The government’s new PPP, Project Phoenix, was hailed as the NHS’ big hope, bringing much-needed cash to the ailing healthcare estate. Nearly a year on, have any hospitals been fixed up yet? And what are the other prospects for desperately needed additional funding?

Boris Johnson’s call at a cabinet meeting last month for an extra £100m a week for the health service was viewed by many as a cynical, attention-grabbing stunt. However, the NHS’ crumbling estate could certainly do with a share of that cash. Amid the dire headlines about hospital patients stuck on trolleys due to lack of beds, lack of maintenance might seem a humdrum issue. But the extent of disrepair across the NHS is accelerating, according to figures recently published by NHS Digital.

The total cost of eradicating the maintenance backlog rose by 11.5% from £4.97bn in 2015/16 to a record figure of £5.54bn last year, an increase of more than 40% since the mid-2000s. This latest figure was double the Department of Health and Social Care’s (DHSC) £2.7bn limit on NHS providers’ capital expenditure.

And the problem has escalated over the past two years, most rapidly in the so-called ‚Äúhigh-risk‚ÄĚ backlog, which doubled from ¬£458m in 2014/15 to ¬£947.1m last year. The NHS judges ‚Äúhigh-risk‚ÄĚ as where repairs or replacement must be given urgent priority in order to prevent ‚Äúcatastrophic‚ÄĚ failure and ‚Äúmajor disruptions‚ÄĚ to clinical services, which could result in serious injury and prosecutions.

‚ÄúNot only are new projects not happening, investment in [‚Ķ] maintenance is falling [‚Ķ] as money is diverted to frontline and more critical services‚ÄĚ

Jonathan Puddle, Aecom

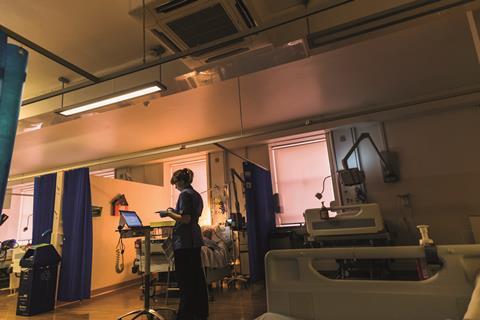

The NHS regulator has raised concerns that the existing level of capital expenditure is inadequate. The extent of disrepair varies dramatically across the NHS, says Jonathan Puddle, head of healthcare at Aecom for UK and Ireland: ‚ÄúCertain trusts are still delivering services in Victorian wards that are not fit for purpose. They desperately need additional funding in order to get out of those conditions to a place where they are delivering 21st-century healthcare.‚ÄĚ

The problem is most graphically illustrated by the Imperial College Hospital Trust, which has five hospitals across north-west London. It accounts for around one-third of the NHS’ total high-risk maintenance backlog. The 147-year-old Cambridge wing of St Mary’s hospital, in Paddington, which is where the BBC’s Hospital fly-on-the-wall documentary was filmed in 2016 and 2017, suffered ceiling and floor collapses last summer. A whole ward had to be closed for the rest of the year, resulting in the loss of 30 beds, while repair work was carried out.

Imperial is in the process of redeveloping St Mary‚Äôs. The first phase ‚Äď an eight-storey outpatients building ‚Äď was granted outline planning permission in September.

Naylor review

But what of the wider NHS estate? The government-backed Naylor review in March last year set out the scale of the challenge. In that report, Sir Robert Naylor, former chief executive of University College London hospital, made clear that only a massive injection of cash into the system would restore it to good health. Soon afterwards, in the pages of ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, we looked at a new and little-publicised public-private partnership that was being developed with this very aim in mind, called Project Phoenix. So, almost a year later how much, if any, extra money has been ring-fenced for healthcare buildings, and have the attempts of the NHS to harness private finance actually resulted in any projects coming to market under the new PPP model?

One of the chief factors fuelling the increase in backlog maintenance is the siphoning of money from NHS capital budgets to prop up frontline delivery over recent years. Aecom‚Äôs Puddle says: ‚ÄúNot only are new projects not happening, investment in programmes like planned preventative maintenance is falling backwards, and continues to fall backwards as money is diverted to frontline and more critical services.‚ÄĚ

The choice between paying nurses and carrying out maintenance may look like a no-brainer to a cash-strapped hospital manager. But it‚Äôs a false economy, warns Sally Gainsbury, senior policy analyst at the Nuffield Trust, a health policy charity. Old facilities are more expensive to operate and potentially less safe clinical environments, she points out: ‚ÄúWhen you have an old and dilapidated building, it‚Äôs harder to keep clean and infection-free, just like an old house.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúIt‚Äôs clear the public sector is going to be used to balance the economy [‚Ķ] The early indications are that capital funds are being made available‚ÄĚ

Roger Pulham, Gleeds

Project Phoenix

‚ÄúThere will be a lot riding on it,‚ÄĚ says Aecom‚Äôs Jonathan Puddle, referring to Project Phoenix, the NHS‚Äô much heralded but delayed public private partnership (PPP) vehicle.

The initiative was dreamt up to help deliver the estate revamp elements of the NHS’ five year plan, which started in 2015.

Under the blueprint for Project Phoenix, which is expected to be worth up to £5bn, England will be divided up into six regions.

Within each region, the biggest of which covers the whole of London and the South-east, a single consortium will be picked to deliver PPP projects for NHS trusts and clinical commissioning groups.

Each consortium will be made up of a mix of developer, funder and manager partners. Community Health Partnerships, which has been developing Project Phoenix for the health department, holds a 20% stake, according to a briefing to a King’s Fund conference last year by the agency’s commercial director Graham Spence. At least one consortium, the Nottingham-based One Health Partnership, has been set up to bid for potential Project Phoenix work.

Within each region, developers are expected to bring forward five to 10 projects, worth £5m-£50m apiece, including a mix of acute, primary and mental health schemes

It will offer NHS providers with an alternative, particularly for bigger projects, to the existing LIFT programme.

The CHP business plan for the current financial year stated that Project Phoenix will be ‚Äúready to go to market‚ÄĚ in 2017/18. However, the initiative is understood not to have yet received sign-off by ministers when ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý went to press.

Bed shortages

Meanwhile, the NHS’ built estate is bursting at the seams. Gainsbury recalls that in the mid-2000s, a bed occupancy rate of 85% was regarded as an acceptable benchmark. These days, by contrast, she says, many hospitals are operating at 98% rates, which allows very little time to clean beds between patients or any leeway in case a major accident happens.

Gainsbury says a study carried out in south-west London showed that the problem is not simply bed blocking by elderly patients who should be in nursing homes. ‚ÄúIt was found that [patients] can‚Äôt just be discharged because they still have quite intensive needs.‚ÄĚ

The solution is therefore not just better management of existing facilities. ‚ÄúMore beds full-stop would be a good start,‚ÄĚ adds Gainsbury. Some hospitals have been looking at converting wards into ‚Äústep-down‚ÄĚ nursing accommodation (for patients who no longer need acute care) in order to free up much needed acute beds, she says.

The existing P22 procurement framework, which has been up and running since late 2016, has so far generated 62 projects with an estimated total value of £1.7bn. The projects coming via P22 are generally worth £5m to £20m, although some can be as large as £100m.

Lewis Parker, healthcare director of Kier, says the company has so far been awarded work via P22 on 20 schemes worth about £400m in total.

And after years of cutbacks in capital spending, further relief is at hand. In November’s autumn Budget, chancellor of the exchequer Philip Hammond trumpeted an extra £10bn of investment in NHS buildings and equipment over the course of this parliament.

Of the £10bn headline figure, just under £4bn is new direct government funding. NHS providers will be expected to raise the balance from either private finance or asset sales. The government has said in its official response last month to the Naylor review that it aims to raise £3.3bn through the disposal of surplus land. It is also forming a national strategic estates planning service to assist with this land disposal and to prioritise local and national estate investment needs.

‚ÄúIf we could deliver solutions more quickly through a streamlined process, that would be more attractive and beneficial to the NHS‚ÄĚ

Jonathan Puddle, Aecom

After years of capital squeezes, any new funding is to be welcomed, particularly in light of the fact that it is more than the extra money awarded for frontline services in the Budget. ‚ÄúIt will go a long way to helping,‚ÄĚ says Parker, who was ‚Äúpleasantly surprised‚ÄĚ by the chancellor‚Äôs announcement.

‚ÄúThe government has recognised that money needs to be put into supporting the NHS on the front line. It was getting to a point where something had to be done ‚Äď eventually you have to start putting in some cash,‚ÄĚ he says.

Roger Pulham, a director at Gleeds, suggests the cash injection was also prompted by a desire to prop up the economy as the UK heads into Brexit-related uncertainty. ‚ÄúIt‚Äôs clear the public sector is going to be used to balance the economy, and health is always one of the big beneficiaries.‚ÄĚ

Work is already starting to trickle through as a result of November‚Äôs announcement, with the first tenders likely to start to surfacing from the middle of next month, he adds: ‚ÄúThe early indications are that capital funds are being made available.‚ÄĚ

The first organisations to procure are likely to be arm’s-length health bodies such as the NHS Blood and Transplant Agency, which is seeking a provider of project management services for £8m worth of a backlog maintenance programme. Such bodies are usually smaller organisations with flatter structures that can take decisions more swiftly. Consequently, says Pulham, they have fewer bureaucratic hurdles to negotiate than do NHS trusts.

The lion‚Äôs share ‚Äď some ¬£2.6bn ‚Äď of the new direct capital funding has been earmarked for projects developed by the sustainability and transformation partnerships (STP), which have been set up to rationalise services in local areas. The first 10% tranche of this funding has been allocated to 12 projects (see panel on previous page), where the STPs‚Äô plans are deemed to be most advanced.

Projects allocated funding through stps

- Barnsley Hospital Children’s Emergency Department and Assessment Unit scheme

- Doncaster Urgent and Emergency Care scheme

- Leeds Community Child and Adolescent Mental Health Inpatient Unit scheme

- Chesterfield Urgent Care scheme

- Russell’s Hall Hospital Dudley Urgent Care Centre scheme (Black Country)

- Birmingham Children’s Hospital Emergency Department scheme

- South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust Out of Hospital Care scheme

- Mid and South Essex Acute Hospitals reconfiguration scheme

- South West London and St George’s NHS Mental Health Trust Estates Modernisation scheme

- Frimley Out of Hospital Integrated Care Hubs scheme

- Bracknell Forest Heathlands scheme

- Chiltern and Aylesbury Vale Primary Care Hub scheme

Reliance on private finance

However, Conor Ellis, RLB head of healthcare, is worried about the extent of the Treasury’s reliance on private finance projects, which take longer to get off the ground than those directly bankrolled by the state.

Ellis points to the delayed introduction of the DHSC‚Äôs planned new public-private partnership (PPP) model for the NHS known as Project Phoenix, with an estimated value of ¬£5bn. ‚ÄúSchemes like Phoenix take a reasonable amount of time to come through the system,‚ÄĚ he says. Unlike PFI, where the private contractor wholly finances projects, the new initiative will see the public sector take a share of the risk.

Phoenix has taken a long time to take wing (see panel, right), however. The initiative was due to have been launched by October last year, according to those briefed by the DHSC. Then Community Health Partnerships, the agency that has been charged with developing Phoenix, said in its 2017/18 business plan that the new model would be ready to go to market by the end of the current financial year.

But the Treasury is still understood to be reviewing the latest version of the Phoenix business case, meaning sign-off is not expected until April, so it is now not set to hit the market until the summer. The Treasury has been contacted for comment.

RLB‚Äôs Ellis says the delay is frustrating. ‚ÄúThe whole industry wants capital and to be allowed to get on with it.‚ÄĚ

Puddle also says that he is frustrated about how long it has taken to deliver but believes the wait will be worth it if the model delivers the right solution. ‚ÄúMaking it easy and attractive for the private sector to invest in the healthcare sector is important. I would prefer to wait and have a solution that is more attractive to private investors rather than rush something that doesn‚Äôt get the right response from the market,‚ÄĚ he says.

This includes ensuring that the mechanism, supported by ‚Äúclear and robust‚ÄĚ documentation, isn‚Äôt open to legal challenge. Puddle says he doesn‚Äôt want to see a repeat of the disputes surrounding the SBS (Shared Business Services) consultants framework, which had to be cancelled after being challenged by Turner & Townsend in 2014.

‚ÄúIt [Phoenix] will be a heavily fought over and competitive tender because it‚Äôs only one winner per region, so particularly in the South-east there will be a lot riding on it. Considerable legal due diligence is required to ensure that everybody is treated equally and you don‚Äôt open yourself to being challenged at the end of the process and having to start all over again.‚ÄĚ

Streamlining needed

Most importantly, Puddle is keen to ensure the process is as ‚Äústreamlined‚ÄĚ as possible. At present all NHS projects have to go through three separate business case processes ‚Äď strategic outline case, outline business case and full business case. If a project is over ¬£50m in value, the process has to be approved by the clinical commissioning group, NHS Improvement, NHS England and the Department of Health ‚Äď and sometimes the Treasury as well. At each stage, all three business cases need to be approved. Consequently it can take anything from three months to a year to sign a deal.

‚ÄúIt definitely puts people off,‚ÄĚ says Puddle, pointing to the contrast with developers‚Äô greater appetite for getting involved in the higher education market. ‚ÄúWe don‚Äôt see that level of private investment in the healthcare market at the moment.

“You have to do all of that bidding at your own cost and own risk and then it takes a long time to get through the application process. Investing takes a lot of time and effort before you can see a return on investment.

‚ÄúIf we could deliver solutions more quickly through a streamlined process, that would be more attractive and beneficial to the NHS and would certainly be more attractive to those involved in delivering projects ‚Äď and would help them see that this is worth investing in.‚ÄĚ

Despite the backlash against private finance in the NHS, which has risen to a new pitch following the collapse of Carillion, Puddle argues that the health service will still require PPPs. ‚ÄúThe reality is that the government is not going to be able to afford the capital funding needed to get the NHS back onto a long-term financially sustainable place, so we need this vehicle.‚ÄĚ

The woes of the health service were underlined this week when it emerged that cancer and heart disease patients have had potentially life-saving operations delayed due to wider pressures on acute hospital beds. Private finance is not exactly flavour of the month, but they and many others may not care that much if creative solutions can deliver much needed improvements to the creaking NHS estate.

This week's poll: Is there still a place for private finance in the NHS?

‚ÄĒ ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý News (@ļŕ∂ī…Á«ÝNews)

No comments yet