Ben Flatman takes a look back over a remarkable reign as seen through some key architecture

The reign of Queen Elizabeth II has spanned a remarkable period of change in British history and constuction. She came to the throne at the age of 25 in 1952, when Britain was still experiencing rationing, and bombsites pockmarked the nationÔÇÖs great cities. Her first prime minister was Winston Churchill, a man born at the height of time of imperial pomp and steeped in a Victorian sense of BritainÔÇÖs right to rule over others.

Over the following decades, as its former colonies broke free, the nation would struggle to find a new role in the world. The years since ElizabethÔÇÖs ascendancy to the throne have been marked by periods of confidence and then crushing bouts of national self-doubt and nostalgic longing for empire. From Suez to EU membership and then Brexit, the UK has often appeared to be lurching from one extreme solution to another, with stability and a clear vision of the future hard to find.

The same might be said of British architecture, which has seen huge ideological and stylistic changes during ElizabethÔÇÖs reign. In 1952 architecture was stuck in a strange limbo, not entirely sure of what to make of the rapidly changing international context, or international modernism.

>> Also read: Industry pays tribute to Queen Elizabeth II, 1926-2022

Perhaps it was the Festival of Britain, which had taken place in the summer of 1951, that helped to transform popular perceptions of what architecture and design might be in the postwar era. Over the following decades a restrained neo-Georgian influenced style gave way to the strident modernism of the 1960s and 70s.

It is perhaps not unfair to say that too many of the architects of this period became hubristic, sometimes imagining themselves capable of reshaping society through glass and concrete. The architecture that resulted was very often alienating and anti-urban. This in turn induced a reaction ÔÇô postmodernism and its perhaps unintended legacy of a typology of identikit homes in a car-centric suburbia.

And although British architectureÔÇÖs reputation has been in the ascendancy since at least the early 1980s, it is curious how this has not fully translated into the widespread application of sound urbanism and good design. Many of our nationÔÇÖs towns and cities are tawdry places, scarred by a lot of bad postwar planning (and architecture) and now left hollowed out by consumer capitalism and an eviscerated public sector.

As the nation begins its period of mourning, we look at some of the most significant buildings to have marked this most extraordinary reign and period in British history.

1950s: Hunstanton School by Peter and Alison Smithson

Peter and Alison Smithson were the self-anointed leaders of the postwar British avant-garde. They led British architectural modernism away from its neo-Georgian tinged timidity, towards a more stridently confident and overtly internationalist embrace of modernity.

They won the competition to design Hunstanton School in Norfolk in May 1950. It was the first major competition for a new breed of school, the secondary modern, instituted by an education act at the end of the Second World War with no clear sense of what it should contain, or indeed teach.

By 1950 the urgent programme of primary schools for the ÔÇťbaby boomersÔÇŁ was under way, and attention was turning to the next stage of their education. Steel shortages meant that little was built before 1954, when Hunstanton was completed and immediately hit the headlines.

By the time the school was finished, the Smithsons had already moved on. The formalism of Wittkower and Mies had given way to the looser planning of their Golden Lane and Sheffield University competition entries, and the term ÔÇťnew brutalismÔÇŁ had been coined. But in Hunstanton the honesty of materials and construction central to brutalism was already apparent.

1960s: University of East Anglia by Denys Lasdun

The 1950s saw a huge rise in the number of students in higher education, but for many years successive governments resisted calls to fund new universities. Norwich had bid three times for a university before, in 1960, the government finally accepted a proposal supported by county and borough councils across East Anglia (hence the name).

The abiding image was set by its first buildings, the product of a visionary client, vice-chancellor Frank Thistlethwaite, and an exceptional architect, Denys Lasdun.

Thistlethwaite and Lasdun developed their ideas over the early part of 1962. ÔÇťIt quickly became clear that there was a true meeting of minds about the way the academic designs should be resolved in architectural terms,ÔÇŁ Thistlethwaite recorded.

Lasdun studied the site intensely, both from a helicopter and on foot. In 1984 he described the buildings as being ÔÇťconceived as architectural hills and valleys. From the air, they are like an outcrop of stone. From the ground, they hug the landscape, which is itself preserved by the planÔÇÖs compactness and remains distinct from the urbanity of the university.ÔÇŁ

The iconic ÔÇťzigguratÔÇŁ structures defined the image of a new era in British higher education, in which state-educated baby boomers felt empowered to build a new meritocratic utopia.

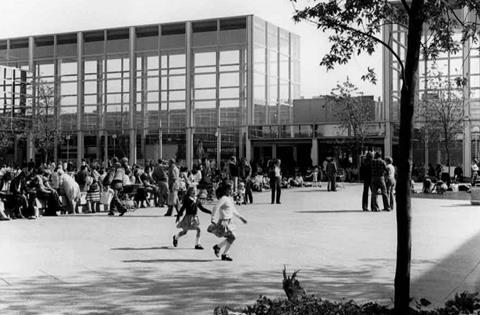

1970s: Central Milton Keynes shopping centre by Derek Walker

Milton Keynes represents perhaps the high-water mark of modernist urbanism in the UK. This most derided (and yet remarkably successful) of new towns, was founded in 1967.

Derek Walker was appointed chief architect in 1970 amid mounting frustration that virtually nothing had been built of the new town designated three years earlier.

Much is written about Milton KeynesÔÇÖs boulevards and roundabouts, variety of housing, the landscaping and the concrete cows, but relatively little about the strangest part of all ÔÇô a town centre almost entirely dependent on the car. Long boulevards are lined with low-rise blocks of offices, relieved by restaurants and fragmentary arcades, behind acres of parking.

All, that is, save the heartbeat shopping centre, designed in 1972-73 and built in 1975-79. It was finally listed in July 2010 after a long campaign by local pressure groups and the Twentieth Century Society.

1980s: Lloyds ║┌Â┤╔šă° by Richard Rogers and Partners

The 1980s saw the overthrow of the postwar consensus. Margaret Thatcher set out to crush the union movement and traditional working-class culture. Her government took a wrecking ball to ageing British industry and sought to replace factories with a financialised economy built around trading floors and unbridled consumption.

As the nation lurched between crushing recessions and reckless booms, architects struggled with a radically altered environment. In the 1970s, half of all architects had been employed in the public sector. The governmentÔÇÖs ban on council housing, and slashing of public investment, left many of them facing the dole queue.

But, amid the turmoil, a new generation was already pointing the way to a different form of practice. Richard Rogers had made a massive international impact with the Centre George Pompidou in Paris. In 1979 he won the commission to design a new home for the quintessentially City of London institution, Lloyds of London.

The resulting building is perhaps RogersÔÇÖ best work in the UK. It marks the embrace of a new reality for British architecture, as utopian ideals gave way to pragmatic commercialism.

1990s: the National Gallery Sainsbury Wing by Venturi Scott Brown

Modernism was clearly going through something of crisis from the late 1970s onwards. But architecture is a slow-moving art form and ideas and attitudes in architectural theory tend only to materialise in built form years later.

In the eyes of many critics the Sainsbury Wing was the built manifestation of a backward-looking right-wing ideology that had been led at the political level by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

In reality, it was the late flowering of the complex and subtle thinking that Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown had been developing together in their theoretical and built work for decades. Embracing history and the importance of symbolism in architecture, the Sainsbury WingÔÇÖs legacy is perhaps far more nuanced and positive than the hardcore modernists would ever admit.

Arguably, we are all postmodernists now.

2000s: Scottish Parliament by EMBT/RMJM

The 1997 landslide win by Tony BlairÔÇÖs New Labour ushered in a decade of relatively high public sector investment in architecture. It also saw a first significant move towards devolving power away from Westminster to the constituent nations of the UK (although England was overlooked and remains one of the most centralised countries in the world).

A referendum on Scottish devolution followed swiftly on the heels of the 1997 general election, with Scots voting overwhelmingly in favour of their own parliament.

The Scottish Parliament building, designed by EMBT with RMJM, opened in Edinburgh in 2004. Massively over budget, the building was widely ridiculed at the time. But it has come to be embraced by Scots. ItÔÇÖs semi-circular, light-filled debating chamber represents a clear desire to move away from the overtly confrontational politics of Westminster.

For some it is a sign of a mature devolved democracy, in which politicians make decisions as close as possible to the people that they represent. For others, it was a foolish mistake that has contributed to the unravelling of the union.

2010s: London Aquatics Centre by Zaha Hadid

When the Queen appeared to join James Bond in jumping out of a helicopter at the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games, Britain was giving every impression of being a country finally at ease with itself.

Zaha Hadid was born in Baghdad and had been drawn to the intellectual melting pot that was the Architectural Association in the 1970s. She won the Diploma Prize there in 1977 for her breath-taking and immediately recognisable drawings. But it would take decades for her to get the chance to build.

Sadly denied the opportunity to complete her Cardiff Opera House, Hadid found commissions and much-deserved success overseas. Only then did Britain start giving her work.

The London Aquatic Centre is perhaps not HadidÔÇÖs best work, but it is a striking reminder of more confident and happier times, when nation, architect and monarch seemed confidently able to assert that here was a modern country more comfortable with its place in the world.

2020s: Cambridge Central Mosque by Marks Barfield

The Brexit referendum of 2016 practically tore the UK apart. Where the 2012 Olympic Games had projected an image of confidence and inclusivity, Brexit suggested a nation in the grip of a collective nervous breakdown. The gloomiest predictions suggested that Britain was entering a new era of intolerance and nativist bigotry.

Marks BarfieldÔÇÖs Cambridge Central Mosque presents a difference picture, of a country that continues to deal with significant challenges around race and diversity, but which is hopefully not destined to sink into mutual recrimination and hatred.

No comments yet