Improved security and oil-funded mega projects make Iraq a land of rising opportunity for British companies starved of contracts at home. ThatŌĆÖs not to say working there is a picnic ŌĆ”

║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° reports from the countryŌĆÖs biggest construction site

The road from Kuwait City to Basra is known as the Highway of Death. It earned the name after American bombs turned a retreating column of Iraqi armour into a scene of smouldering carnage to end the first Gulf War. Nineteen years on, the road still bears the scars - shelled barns and splintered pylons - but is flanked by dozens of gas flares, slowly leeching dirty streaks of grey into the sky. It is this oil that is beginning to fuel reconstruction after decades of war and neglect: at the end of the Highway of Death, a vast stadium is rising out of the dust.

Basra Sports City is a $500m (┬Ż321m) project that will host the eight-team 2013 Gulf Cup football tournament. It is funded by a government finally tapping into the fourth largest ocean of oil in the world. IraqŌĆÖs burgeoning population - almost 40% of which is under 14 - needs infrastructure, and a $70bn (┬Ż45bn) investment package that includes 24 power stations and 3.5m houses was announced at the beginning of 2009. And Iraqi contractors are desperate for British expertise just as work in the public sector here all but disappears. Any day now, your boss might tap you on the shoulder and say: ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs this great project going in the Middle East. ItŌĆÖs in a country thatŌĆÖs had, er, a lot of bad press, but ŌĆ”ŌĆØ

When ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° visited Basra in 2004 with the British Army, the sectarian violence that later engulfed the country was on the rise. Six years on, ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° has returned to visit Basra Sports City, the biggest construction project in the country, and found that although rebuilding the country is no longer like working in a war zone, the threat of kidnap remains. There are more prosaic problems too: the difficulties of getting good materials; tedious bureaucracy; shoddy labour and the grim captivity of expat life. Yet the government, for all its political paralysis, is committed to a series of mega-projects that are luring British companies to a country of decreasing risk and rising opportunity.

The project

As we approach from the Kuwait border in an armed police convoy, the main 65,000-seater stadium at Basra Sports City, where work began in July 2009, dominates the landscape for miles around. Foundations for a secondary 10,000-seater stadium and the playersŌĆÖ accommodation have also been piled. Designed by US practice 360 Architects, the scheme is being built by Iraqi contractor Jiburi, while the British interest comes from intrepid QS and project management firm Baker Wilkins & Smith (BWS), which works as clientŌĆÖs representative for the Iraqi Ministry of Youth and Sport in a joint venture with architecture practice AMBS.

The main stadium is buzzing with around 2,000 workers. It has sucked in machinery from across the world: the contractor has bought eight Chinese tower cranes and a $4m, 1,200 tonne German crawler crane.

Security situation

Frank (we are unable to print full names for security reasons) is BWSŌĆÖ project lead. He could, if he were not a modest character, claim to be a veteran war zone builder, although he makes it clear he is not out here chasing the danger. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve got grandchildren,ŌĆØ he says, and insists that his family is perfectly calm about his regular excursions into war zones. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm not a hero. As soon as I need to wear body armour, IŌĆÖm out of here.ŌĆØ

A former RAF mechanic, after the invasion he worked in Iraq for three years for Kellogg Brown and Root, supporting the British military. He was then called in to complete a stalled hospital for the British Army in Camp Bastion, Afghanistan. He is utterly focused, controlled and pragmatic: ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm the guy who, if the client doesnŌĆÖt know the answers, knows where to get the answers. As clientŌĆÖs rep we can call on companies to check architecture, structure and functionality.ŌĆØ

As he weaves through the site past piling rigs and heaps of scaffolding, greeting the Iraqi engineers with bonhomie, Frank describes how he saw the security situation disintegrate after he began working in Iraq in 2003. ŌĆ£First you could drive around on your own. Then you needed a guard. Then you needed a two-car convoy. Then we needed to be choppered.ŌĆØ

But the bloody days of the full insurgency are now over, and helicopters are no longer needed, at least in Basra province - although Foreign Office advice is still against all travel to the country, except Kurdistan in the north.

A police convoy shuttles BWS staff from the border with Kuwait to a walled compound beside the site, guarded by a dedicated military police unit. ŌĆ£We could be kidnapped,ŌĆØ he explains. ŌĆ£Westerners are worth a lot of money.ŌĆØ Guards escort the British engineers on site too, because, as Frank puts it, ŌĆ£you donŌĆÖt know who might have a grudge against youŌĆØ.

An Iraqi supplier was killed in a car bomb attack on a market in Basra in July, but Frank is keen to put the risks into perspective. ŌĆ£Some parts of London or Manchester are more dangerous than the site I work on,ŌĆØ he says, and while black humour abounds among the expats, there is certainly no atmosphere of fear.

Materials and labour problems

A constant flow of rickety trucks that throw up a haze of dust keep the site stocked. But supply is an organisational and bureaucratic nightmare. ŌĆ£Materials mainly come from Turkey or Kuwait. You canŌĆÖt bring in caustic soda because it can be turned into explosives,ŌĆØ says Tony, senior project manager. ŌĆ£The common stuff sold in Basra is Chinese, which is shit.ŌĆØ He says the burden of importation and bureaucracy adds 50-100% in materials costs compared with a stadium project in the UK. The yellow tower cranes on site languished in Kuwait for months before they were allowed into Iraq. ŌĆ£This is a country of Sir Humphries - it is easier to not do it than do it,ŌĆØ Frank says. UK Trade & Investment warns of ŌĆ£wide spread corruptionŌĆØ throughout the country.

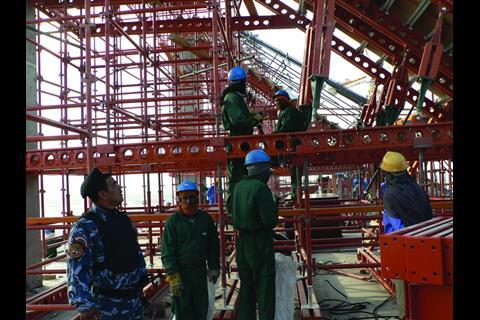

ŌĆ£The biggest problem this project has is the lack of quality labour - in quality building, and in health and safety,ŌĆØ adds Tony. About 70% of the workers are Iraqi. But a shortage of skilled labour means that Bangladeshis, Indians and Syrians - who operate the tower cranes - are flown in. Chinese workers may be needed when it is time to hoist on the roof. Lax building standards that create only cosmetic problems on a single-storey house could be disastrous on a much larger stadium. ŌĆ£The Iraqis have to learn not to get out by 10-15mm each time,ŌĆØ Frank says.

Most workers are sporting helmets - a huge improvement since the beginning of the project, Frank says - but some balance precariously on scaffolding without harnesses. Frank says that while there have not been any deaths on site, one worker was recently seriously injured in a 6m fall after he rejected a harness as an inconvenience. ŌĆ£HeŌĆÖll be crippled at best,ŌĆØ says Frank. Deafening grinders whir everywhere, but there are few ear defenders to be seen.

Many workers have scarves wrapped around their mouths to mask the awful mixture of smells: a petrochemical stench from the gas flares across the horizon, dust constantly kicked up by the trundling supply lorries, and sewage spilling out from Basra into the Shatt-Al-Arab waterway.

The heat of the summer, which can reach 50┬║C, means concrete pouring in the warmest months has to be done between 4pm and 7am, with ice in the water. The ground is far from ideal for piling anyway, the loose clay demanding 24m piles to secure a decent grip.

New arrivals to the site are told to ŌĆ£assume machinery is in poor conditionŌĆØ, which means no brakes, among other things. One crane has to be moved around using picks and shovels because its chassis engine doesnŌĆÖt work. But the site hums with constant activity, not chaos or apathy. You have to keep reminding yourself which country you are actually in.

Over budget and a bit late

The consensus is that the first phase of the project will be ready in time for the 2013 Gulf Cup, and new swimming pools and indoor arenas will follow after that. But it will probably come in over budget and slightly, although not fatally, late. The official cost of the first phase, which includes the main stadium, is $500m (┬Ż321m), but several in BWS think the final cost will be more like $1bn. Bureaucracy has inevitably shifted the $500m estimate, only ever a ŌĆ£politicalŌĆØ figure, steadily upwards. The original completion date of April 2012 has now slipped to ŌĆ£mid-2012ŌĆØ, according to Abdullah Al Jiburi, head of main contractor Jiburi.

Basra Sports City is JiburiŌĆÖs first stadium, but unlikely to be the last. It has 3,000 staff, a turnover of more than $500m (which it aims to double next year), and is bidding for a 100,000-seat stadium near Baghdad with Populous, and a 10,000-seater near Najaf. ŌĆ£We are ready to bid if we have a chance on the stadiums in Qatar [for the 2022 World Cup] ŌĆ” so we need consultants,ŌĆØ Jiburi says.

Jiburi insists his firm needs British consultants. ŌĆ£We need the right people; the British and American companies in the last five years were not up to scratch,ŌĆØ he complains. ŌĆ£There are not enough British in Basra. I would encourage them to get in contact with us.ŌĆØ He would like to see a kind of British-Iraqi chamber of commerce to help UK companies work in Iraq.

Expat life

It is a short, suspension-wrecking drive to the BWS compound, home to half a dozen Brits because a Basra hotel would pose too much of a kidnapping risk. Accommodation is a set of rather soulless, but perfectly functional Portacabins. Social trips into Basra are not possible for security reasons, leading locals to affectionately nickname the compound ŌĆ£the Basra GuantanamoŌĆØ.

ItŌĆÖs fair to say that working in Iraq was not the first choice of many of the British BWS employees, several of whom moved out after redundancy in the UK. For others, itŌĆÖs simply the toughest gig yet in a career in the Middle East. Wages for all Western expats in the country have fallen dramatically over the past two years as the security situation has improved. One BWS employee earns ┬Ż60,000 a year, ŌĆ£which is not much for a tough lifeŌĆØ, and Frank, while coy about his exact wage, reveals that he is far from being on triple figures. However, there are no taxes and almost no outgoings, so they get to keep close to 100% of their salary.

As proof of being able to operate under the very toughest conditions, experience in Iraq is second to none. But Tony warns that companies may be reluctant to employ you on your return.ŌĆØOnce an expat, always an expat. Companies are nervous of expats returning. They think youŌĆÖre going to be like Andy McNab,ŌĆØ he says.

Neglected city

The gleaming promise of the Sports City, which will cost between 1-2% of the governmentŌĆÖs entire income for 2009, is that it will help change the image of Iraq across the globe. But it is in brutal contrast to Basra itself, which can be seen sprawling from the top of the stadium. When ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° visited in 2004, the city was getting $2.9bn (┬Ż1.9bn) of American money to rebuild utilities. Iraqi engineers who live in the city say that this is happening, but seven and a half years after the invasion, basic utilities are still lacking.

Ali Mousawi, the JV lead for AMBS and go-to man for the ministry, says: ŌĆ£Everything is needed in Basra. We get four to five hours of electricity, and then it goes off for two hours.ŌĆØ He says all the hospitals need refurbishing. In the oppressive heat of the summer, home air-conditioners fail and have to be run off private generators, eating up 10-20% of an Iraqi engineerŌĆÖs wage. One, Wasim, says: ŌĆ£You work all day, and go back exhausted but then thereŌĆÖs no electricity. The generators are consuming our income. You have to pay for everything.ŌĆØ

Bridges to ease congestion are being erected, and roads repaired, although after a year they are said to be degrading. A childrenŌĆÖs cancer hospital has just been finished, as has a jail and offices for the Iraqi army. But another BWS Iraqi engineer, Nadal, is exasperated by the delay. ŌĆ£Eight years without electricity and water: we have the oil but we donŌĆÖt have the water. ItŌĆÖs continuous suffering,ŌĆØ she says, and, just on cue, the electricity cuts out in the compound. But no one I speak to says they would rather be living under Saddam.

Nonetheless, the Sports City is a project that employs roughly 1,500 people from a city with an unemployment rate thought to be around 40%. For director-general Kamil Brahi, from the ministry of youth and sport, it is as much about making Basra attractive to Western companies - who crucially can help get oil out of the ground - as it is about sport. ŌĆ£Basra Sports City will have electricity, water, sewerage, communications, internet and television which will not suffer from the problems in Basra,ŌĆØ says Brahi when asked about the infrastructure problems in the city, which has a population of about 3 million. It is also about signalling to the world that Iraq is safe and organised. ŌĆ£In the past the Iraq football team was playing outside of Iraq.

But now Iraq will be playing inside Iraq, which will bring business,ŌĆØ Brahi says.

Potential for UK companies

Be under no illusions about IraqŌĆÖs infrastructure, warns Frank. ŌĆ£Iraq at present is a third world country. But the Iraqi people and oil have huge potential. It is not Abu Dhabi or Dubai, but it could be.ŌĆØ Be prepared for the bureaucracy to squeeze margins, and for endless frustrations. ŌĆ£At present the job is not seriously profitable,ŌĆØ he says. He estimates 20% of his time is spent chasing up things he would never have to deal with in the UK, such as repair of a toilet that had been inspected twice before it broke on first use. ŌĆ£I have been known to let rip at people. But my best stress relief? Rock and roll.ŌĆØ With this, Frank blasts out Badlands by Bruce Springsteen from his hefty office speakers.

For all the rides through kidnap country, bureaucratic frustrations, logistical problems and lack of booze, Frank and BWS are set on staying. ŌĆ£A year ago this was rather a toe in the water job,ŌĆØ he says. ŌĆ£But we will be looking for more work. We could be in Iraq for some while.ŌĆØ You might even want to follow them.

For more from ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° in Iraq, you can tour the country using an interactive map, read David MatthewsŌĆÖ blog and take a look around the site by video at

Could you live in Iraq?

Travel and shifts: BWS employees work for eight weeks in Iraq, and then get two off to recoup in the UK. For now they reach the site via an uncomfortable overnight flight to Kuwait City, but Emirates is starting direct flights to Basra airport in February.

Creatures: Camel spiders, while not the novocaine-injecting, 40kmph face-attacking arachnid horrors of internet legend, can still be a nuisance with a powerful bite. Rabies in dogs and cats is common, and packs of wild dogs sometimes prowl the site.

Exercise: A gym room has recently been installed in the BWS compound, but the security situation makes more outdoor exercise rather more difficult. If you do go jogging outside, a guard will have to come huffing and puffing in tow. BWS did just manage to get a Wii Fit through the Iraqi border on their last visit, however, as an early Christmas present.

Down time: The site is almost completely dry, with one or two cans of beer after dinner in front of Sky Sports an occasional treat. ŌĆ£Not all expats can handle this job,ŌĆØ Frank says. ŌĆ£Most expats like drink, smoke and talking about what theyŌĆÖve been doing with other expats. If you had an excess of testosterone, with no women here, you would go up the walls.ŌĆØ

WhoŌĆÖs operating in Iraq?

Parsons Brinckerhoff Working on the 10 year development of electricity supplies in Kurdistan

Cyril Sweett Providing services for 10 - 15 projects across the country including water treatment, sewage, roads, power plants and desalination plants.

Mott MacDonald Engineering and procurement services to develop gas fields

Pell Frischmann Consultants with projects in Kirkuk and Baghdad

URS Scott Wilson Designed new airport at Erbil, Kurdistan

Costain Involved in construction of Erbil airport

Halcrow Working on dam projects in Kurdistan; looking at marine work in southern Iraq

No comments yet