TootingŌĆÖs Graveney School teaches architecture to its schoolchildren, invites architects to lecture, and counts architects among its alumni. So when it needed a new sixth form block on a tight budget, what would it come up with? Ike Ijeh takes a look. Photography by Kilian OŌĆÖSullivan

While the RIBAŌĆÖs recent changes to professional architectural tuition have garnered much publicity, there is virtually no debate about whether architecture should be taught in schools. Only a handful of schools in the UK offer architecture as an A-level course, and even fewer provide an opportunity for younger pupils to study the subject.

One of the few schools that does provide such an opportunity is Graveney School in Tooting, south London. Architecture is offered as part of the Year 9 curriculum and the school proudly talks of fostering a ŌĆ£culture of architectureŌĆØ that has led to its winning several Junior Open House competitions and providing workshops and presentations from high-profile industry figures and practices such as engineer Chris Wise and architect Make.

So naturally, when the prospect of building a new sixth form block for the school arose, it provided the perfect opportunity for the school to put its ideas into action. The finished result opened last month and has been designed by architect Urban Projects Bureau (UPB). And even more serendipitously, the UPB assistant architect assigned to the project was a former pupil of the school who had first been introduced to architecture by its pioneering course.

The new ┬Ż1.04m sixth form block is also interesting for several more conventional reasons. At a total construction cost of about ┬Ż1,275/m┬▓, the 800m┬▓ block is extremely competitively priced and had a budget comparable to projects built under the coalition governmentŌĆÖs flagship Priority Schools ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Programme (PSBP).

Moreover, it achieved this competiveness while still rejecting PSBPŌĆÖs default standardisation procurement route. Despite the price, it was still also able to maintain a robust design quality characterised by the use of specialised, high-performance materials such as cross-laminated timber (CLT) and a shimmering, translucent polycarbonate facade.

In with the new

Graveney School occupies an enviably picturesque, parkland campus just south of Tooting Common and can trace its origins back to the late 1660s. The school operates from an eclectic group of buildings clustered around Furzedown Hall, a fine grade II-listed Regency mansion that dates from 1796 and now accommodates the art, music and English departments.

Other buildings include more familiar red-brick Edwardian institutional buildings and a rather incongruous brutalist 1960s tower previously leased to the former Central St MartinŌĆÖs art college. The school is also a well-performing one ŌĆō it received an ŌĆ£outstandingŌĆØ Ofsted report in 2011 and became an academy shortly afterwards.

UPBŌĆÖs involvement with the school began when it was invited to compile a feasibility study on how a restricted access public road that cuts right through the school campus could be reconfigured for more recreational and educational purposes. At the same time the school was in the process of applying for a post-BSF (║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Schools for the Future) Academies Capital Maintenance Fund for a new sixth form block to the rear of the site.

The schoolŌĆÖs initial idea was to save money by purchasing a series of prefabricated single-storey container-like blocks and stacking them together to form the new sixth form accommodation. However, concerns about the quality and suitability of this approach grew and were brought sharply into focus by the poor condition of the recently completed technology block built using the same system.

To this day the building continues to exhibit a host of structural and cosmetic problems which did not bode well for any potential new building constructed using the same prefabricated system. Moreover, the site planned for the new sixth form block was right beside Furzedown Hall and there were serious heritage and conservation concerns about placing what would essentially have been an inelegant stack of prefabricated cabins right next to a listed building that was also the schoolŌĆÖs showpiece historic property.

It was at this point that the idea of using a different, more ambitious construction system was proposed. The technology block had cost ┬Ż1.6m and the school had earmarked a similar budget for the sixth form building. However, UPB was convinced that it could deliver a bigger and better building for less money. Now the building has been successfully completed, they are able to cite three principal reasons why this was the case.

The first reason was the early feasibility process, which involved a far greater degree of brief adaptation and early-stage consultant contribution (particularly from the quantity surveyor) than is often the case on comparable projects. UPB assistant architect assigned to the project and former Graveney pupil Joseph Zeal-Henry explains how this process worked.

ŌĆ£We were fortunate right from the start in already having built up a close relationship with the school during the road project, which proved to be hugely beneficial. The next big step was our being able to lead the process that helped conceive and develop the brief. This meant we were able to advise the client on a whole host of issues and considerations that helped them move on from their initial ŌĆśwe think we can only afford mobile site hutsŌĆÖ approach.

ŌĆ£And finally, a crucial element of this process was the early involvement of consultants such as the quantity surveyor and CLT manufacturers. This meant that every element of the design proposal could be thoroughly tested and measured with regard to cost, efficiency and practicability. This provided a huge degree of confidence and certainty right from the start of the project and whilst the design itself was still developing.ŌĆØ

Zeal-HenryŌĆÖs comments touch upon the second reason why the school was delivered on budget: the use of CLT. CLT is often considered an expensive structural solution but a clever aesthetic decision enabled the design team to recoup any additional capital cost the choice of CLT may have presented.

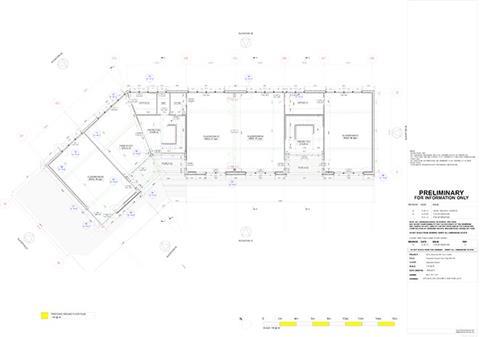

The sixth form block is a two-storey CLT frame building with a translucent, polycarbonate front facade. But the CLT is not only deployed as the buildingŌĆÖs structure, it is left exposed as the chief internal finish for walls and floors too. Therefore by using CLT as both structure and finish, the project was able to largely dispense with the entire budget initially allocated for internal finishes.

Aesthetically, the result is a building that subtly combines a natural feel with robustness and durability, the latter two characteristics being particularly welcome on a building that must withstand a barrage of teenage sixth-formers. The universal use of CLT not only presented cost savings but provided a speed of assembly that delivered programme and construction efficiencies also.

The principal facade construction typifies the technical coordination and efficiency of the timber structural solution. The double-skin facade is externally finished in a translucent layer of Rodeca polycarbonate sheeting which acts as a rainscreen and is fixed to the internal glulam timber frame. The glulam frame itself has sporadic openings to allow natural light to pass through the Rodeca during the day and for internal artificial light to enable the building exterior to glow at night.

The solid parts of the glulam facade frame are fitted with 50mm of rigid insulation wrapped in a breather membrane. The internal airtight envelope which this insulates is then composed of either CLT or polycarbonate panels whose location is determined by the window openings cut into the elevation. Where the Rodeca gives way to conventional glass windows, these are fixed within a powder-coated aluminium frame fixed back to the glulam structure with aluminium clips.

The third and final reason why the building was able to meet its demanding budget relates to circulation. Essentially it doesnŌĆÖt have any, as Zeal-Henry explains. ŌĆ£║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° corridors would have tipped the building over its budget so instead we have two entrance and staircase cores which each serve two upstairs classrooms and the downstairs classrooms can be reached by external doors placed on a recessed ground floor porch that runs the full length of the facade.ŌĆØ

Spatially, this novel approach works well. It encourages a stronger connection between inside and out, and creates a remarkably tight and efficient layout, which places even greater spatial and aesthetic emphasis on the twin stair cores than might otherwise have been the case.

Taken in themselves, the three cited reasons for the Graveney sixth form blockŌĆÖs efficient budget, feasibility, materials and circulation are hardly groundbreaking, but it is their clever deployment on a small but powerfully imaginative building that is significant.

Moreover, their utilisation on a school already so actively engaged with architecture carries real resonance. ŌĆ£EveryoneŌĆÖs an architectŌĆØ, explains school principal Graham Stapleton enthusiastically, ŌĆ£or at least everyoneŌĆÖs exposed to architecture. Design informs behaviour so itŌĆÖs natural that itŌĆÖs a subject that we as a school should be interested in.ŌĆØ

And Stapleton readily attributes the ŌĆ£tenacity, drive and beliefŌĆØ required to deliver the schoolŌĆÖs architecture programme to Graveney teacher and pioneering programme founder Neil Pinder. Pinder himself sees the new block as a culmination of his several years of work in raising the profile of architecture within the school and is pleased with the results.

ŌĆ£When I first had this idea of this shimmering pavilion it didnŌĆÖt seem possible but now itŌĆÖs a reality. Some of our students come from underprivileged backgrounds so itŌĆÖs important to use the block as a catalyst for creativity and prove to them that anything can be built around creativity and belief.ŌĆØ

Project Team

Client Graveney Trust

Architect Urban Projects Bureau

Main contractor Ashe Construction

Structural engineer Furness Partnership

M&E consultant Stuart McCurry & Partners

Quantity surveyor MorganCarr

No comments yet