Diversity and inclusion is the subject of our latest industry survey, conducted by Hays. Debika Ray looks at what the results say about the industry, and finds out what employers can do to improve the situation

║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs first survey of perceptions about diversity and inclusion across the industry has shown mixed results, with substantial minorities responding with positive views about the state of the sector, but equally large numbers saying the opposite ŌĆō that construction has a long way to go before it becomes reflective of wider society and makes everyone feel welcome.

ŌĆ£When looking at some of the results [ŌĆ”] it makes you think, ŌĆśwow, itŌĆÖs shocking that weŌĆÖre still at that pointŌĆÖ,ŌĆØ observes Amanda Clack, head of strategic advisory at property firm CBRE, who launched a book at Mipim last month called Managing Diversity and Inclusion in the Real Estate Sector.

This is ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs first general diversity survey (conducted by recruitment firm Hays) ŌĆō broadening out from previous years in which surveys focused on the different experiences of men and women ŌĆō so we donŌĆÖt have a full set of comparable data. However, the number of respondents ŌĆō at more than 1,000 ŌĆō is significant and the proportion of those that identify as having ŌĆ£protected characteristicsŌĆØ (see below) is broadly similar to industry averages.

ŌĆ£It is telling that so few people believe that diversity is a priority for their organisation ŌĆō clearly there is a lot of work still to be doneŌĆØ

Carol Hosey, Mace

This survey delved into peopleŌĆÖs perceptions of discrimination rather than any provable facts. However, as Theresa Mohammed, partner in legal firm Trowers & Hamlins, says, perceptions are important: ŌĆ£What this survey is showing is that, rightly or wrongly, people believe there are still widespread discriminatory views [in the industry], and that negatively impacts your workforce.ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs also important to note that the nature of this survey ŌĆō dealing as it does with an issue that affects groups under-represented within this relatively non-diverse industry ŌĆō means the balance of views will lean towards the opinions of those who have not experienced discrimination. The respondents were, after all, 72% male, 82% white and 92% able-bodied.

However, when the data is segmented by age, sex, race and disability, respondents from minority groups report far higher instances of discrimination than the general sample and are far less convinced of construction companiesŌĆÖ willingness or ability to tackle it effectively. So, what do the results tell us about perceptions of discrimination in construction and what should industry leaders be doing about it?

Protected characteristics

Under the Equality Act 2010, it is illegal to discriminate against someone because of what are called ŌĆ£protected characteristicsŌĆØ. These characteristics are:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion or belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

The 2010 Equality Act places responsibility and obligations on employers for direct or indirect discrimination against staff, job applicants and other parties by its employees, managers or agents.

For detailed guidance, visit

Delving deeper

When analysing the data, the varying experience of different groups becomes clear: while 82% of all respondents said they were never discouraged from entering the industry, this falls to 77% for women, 69% for black respondents, and 66% for people with a disability. In other words, more than one-third of respondents with a disability and just under one-third of black people were discouraged from entering the industry at all.

Most respondents (61%) said they felt all genders had equal opportunities for career progression, but a substantial minority ŌĆō 39% ŌĆō said they didnŌĆÖt. Again, this shifts when you look at women and men separately: only 46% of females said they believed there were equal opportunities for the genders, compared with 67% of males.

There was a similar trend when it came to pay, but with more dispiriting numbers: only 34% of respondents believed pay to be equal between the genders, compared with 26% who did not. When only female respondents were asked, the former number dropped to 27% and the latter rose to 38%. For men the opposite happened: 35% said pay was equal, while 22% said it was not.

ŌĆ£Line managers have attended training on diversity and inclusion because it was mandatory but that has not been enough to change their stereotypical viewsŌĆØ

Mary Pierre-Harvey, Oxford Brookes University

Chloe McCulloch: ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs diversity survey ŌĆō take a look around you

Richard Threlfall: Construction must admit it has a problem with diversity

Paul Grover: Being neurodivergent can help your career ŌĆō and your company

Experience of discrimination

Across all respondents, 39% said there had been an occasion when they personally had felt their chance of being accepted for a job were lowered because they possessed a protected characteristic, with 46% saying they felt their career progress afterwards had been impeded for that reason. And this is clearly a current issue: of these respondents who reported having personally experienced such discrimination, 59% (for recruitment) and 55% (for progression) said it had happened within the past 12 months.

Of those who said they had experienced barriers to recruitment, 46% perceived age to be the greatest obstacle, followed by ethnicity (37%), gender (34%), sexual orientation (10%), religion (8%), disability (6%) and mental health (4%).

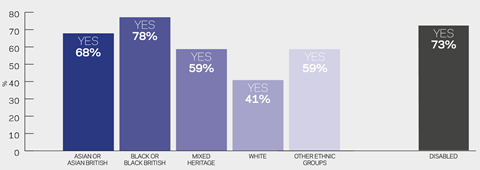

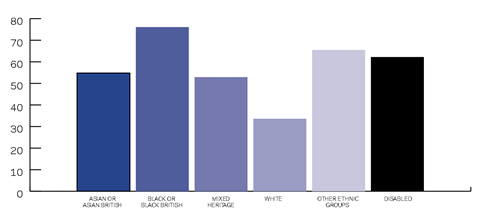

This finding of perceived discrimination against minority ethnic groups in the UK should be seen in the context that they are under-represented in the industry. The CITBŌĆÖs 2015 report on UK mobility found that ŌĆ£4% of the workforce is of BME ethnic origin, compared with a higher incidence of 10% in the UK population as a wholeŌĆØ. ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs survey found that 31% of black or black British respondents said they had been discouraged from entering the industry (compared with 16% of white), and a staggering 76% saying they felt they had been discriminated against when applying for a job ŌĆō well over twice the proportion of white respondents. Respondents of Asian background did not report higher than average discouragement from entering the industry, but over half said they experienced discrimination when applying for a job.

ŌĆ£At a time of transformation in our industry, we need to focus on creativity and empathy. Without these, our profession will struggle to thrive. Both are reliant on diversityŌĆØ

Katrina Kostic Samen, British Council for Offices

And once in the industry, discrimination is identified by many as a barrier to progressing to more senior roles. For career progression, age (40%) again came top, but this time matched by gender (40%), which came above ethnicity (32%) ŌĆō possibly reflecting the problems many women face as they reach towards higher roles while taking on disproportionate responsibilities in their personal lives.

When male and female respondents were split, women said gender was the top area in which their organisation could stand to be more diverse, while men selected age ŌĆō the high number of male respondents in the survey is one reason age ended up being selected as the biggest barrier overall.

While a consistent proportion of respondents felt their disability was a barrier to recruitment and progression, mental health was found to be a bigger obstacle in progression (7% of those who perceived an obstacle said they felt it was due to their mental health) than in recruitment (4%), perhaps because it can often be invisible in the recruitment process.

ItŌĆÖs not all about gender

Overall, these numbers reveal that employees are concerned about discrimination across the board and suggests companies should be too. However, even those firms that are striving to do better tend to have a narrow focus for their efforts.

ŌĆ£The focus continues to largely remain on gender, with LGBT+ inclusion, BAME and disability playing second fiddle,ŌĆØ says Jo Hennessey, global property and buildings chartered marketer at WSP and national chair of ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Equality, which works to improve LGBT+ inclusion in the sector. ŌĆ£[WeŌĆÖve found] over half of LGBT+ people still say they donŌĆÖt feel comfortable being open about their sexual orientation or gender identity on site.ŌĆØ

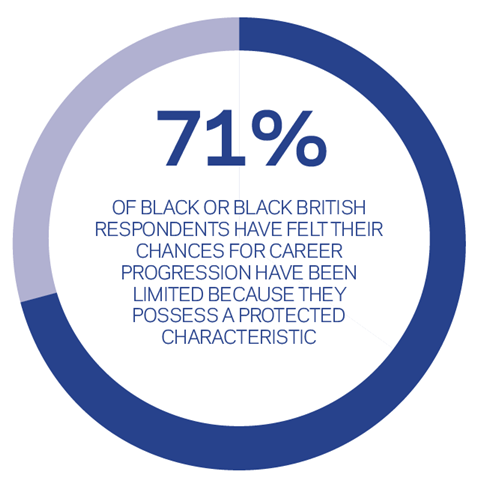

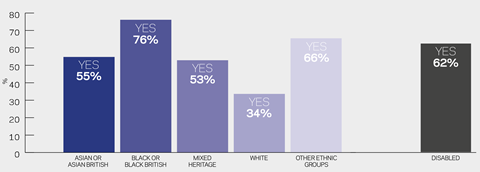

║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs survey results also indicate significant problems around how employees feel ŌĆō or are made to feel ŌĆō once in a role. It found, for example, that just 42% of black respondents said they felt secure in their job, while 60% of white respondents did; and 78% felt their chances for career progression were limited because of discrimination (compared with 41% of white people). In addition, some 20% of black respondents and 23% of respondents with an Asian background strongly disagree that their voice is ŌĆ£heard and respectedŌĆØ ŌĆō compared with 10% of white respondents.

Mary Pierre-Harvey, who has just been appointed as the first black female estates director in the UK, at Oxford Brookes University, agrees that the pay gap issue extends beyond gender: ŌĆ£I know there have been instances in my career where I was not paid in an equal manner to my white male colleagues.ŌĆØ

Mace is seeking to address this issue by reporting its ethnicity pay gap at the same time as its gender pay gap this year. ŌĆ£Until diversity is recognised as a priority across the whole industry, it will continue to limit our ability to attract the diverse talent we need for the future,ŌĆØ says Carol Hosey, its group HR director.

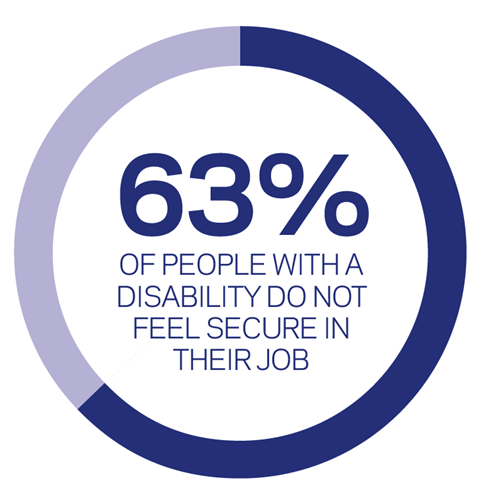

However, even reporting on gender and ethnicity may not paint the whole picture. The perception of discrimination against people with a disability is similarly striking. Just 37% of people with a disability said they felt secure in their jobs (compared with 60% of able-bodied people) ŌĆō and nearly twice the proportion (20%) as able-bodied (11%) strongly disagreed that their voice is heard and respected.

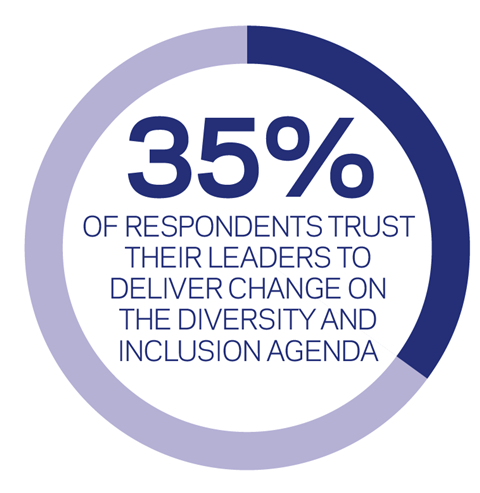

When it came to the respondentsŌĆÖ views on their management, less than half said the leaders in their organisations fully understood the impact of having a more diverse and inclusive company on talent attraction, creativity, innovation, employee engagement, customer insight and profitability. While 42% said diversity and inclusion was a stated priority for their organisation, just 22% said their leaders had specific goals to make it happen, while 35% said they trusted their leaders to deliver change and 34% said their leaders tended to challenge traditional viewpoints and ways of working.

Developing talent

Again, perception varied largely depending on whether respondents were part of a minority group that such initiatives may target. While 11% of white respondents strongly disagreed that their organisation works actively to develop under-represented groups ŌĆō specifically into leadership roles ŌĆō that figure rose to 20% each of black or black British, and Asian or Asian British respondents. ŌĆ£It is telling that so few people believe that diversity is a priority for their organisation ŌĆō clearly there is a lot of work still to be done,ŌĆØ Hosey says.

A decent proportion ŌĆō 40% ŌĆō said their organisation gave them access to mentors, and the same percentage said career development conversations with their line manager were open and transparent, but this contrasted with 29% who disagreed on the latter. More worryingly, 38% of respondents believed challenging cultural norms would be likely to damage their career opportunities and 34% said they did not work in a culture that encouraged debate and diversity of thought (compared with 38% that did).

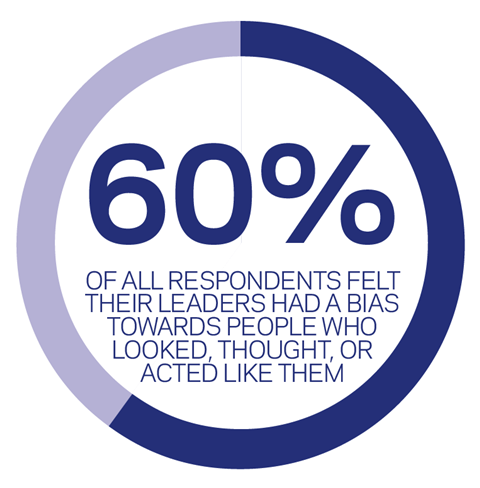

Only 37% said their managers were given training on diversity and inclusion, compared with 30% who said they were not. Strikingly, 60% felt their leaders had a bias towards people who looked, thought, or acted like them and 41% felt they were more likely to be promoted if they had a similar socio-economic background to the management. When asked for possible solutions, one respondent said: ŌĆ£I would like to see compulsory diversity and inclusion training and awareness programmes for all employees. I have seen these initiatives produce positive results and discussions in other companies and would be keen to see it implemented in mine.ŌĆØ

Hennessy believes greater endorsement of these values from the top of organisations is essential: ŌĆ£While weŌĆÖve seen some great examples in the last 18 months of CEOs speaking up on LGBT+ inclusion, the majority have remained silent and we need more of them to speak up. Creating diverse and inclusive workplaces needs leaders to step up, be role models, and to use their words to change hearts and minds. Line managers need the support for and to be accountable for creating inclusive teams.ŌĆØ

How to diversify your workforce

Some practical advice from Yvonne Smyth, group head of diversity and inclusion at recruiter Hays:

Start off by being self-aware: Leaders and managers must lead from the front when it comes to improving diversity and inclusion in their own teams and organisation. The survey results clearly demonstrate there is vast improvement needed in this area, as only 35% of respondents trust their leaders to deliver change on the diversity and inclusion agenda. Leaders should learn to recognise their own unconscious biases and implement regular training for managers in order to lessen the impact of these unconscious biases when it comes to hiring for their teams.

Review your recruitment materials: A job description and person specification are often the first interaction a candidate will have with your organisation, and these alone can offer important insight into your workplace culture. However, the words and phrases used can have a significant impact on whether or not a professional applies for a role. Review your recruitment materials for any biased language and ensure a wide range of social groups are depicted in any graphics, images and videos used for recruitment. Also include statements about your organisationŌĆÖs commitment to diversity and inclusion ŌĆō and donŌĆÖt forget to add a line that encourages applicants from all backgrounds to apply.

Maintain diversity throughout the selection process: Diversity shouldnŌĆÖt end after the initial application stage but must be sustained through the recruitment process. A heightened awareness of the potential impact of bias can be achieved by including diverse stakeholders when reviewing and selecting CVs or application forms as well as when interviewing. You could also consider undertaking blind decision-making ŌĆō removing from CVs all features that identify the candidate ŌĆō during the shortlisting process so that choices are based solely on the required skills and competencies.

Are leaders lacking?

Oxford Brookes UniversityŌĆÖs Pierre-Harvey points out that, beyond supporting diversity, the leadership itself needs to be diverse: ŌĆ£I have not seen evidence of employers actively working to develop under-represented groups, specifically into leadership roles. My experience is that line managers have attended training on diversity and inclusion because it was mandatory but that has not been enough to change their stereotypical views and less favourable treatment of black staff.ŌĆØ This was echoed in the words of one respondent, who said: ŌĆ£Our leaders need to be open-minded about what a leader looks like and how they behave.ŌĆØ

Katrina Kostic Samen, president of the British Council for Offices and founder of design studio KKS, says: ŌĆ£At a time of transformation in our industry, we need to focus on creativity and empathy. Without these two qualities, our profession will struggle to thrive. Both are reliant on diversity, an area where more must be done. We are, after all, building communities for occupiers.ŌĆØ

Yvonne Smyth, group head of diversity and inclusion at recruiter Hays, which conducted the survey, says: ŌĆ£Most organisations would be quick to refute any suggestion that their employeesŌĆÖ progression is limited due to gender, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, disability or socio-economic background. However, employers need to be aware that these perceptions do exist. Employees should indeed feel confident to express this sentiment, and there should be a process in place for any feedback to be responded to and acted upon where appropriate.ŌĆØ

Trowers & HamlinsŌĆÖ Mohammed points to the wider implications if these findings are ignored: ŌĆ£If what weŌĆÖre concerned about as a sector is retention of talent and addressing any skills gap, it is worrying that people feel their protected characteristics are blockers to career progression. There must be a reason for people to say that, which is going to do nothing for their motivation.ŌĆØ

She believes that, in order to make progress, the business case for diversity and inclusion ŌĆō rather than just the moral argument ŌĆō needs to be made, but points out that concrete numbers and analysis remain difficult to find: ŌĆ£I think we do need to prove what you get from having a diverse workforce, because that is what is going to ultimately tip the balance.ŌĆØ

It is hoped studies like this can contribute to providing those concrete numbers and a picture of industryŌĆÖs progress over time. As CBREŌĆÖs Clack says of our survey: ŌĆ£It will be fascinating to see what happens over a series of years.ŌĆØ

1 Readers' comment