing councils more freedom to borrow to build. It commits to reducing carbon emissions more quickly than the rest of the UK, and pledges to quickly expand renewable energy generation capacity.

1. Currency union

The UK government and main opposition parties have all said they would decline to form a currency union based on Sterling with an independent Scotland. The nationalists say this is a bluff and have threatened to leave the UK liable for Scottish debts if the UK refuses. In any event they say they would use Sterling without an agreed union with the UK, despite the loss of control of monetary policy.

2. Scotlandâs public finances

To a large extent the state of Scottish public finances, and hence the extent of future spending, will be dependent upon tax revenues from North Sea oil, which account for up to 20% of tax take. Predictions for this are subject to debate, but all agree revenues will decline in the long term as reserves dwindle.

3. EU membership

An independent Scotland will seek to remain a member of the EU, with access to the common market a central plank of the SNPâs economic plan. However there is debate about how easy it will be to secure entry to the EU, whether the terms of entry will be as advantageous as those for the UK, and whether Scotland may be required to join the euro The time frame for agreeing membership is unknown.

4. Business regulation

An independent Scotland would see separate tax, employment and energy regulation regimes from the rest of the UK for the first time. The CBI suggests this could reduce labour mobility, load âmarkedly highâ tax administration costs upon businesses, and reduce effective subsidies for Scottish renewable power schemes.

Source

1 Readers' comment