With little prospect of a rapid reduction in interest rates to spur a recovery, many in the industry are now just looking to ‚Äúsurvive until ‚Äô25‚ÄĚ. Joey Gardiner looks at the prospects for residential developers doing so and explains why the affordable housing and build-to-rent sectors are unlikely to be able to ride to the rescue

There is a phrase you hear a lot in the residential development sector right now, with firms hunkering down to face a grim winter in the industry. No one quite knows who first said ‚Äúsurvive until ‚Äô25‚ÄĚ, but the meaning is plain enough.

However, even that bleak, Hobbesian slogan does not quite express how much of a slog the sector is in for, given many do not expect a strong recovery until much later than that. Bob Weston, founder of ¬£240m turnover Essex-based builder Weston Homes says his version is: ‚ÄúSurvive until ‚Äô25, and revive in ‚Äô27 ‚Äď There‚Äôs nothing round the corner.‚ÄĚ

Far from improving in the past six months, he believes that market conditions have only got worse. ‚ÄúI don‚Äôt think anyone in government knows or ‚Äď dare I say ‚Äď cares, how vulnerable SME builders, indeed anyone ranked below the top 20 biggest, are at this point.‚ÄĚ

Outside observers might be tempted to ask why on earth conditions for residential development are so bad. After all, aren’t mortgage rates coming down from their peak? And, with the Halifax and Nationwide both reporting house price rises in October, isn’t the housing market beginning to turn the corner of the cycle without having gone through the huge price falls that had been predicted? Aren’t we just starting slowly and steadily back down the road towards normal market conditions?

Alas, the assessment of most in the sector is that, while house prices are not likely to fall dramatically further, for residential development the downturn has only really just started. With interest rates likely to remain at their current level for some time, most experts and senior players in the sector believe only sustained return to low mortgage rates will bring about a rapid recovery ‚Äď something that the Bank of England has said is not going to happen soon. For the sector, this spells significant trouble.

Weak demand

It won’t be news to anyone to point out that weak buyer demand driven by high mortgage rates is at the root of the gloom engulfing the sector. Mortgage rates first spiked after the disastrous mini-Budget last autumn, then climbed again this spring amid persistent inflation.

Weekly sales rates at some of the builders fell in the summer months nearly as low as seen in the aftermath of the Truss-Kwarteng ‚Äúfiscal event‚ÄĚ last autumn, sparking lay-offs at Bellway and Redrow and a raft of distinctly depressing statements from listed builders regarding the outlook ahead.

The assessment of most in the sector is that while house prices not likely to fall dramatically further; for residential development, the downturn has only really just started

Barratt is to , Bellway is of a third and ‚Äď to give just three examples. Aynsley Lammin, equity analyst at Investec, says trading conditions for housebuilders have been the ‚Äúworst since the global financial crisis‚ÄĚ, and he expects volume from the industry to fall by 25-30% this year.

Developers are, of course, not just facing weak sales demand, they have also seen the closure of the Help to Buy support scheme for first-time buyers, experienced huge build cost inflation, and still face major obstacles in the shape of lengthening planning delays, the nutrient neutrality crisis and new ‚Äúsecond staircase‚ÄĚ regulations on high-rise blocks. All of which are having a direct impact on volume.

Andy Hill, group chief executive of South-east based housebuilder and partnerships provider Hill Group, says his firm‚Äôs private business is on course to sell just 75% of what he budgeted for this year. ‚ÄúWe‚Äôre now planning for slower sales rates,‚ÄĚ he says, adding that, in the wider market, ‚Äúhousing numbers are way, way down‚ÄĚ.

Market expectations around Bank of England interest rates are crucial to setting the cost of borrowing for homebuyers and, while mortgage costs have been declining slowly since June, there is now a growing consensus that rates will not return to the lows seen prior to the summer of 2022 in the medium term. The report accompanying the Bank of England‚Äôs latest rate-setting meeting made clear that it currently expects the base rate to remain above 4% until the start of 2027 ‚Äď meaning mortgage rates, which were commonly under 2% until last summer, will be significantly higher than that.

In the same report, it said the Bank estimated that housing investment ‚Äď largely made up of new-build spend ‚Äď had fallen by 6.4% in the year to Q2 2023, and was projected to fall by a further 9.4% by the end of 2026. ‚ÄúIt is much too early to be thinking about rate cuts,‚ÄĚ said Andrew Bailey, the Bank of England‚Äôs governor.

Given this, and despite the exhortations of some enthusiastic estate agents, few serious observers see any reason for a significant housing market recovery in 2024 (see market forecasts box), with most forecasters suggesting further modest falls. While observers say there is clearly ‚Äúlatent‚ÄĚ demand for homes, high interest rates prevent many mortgaged purchasers from being able to buy until prices fall further, while continuing strong employment, lender forbearance and a lack of forced sellers has stopped prices dropping as sharply as predicted.

The resultant stagnation means that, crucially for developers, all the forecasters expect transaction volume to drop significantly ‚Äď to around one million this year ‚Äď and only start to recover in 2025. The Construction Products Association (CPA) predicts a 20% collapse in industry output this year, with no recovery in 2024, and only marginal progress in 2025.

David Thomas, Barratt chief executive, says the Home Builders Federation‚Äôs recent prediction that, without government intervention, industry volumes could sink to as low as 120,000 a year in the coming years ‚Äúseems plausible‚ÄĚ.

Alex Bannister, an independent economist working as an adviser to housing data firm TwentyCI, says: ‚ÄúIt doesn‚Äôt feel like there are the economic conditions for a further massive fall in prices, but likewise nothing is driving the market forward. We‚Äôre stuck with rates as they are. I can‚Äôt really see how this impasse unlocks right now.‚ÄĚ

Cutting the muscle

Many housebuilders have already responded by cutting some jobs either by direct redundancies ‚Äď as in Bellway‚Äôs decision to cut 5% of staff or by lengthy hiring freezes such as have been in place at Barratt, Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey, which are having much the same effect. Persimmon, for example, this week said its hiring freeze will result in a 700-person reduction in headcount by the end of the year.

Market forecasts

House prices

Forecasters have been surprised at how modest the price falls have been in this downturn so far, and now largely predict the market will escape without a significant price correction. However, this isn’t all good news: the slow fall in prices means that the recovery, which previously was predicted to have started by now, is now seen as being much further off.

Online listings site Zoopla/Hometrack is predicting 2% price falls this year and next year while estate agents Savills and JLL are both somewhat more gloomy, predicting falls of 4% and 6% this year respectively. Both forecast further falls of 3% in 2024. Savills and JLL both predict a return to house price growth in 2025.

Transactions

Following a spike in housing market activity during the covid period, the number of house sales hit 1.5m in 2021, comfortably the highest since the global financial crisis, falling to just over 1.3m last year. This year forecasters across the board suggest transactions ‚Äď which are closely correlated to new-build industry output ‚Äď will fall by around a quarter to one million, and stay flat next year.

JLL forecasts transactions could rise to as much as 1.2 million by 2025, while Savills remains cautious, putting it at just 1.04 million even in that year.

Output

The Construction Products Association has forecast that private new home starts will drop by 25% this year, to around 123,000, before recovering marginally in 2024 and 2025 ‚Äď albeit to a level well below 2022 starts. Completions are expected to drop 19% this year and stay flat next year at around 134,000.

The falls mean overall financial output in the new-build sector is expected to drop 18.5% this year, and register a further marginal fall in 2024, prior to a 3% recovery in 2024 which will leave the sector still over 16% below the 2022 output level.

However, builders at this stage appear reluctant to cut too deep in a desire to retain capacity for any recovery. ‚ÄúYou won‚Äôt see builders cutting into the muscle of the business right now,‚ÄĚ says Investec‚Äôs Lammin, ‚Äúbecause they‚Äôre expecting recovery on a two to three-year view. But, if in spring the market is still down, then you might see some real cutting into divisional overheads.‚ÄĚ

Neal Hudson, MD of research firm Resi Analyst, says it may come sooner than that: ‚ÄúI suspect we‚Äôll see more cuts over Christmas and into the new financial year. I think the housebuilders have been surprised that sales have been weaker than expected. People are nervous about what happens next.‚ÄĚ

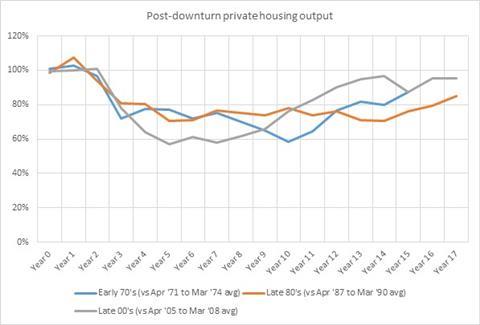

However, taking a short-term view on this issue could have long-term implications. An analysis (below) of housing completions from previous significant housing downturns shows that the industry on average takes over a decade to reach its pre-recession output ‚Äď an issue that will be compounded if vital skilled staff are lost.

‚ÄúBluntly, [industry] volumes will be impacted as long as the market weakness continues [as the] industry matches its build rates to its sales rates,‚ÄĚ Barratt‚Äôs David Thomas says. ‚ÄúThe wider issue however is how long it can take to recover if the industry downsizes, losing skills and capacity particularly in the sub-contractor trades that take a long time to recover.

‚ÄúLikewise, the industry has reduced the amount of land it is buying at the moment which will take time to ramp up and get through planning as demand increases.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúAbsolutely dreadful‚ÄĚ

The issue is not just confined to the private sale market. In previous downturns, governments have used affordable housing to provide a counter-cyclical stimulus for the development sector, but for a number of reasons that seems not to be on the agenda.

Prior to last year‚Äôs mini-Budget, social housing landlords were already facing ever-increasing demands to invest in their existing stock to tackle net zero, fire safety and damp and mould issues, amid uncertainty over their longer term rental incomes ‚Äď thereby limiting cash for new-build.

However, since the cost of capital shot up a year ago, associations now additionally need their development projects to provide much higher returns over 30 years in order to be declared viable ‚Äď or slugs of public money. Given this, far from increasing output to offset private sector weakness, many associations are sharply cutting back on their programmes.

Paul Hackett, chief executive of 78,000-home London-based association Southern Housing, says: ‚ÄúThe market is absolutely dreadful for housing associations at the moment. Everyone is seriously dialling down development.‚ÄĚ

Since the cost of capital shot up a year ago, associations now additionally need their development projects to provide much higher returns over 30 years in order to be declared viable

Hackett says Southern has increased its viability ‚Äúhurdle rates‚ÄĚ due to the increase in government gilt rates, such that the organisation‚Äôs annual development starts will drop from a recent peak of 2,000 to around 250 this year ‚Äď more than 80% down on the average over the last five years.

‚ÄúPreviously as a sector we were counter cyclical [to the private market],‚ÄĚ he says, adding that grant giving bodies Homes England and the Greater London Authority are engaging on a project-by-project basis to try to help individual schemes, but that this cannot help all projects.

‚ÄúThe problem is that, with the growth of the affordable rent product and the cross-subsidy model reliant on private sales, now the sector is increasingly pro-cyclical.‚ÄĚ

>> See also: Reforming planning: one way to solve the housing crisis

Demand for affordable housing ‚Äď including shared ownership ‚Äď remains incredibly strong and partnerships providers such as Vistry, which this week signed an ¬£819m forward-funding agreement with ‚Äúfor profit‚ÄĚ provider Leaf and Sage, have been having some success getting deals agreed, particularly when working in joint venture with housing associations.

However, given the challenges faced by associations, the more traditional Section 106 funding route, whereby housing associations buy the affordable housing allocation on private sites, is looking much more iffy.

Hill‚Äôs Andy Hill says the price paid by associations on s106 is about 10% down in the past year, while Richard Jones, partner at Arcadis, says ‚Äúdevelopers can‚Äôt get associations to bid for the affordable housing. It doesn‚Äôt come at the value they want.‚ÄĚ

Triple whammy

Hackett says that for established providers such as Southern the situation is a ‚Äútriple whammy‚ÄĚ affecting development, but that even the new breed of ‚Äúfor profit‚ÄĚ providers are struggling with viability given the cost of capital and future rental income uncertainty.

Earlier this year consultant Savills forecast the new breed of ‚Äúfor profit‚ÄĚ registered providers were on course to develop over 85,000 homes in the next five years, but Emily Williams, director of residential research at Savills, says the increasing rates are putting that in jeopardy. ‚ÄúAt the moment, until there are cuts to the base rate, it looks very hard to stack up these schemes.‚ÄĚ

Savills‚Äô Williams says the consultant is aware of 60 residential schemes of above 20 units currently on hold, and Hackett says the response from scheme promoters to the current viability situation is to ‚Äúpark up‚ÄĚ projects.

Anecdotally, the issue also looks to be affecting the build-to-rent sector in the same way. While demand for rented housing has rarely been stronger, the high cost of capital has given potential investors other ways they can make money.

Unsurprisingly, build-to-rent projects offering a 4.5% yield ‚Äď with all the attendant risks of development and construction ‚Äď are now not getting signed off when investors can buy a risk-free bond or gilt from the government offering a far better return.

Chris Jones, senior director leading on development consultancy at Arcadis, says that while there are opportunities where savvy investors and developers structure clever deals suited to the current environment, in general rising rates have hit viability ‚Äúhurdle rates‚ÄĚ for build-to-rent development.

‚ÄúWhere gilt yields have been closer to 5% and build-to-rent deals are around 4.25% it hasn‚Äôt make sense [to invest],‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúThis equation needs to flip, and allow for the risk inherent in residential development.‚ÄĚ

This dynamic explains why deal flow in the build-to-rent sector appears to have slowed since the Truss-Kwarteng Budget, despite booming rents. Noble Francis, economics director at the CPA, says: ‚ÄúUncertainty in yield, in finance costs and construction costs all mean build-to-rent is not now growing as quickly as it was.‚ÄĚ

Time to drop anchor

For Weston‚Äôs Bob Weston, looking for investor buyers for completed schemes, the reality on the ground is more stark still. ‚ÄúWe‚Äôve got quite a high level of stock. And there‚Äôs no one in the [corporate] market wanting to buy them, at whatever terms,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúSo, we‚Äôre having to drop anchor and stop building.‚ÄĚ

Many in the sector are looking to the government as the only real actor with the power to improve the situation ‚Äď but hopes are not high. Savills‚Äô Williams says the government should invest in an additional ‚Äúcomprehensive government funded affordable housing programme‚ÄĚ as the easiest thing to stimulate the market, while the CPA‚Äôs Noble Francis says the government should stimulate demand by paying to help first time buyers on to the housing ladder. However, Williams says a stimulus is not on the cards, and Francis says ‚Äúa new version of Help to Buy [‚Ķ] is increasingly looking unlikely.‚ÄĚ

Consequently, some are looking to political change at the forthcoming general election to provide some kind of market fillip ‚Äď even if it doesn‚Äôt provide an immediate positive policy change. Hill‚Äôs Andy Hill says he cautiously hopes there could be a post-election ‚Äúfeel-good factor‚ÄĚ, while Richard Donnell, executive director at Houseful, which owns Zoopla, says: ‚ÄúAs soon as interest rates fall, there is pent up demand. Maybe if you had a landslide election, timed with mortgage rates starting to fall ‚Äď then you might start to get some kind of bounce back.‚ÄĚ

In the meantime, the likes of Bob Weston are left pondering how best to make it through until that happens. ‚ÄúWe will survive of course,‚ÄĚ he says. ‚ÄúBut will we end up half the size? It‚Äôs a realistic option.‚ÄĚ

No comments yet