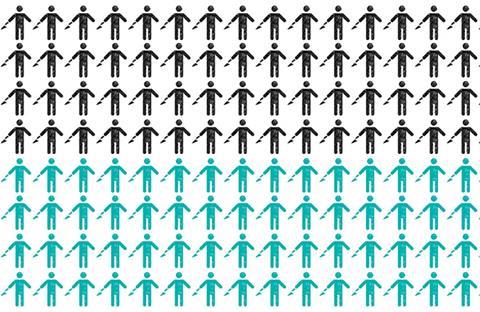

For construction to exploit the economic recovery, it will need about 30,000 new skilled workers each year - thatŌĆÖs about double the number of apprentices the industry is training up. David Blackman looks at the challenges that are fast stacking up

The past decade has seen a boom in apprenticeships. Back in the mid-noughties, the dream of most parents was to get their child onto a university course, almost irrespective of its quality. Reflecting the pro-higher education zeitgeist, 450,000 undergraduates enrolled on university courses in 2005/06, more than two-and-a-half times the 175,000 individuals who started an apprenticeship in the same period.

But fast-forward nearly 10 years and the humble apprenticeship is flavour of the month, with the Office for National Statistics estimating that 440,400 apprenticeships were started in 2013/14. But construction, one of the traditional apprenticeship mainstays, hasnŌĆÖt really joined the party. Recently published ONS figures show that just 9,306 construction apprenticeships were completed across England and Scotland last year - the lowest figure recorded in more than a decade.

On the eve of National Apprenticeship Week, ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° explores how the industryŌĆÖs reluctance to train construction workers continues to exacerbate the skills shortage. We reveal the conclusions of a study, soon to be published by the think tank Demos, on how construction remains a turn-off for many would-be apprentices. And we examine why many fear the governmentŌĆÖs plans to reform the apprenticeship system could make the situation worse.

The 9,306 construction apprenticeships completed last year, which represents a 4% drop on 2013ŌĆÖs already low figure of 9,688, continues a decline from a high point in 2009 when 16,947 apprentices finished their training.

The good news for the industry, though, is that the number of those starting construction apprenticeships has increased for the first time since the onset of the recession. The number of apprenticeship starts in 2014 was 18,493, 14.8% up from the previous yearŌĆÖs figures.

This positive news is reinforced by the Construction Industry Training BoardŌĆÖs latest Employer Attitudes Survey. Of the 1,500 construction employers surveyed, 26% reported that they had taken on apprentices in 2014, up from 20% in 2013 and the highest level since 2008.

Gillian Econopouly, CITB head of policy, says: ŌĆ£Businesses have better visibility on their order books and they are feeling a lot more comfortable about taking on apprentices.ŌĆØ

Staying power

But this yearŌĆÖs heartening level of starts is still below the 19,160 apprentices who began their training in the depths of the 2009 recession. In addition, many who start construction apprenticeships donŌĆÖt complete them. The ONS figures show that 17,630 construction apprenticeships were started in 2011, which means nearly half dropped out before 2014.

Econopouly says the drop-out rate can be accounted for by the fact that ŌĆ£quite a few people fell out during the recession,ŌĆØ as their companies let apprentices go. However, the figures over the past decade show that last yearŌĆÖs drop-out rate was part of a wider pattern. And even if this yearŌĆÖs new apprentices have greater staying power, they will not provide short-term relief for an industry that faces a desperate need for more skilled labour now.

There are not enough people to deliver what the government wants, whether thatŌĆÖs housing or infrastructure projects

Chris Jones, BAM

According to the CITBŌĆÖs most recent employersŌĆÖ survey, 21% identified finding suitably skilled staff as their key business challenge, a more than threefold increase on the figure of 6% recorded in 2013. The CITB forecasts that this proportion is only likely to worsen in 2015.

SME contractors confirm that they are feeling the pinch too in terms of skills shortages. A recent survey carried out by the Federation of Master Builders showed that 44% of its members are struggling to employ carpenters and joiners, while 42% report the same problems finding bricklayers. Both figures are up by 2% over the last year. Chris Jones, director of learning and development at Bam, says: ŌĆ£There are not enough people to deliver what the government wants, whether itŌĆÖs housing or infrastructure projects.ŌĆØ

A report, jointly published by the London Chambers of Commerce and KPMG last month, underlines the depth of the looming skills crisis facing the industry. It predicts that the pipeline of work in London and the South-east alone will generate demand for more than 600,000 construction workers by 2017, compared to a total requirement of 430,706 last year. To plug this gap, KPMG estimates that the industry should be training nearly 30,000 new skilled workers each year, just over double the current level of entrant apprentices to the industry.

Richard Threlfall, head of infrastructure and construction at KPMG, believes that the skills shortfall will translate into projects being delayed across the industry, making it harder for developers to seize the moment offered by a return to favourable economic conditions. ŌĆ£It ends up in a series of endless slippages, which eventually becomes a landslide,ŌĆØ he says.

Image problem

However, apprenticeships continue to suffer from an image problem, according to research due to be published next week by think tank Demos. It will show that parents generally think apprenticeships are a great idea, just not for their kids. A survey of parents of teenagers showed that 90% thought that apprenticeships are a good option for school leavers. However just 32% said it was a good idea for their own child. ŌĆ£People like apprenticeships in theory but arenŌĆÖt convinced for their own children,ŌĆØ says Ian Wybron, researcher at Demos.

And construction apprenticeships are seen as less appealing still with just 75% of parents viewing it as an attractive career option. ŌĆ£The construction industry still has progress to make in winning over parents and schools,ŌĆØ says Wybron.

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), which oversees training policy, has made a lot of noise in recent years about reforming apprenticeships as part of a wider drive to improve the economyŌĆÖs skills base. The Labour party has got in on the act too with its leader Ed MilibandŌĆÖs promise last month to boost the number of guaranteed apprenticeships.

Funding shake-up

The governmentŌĆÖs proposals, which were informed by the Richard Review of apprenticeships, start with the well-intentioned principle that firms need to be more closely involved in paying for and framing apprenticeships.

One of BISŌĆÖ criticisms of the current system, under which the CITB arranges training on firmsŌĆÖ behalf, is that companies have little clue about how much apprenticeships cost, and therefore do not value them enough.

People like apprenticeships in theory but arenŌĆÖt convinced for their own children. Construction still has progress to make in winning over parents and schools

Ian Wybron, Demos

However BISŌĆÖ initial proposals, which would have forced employers to pay up front for apprenticeship training and then reclaim a share of the costs from CITB, went down like a lead balloon with the small firms that train the vast majority of construction apprentices.

These micro-businesses that employ 10 people or fewer, which the FMB estimates deliver around two-thirds of construction apprenticeships, were worried that the governmentŌĆÖs scheme would just exacerbate their already acute cash flow headaches.

They also saw little benefit in the governmentŌĆÖs plans to get companies more involved in the shaping of apprenticeships through its Trailblazer initiative, under which firms collaborate on developing tailor-made standards.

The CITBŌĆÖs Econopouly says: ŌĆ£You need to take into account the relative abilities of different types of organisation. Larger companies will have quite sophisticated training resources but itŌĆÖs very difficult for the SMEs that make up 90% of our sector to get involved.ŌĆØ

In response to the backlash from across business, ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° understands that BIS has drawn up a new system of training vouchers, which is due to be launched in the middle of this month. If a company wants to hire an apprentice, it will need to complete a form. On the basis of the details that the firm provides, the government will assess the level of discount it is entitled to. The company will then shop around for a college to provide the training that it wants, paying the difference on the value of the voucher.

Sarah McMonagle, head of external affairs at the FMB, says the latest proposals are a big improvement on the governmentŌĆÖs previous plans, because they mean less cash need change hands. However, she says small builders are still concerned about the extra bureaucracy that the shake-up will entail. ŌĆ£Employers canŌĆÖt give tons of time to get involved in this kind of thing because they have businesses to run. This could really mess things up if they (SMEs) are discouraged from training apprentices.ŌĆØ

Picking up on one of the themes of the Demos report, Econopouly argues that getting schools more engaged with the industry is key to improving apprenticeship start rates.

She says: ŌĆ£We need to get careers advisers thinking more about construction. ItŌĆÖs often not mentioned or in an unfavourable light.ŌĆØ

And itŌĆÖs not just the overall level of apprenticeships that needs to improve but also what is being taught, argues Threlfall, pointing to how the system is currently not delivering enough skills in specialised but high-demand areas like steel fixing.

BamŌĆÖs Jones agrees: ŌĆ£More prefabrication means that construction skills are fundamentally different to what they used to be. For example, we donŌĆÖt need the same number of skilled bricklayers on site, but we need people who can lay blocks.ŌĆØ

For Threlfall, though, while the supply of skills training needs to improve, any boost to apprenticeships wonŌĆÖt address the industryŌĆÖs immediate skills needs. What will, he suggests, is a politically unpalatable but less jaundiced approach to immigration. ŌĆ£For all their scepticism about the flow of labour into the country, politicians must recognise the extent to which this industry is heavily reliant on import of labour if itŌĆÖs to keep expanding at the rate it can.ŌĆØ

YouŌĆÖre hired - how one apprentice got his break

James Skyrme (pictured) was understandably downbeat when a work placement with Birmingham councilŌĆÖs housing department, arranged via the now-defunct Future Jobs Fund scheme, came to an end.

Despite applying for numerous positions, he ended up signing on for two months. Skyrme then registered on Birmingham councilŌĆÖs employment access database and applied for a site operative vacancy with Coleman and Company, the Birmingham-based specialist demolition contractor that Mace has signed up to knock down New Street station.

Just over a year ago, Coleman took on Skyrme to its apprenticeship training programme to become fully qualified as a demolition site operative, the 100th apprentice to be taken on via the Mace supply chain at the New Street project, which is transforming BirminghamŌĆÖs major rail hub.

Many of these apprentices have worked with MaceŌĆÖs socio-economic team, which supports individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds to find employment. And the unemployed school leavers that the Mace team works with often have even less of a work track record than Skyrme.

The teamŌĆÖs remit can extend to phoning the youngstersŌĆÖ homes at 6am to make sure they are out of bed, and providing free canteen meals until the first pay cheque arrives. Those taken on as apprentices under MaceŌĆÖs socio-economic programme tend to be beneficiaries of section 106 agreements, which stipulate that trainee opportunities on projects are earmarked for local unemployed youngsters.

David Rowbotham, head of socio-economics at Mace, says the companyŌĆÖs position as main contractor on significant projects like New Street means it has leverage within its supply chain to achieve such goals.

And the number of apprenticeships delivered at New Street indicates the training opportunities such big, long-term projects can offer, he adds. ŌĆ£It shows what can be done to bring young people in when thereŌĆÖs a big infrastructure project.ŌĆØ

Skyrme, who is 27, has just finished at New Street as demolition work there winds down. However he has now moved to a new project on the other side of Birmingham city centre, where he continues to make progress with Coleman.

No comments yet