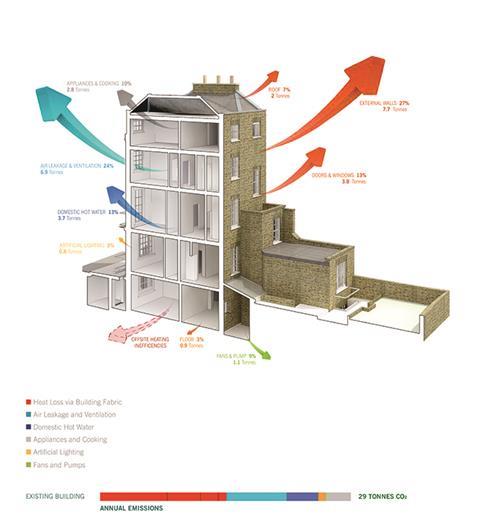

Belgravia is one of LondonÔÇÖs most genteel quarters, but its Georgian homes are among the UKÔÇÖs least energy efficient. Now, David MorleyÔÇÖs BREEAM ÔÇśoutstandingÔÇÖ renovation of a grade II property has shown that heritage doesnÔÇÖt have to mean high emissions

Until very recently, no listed building in the UK had achieved BREEAM ÔÇťoutstandingÔÇŁ certification. And 119 Ebury Street in LondonÔÇÖs Belgravia is the first. The project involves the complete reconstruction, refurbishment and conversion of a four-storey Georgian townhouse into three duplex flats. Despite being located in one of the most affluent neighbourhoods in the country, the house had fallen into an advanced state of structural and cosmetic dilapidation. Like some other properties on the same street, it had also been converted into a rather insalubrious hotel. These factors presented a number of onerous technical challenges that made the projectÔÇÖs impressive sustainability performance even harder to achieve.

Another obvious and severe constraint was the buildingÔÇÖs grade II-listed status. Westminster alone has over 11,000 listed buildings, around 3% of the national figure. Many of these buildings are located within Belgravia and 119 Ebury Street falls within one of the boroughÔÇÖs 56 conservation areas. These heritage considerations placed a clear emphasis on the retention rather than replacement of a building fabric marked by an appalling environmental performance, calling for considerable ingenuity when it came to the buildingÔÇÖs sustainable design.

The house is part of the Grosvenor Estate, one of the countryÔÇÖs largest landowners, whose property includes much of Belgravia and the surrounding areas. Grosvenor has identified the project as a pilot scheme that will be rolled out to other properties across its considerable estate - up to 200 are currently being retrofitted.

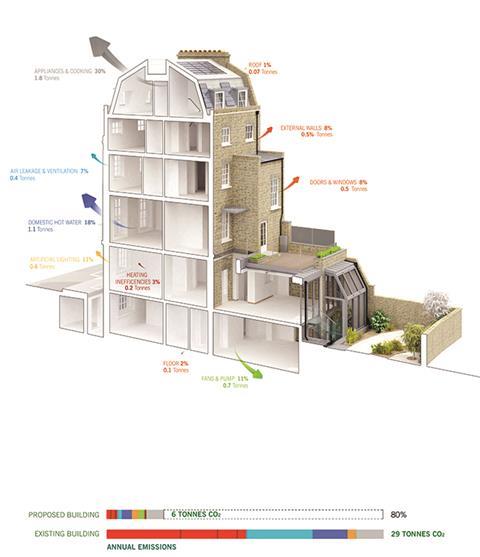

These developments are a key part of GrosvenorÔÇÖs contribution to the governmentÔÇÖs 2050 target of an 80% reduction in operational carbon emissions. Achieving such low emissions within heritage buildings could therefore have national implications for how historic housing stock is retrofitted to satisfy modern environmental standards.

Jennifer Juritz, associate and head of environmental services at architect David Morley, the schemeÔÇÖs designer, identifies a two-pronged approach to the buildingÔÇÖs restoration: ÔÇťUnderstanding whatÔÇÖs key about the heritage aspects of the property and assessing the exact nature of its environmental behaviour and performance.ÔÇŁ This analysis helped to produce a series of design solutions that together realised 119 Ebury StreetÔÇÖs groundbreaking BREEAM score. These are listed below.

Existing fabric upgrade: windows

The sash windows neatly summarise the design paradox that dogged the entire project. On the one hand, they were generally in a poor state with timber mullions worn away and single glazing providing terrible thermal insulation. On the other, they constituted key heritage aspects, the fabric and proportions contributing much to the light and spatial character of the interiors - which is why the statutory authorities insisted on their retention.

This imposition provoked an enormous amount of investigation and consultation.

A full-size window mock-up was built and window mullion profiles were even 3D-printed to satisfy local authority qualms about aesthetic changes.

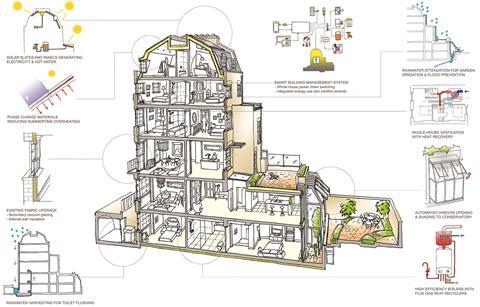

The eventual solution involved the installation of vacuum-glazed secondary Selectaglaze and Pilkington Spacia glazing to improve U-values and help achieve an airtightness level of 3m┬│/hr/m┬▓. Triple-glazed timber frame windows are being installed to new extensions on the ground and lower ground floors. Windows to a new conservatory to the rear have also been fitted with automated window opening and shading.

Existing fabric upgrade: walls

Walls too had been a constant source of heat loss and comprised a broad set of historic conditions, which included solid-brick uninsulated external walls and worn lime-plastered timber internal partitions.

Accordingly, a variety of upgrade solutions were selected. A combination of aerogel and vapour-permeable solid internal wall insulation is being installed across the house in order to minimise the risk of interstitial condensation and to improve U-values of retained solid walls, as well as achieving the lowest possible U-values for new elements - 0.15w/m┬▓/K has been targeted for the walls and a newly built Mansard roof. Insulation includes Procter Spacetherm and Remmers IQTherm. Phase-change materials were also applied to roof areas to reduce summertime overheating.

Solar panels and heat recovery

Solar energy makes a big contribution to the heating, electricity and hot water supply of the refurbished building. Solar panels are a contentious addition in any conservation area and this was even more the case at 119 Ebury Street with its celebrated and historic Belgravia setting. The result is an innovative solar strategy that includes three types of solar panel.

A solar thermal unit is discreetly mounted to a closet wing to the rear of the property. This supports a space heating and hot water strategy comprising two combi-boilers with flue-gas heat recovery and one condensing system boiler. All units are low-NOx, high-efficiency Vaillant systems with flue gas heat recyclers.

Further on-site generation is located on the roof facing to the rear and comprises six 330W monocrystalline panels with a peak power of 2.08kWp. However, for the front-facing roof, the most historically sensitive part of the roofscape, 1.40kWp of solar slates have been installed, merging visually with the surrounding slate tiles. The use of these solar strategies enables the development to achieve a post-refurbishment SAP rating of 88, with 100 representing zero energy cost, and primary energy demand of 68.1 kWh/m2/year.

A mechanical ventilation and heat recovery system, in the form of Itho Advance and Zehnder Comfoair units, has also been adopted. This sucks in cold external air, which is then warmed by extracted air from bathroom and kitchen areas to provide internal background ventilation. The careful insertion of the ductwork into the buildingÔÇÖs historic fabric also presented logistical challenges.

Collected rainwater is used in various ways in the property to maximise energy efficiency. The sanitaryware strategy has been optimised

to meet the BREEAM ÔÇťoutstandingÔÇŁ requirement of less than 96 litres per person, per day. This is supplemented by a rainwater harvesting system that provides water for toilet flushing.

The system also provides stormwater attenuation, which helps to prevent flooding and irrigates the rear garden.

║┌Â┤╔šă° management system

A key component of the refurbishment from both a sustainability point of view and GrosvenorÔÇÖs strategic property maintenance of the entire estate will be the installation of a smart building management system (BMS). This will also form a crucial part of GrosvenorÔÇÖs post-occupation evaluation assessment and will thereby heavily inform the composition of other residential refurbishments within its portfolio.

A sophisticated BMS system will incorporate whole-house power-down switching, whereby a single switch can shut off power to all appliances and circuits within the house other than those that require constant energy (such as fridges). Integrated energy use and comfort controls will also empower users to take responsibility for how much energy they use.

In terms of post-occupancy evaluation, the BMS will also collate a prodigious amount of data. This will include energy-use comparisons, temperature recordings, server data as well as non-technical information such as resident feedback.

Project team

Client Grosvenor

Contractor Grangewood Builders

Architect David Morley Architects

║┌Â┤╔šă° services Edward Pearce Consulting Engineers

Structural engineer Hurst, Peirce & Malcolm

BREEAM and energy consultant Eight Associates

QS and contract administrator Thompson Cole

Click on the diagram above to enlarge

No comments yet