Closer integration of the multifaceted services within health and social care is critical in developing a sustainable health system. Mark Robinson of Aecom and Marc Levinson of Murphy Philipps Architects report on how primary care is at the forefront of this challenge and how construction can respond

Jump to 11 / Cost Model:

01 / Introduction

The NHS is celebrating 70 years and is considered to be one of the best healthcare systems in the world. The NHS has always gained significant public attention and support, heightened during these challenging times. With primary care as the front door of the NHS, where patients are likely to receive their first interaction, this service needs to continually adapt to support the future direction of the NHS.

Primary care is mainly provided by general practitioners (GPs), community pharmacists, dentists and opticians. There are regional differences across the UK. On behalf of NHS England, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) review, plan and procure primary care services and are responsible for delivery, quality, financial resources and public participation. The principle is that this care should be delivered outside hospitals wherever possible, with clinical pathways designed with this in mind.

Prominent focus has been on expanding the health offering from within the primary care setting in order to reduce demand on hospital services, with examples of improved patient experience.

With the further incorporation of social care, facilities must allow for both adaptable accommodation and technology to create an efficient response in bringing together such far-reaching services. These include community health, hospital services, mental health, social services, leisure, education, housing, transport, voluntary sector and other organisations and services.

02 / Purpose

Then

Before the 20th century, family doctors generally worked independently from any other healthcare provider, serving local, paying patients. In 1920 the Dawson report on the provision of medical and allied services initiated the steps towards a national strategy for healthcare, proposing a unified network of primary and secondary healthcare centres in accessible community locations.

This strategy was reinforced in 1946 by the National Health Service Act, giving local authorities responsibility for constructing health centres to accommodate their nurses, health visitors and dentists, and to rent space to GPs.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a number of initiatives for enlarging and improving primary care, together with financial incentives and funding mechanisms. These included the white papers Promoting Better Health (1987) and Primary Care: Delivering the Future (1996), as well as the National Health Service and Community Care Act in 1990.

These initiatives provided a formal commitment to provide healthcare within the community. Co-locating a number of services within a single building was seen as critical in ensuring that different healthcare professions would provide an integrated service.

The NHS (Primary Care) Act 1997 allowed for the establishment of additional working contracts for GPs in order to allow more flexibility for practices to work in different ways and to develop specific services for local needs.

Now

Current trends include the co-location of non-NHS community and voluntary services within healthcare facilities. This addresses the drive to provide more integrated and cohesive services for the local population in a convenient setting.

By considering all local services and consolidating them, this provides an opportunity to develop or dispose of surplus land, thereby providing additional funding to contribute to the replacement of outdated or non-compliant facilities.

Programmes such as One Public Estate, set up in 2013, seek to consolidate public services in a more efficient way. Increasing the number of stakeholders within a project is not without its challenges and it is critical that specific procurement routes and associated contractual agreements are established early to enable these projects to proceed.

Primary care facilities play a key role in the hub and spoke model for health service delivery. The hub usually consists of a major acute hospital housing specialist clinical activities such as an accident and emergency department, operating theatre suite and a large number of inpatient beds. The spokes include a variety of sizes of healthcare facilities, ranging from individual GP practices to large health centres and community hospitals.

No building within this model can be considered in isolation from the others that form part of the same network, and the briefing documentation will reflect this. Practical considerations, such as shared facilities management teams or the movement of staff between the sites, will impact on the design and operation of each facility.

The future

It is becoming ever more likely that primary care facilities will actually contract in size. GP triage and consultations are increasingly being undertaken over the telephone, and technological developments are leading to the ever-decreasing size of medical equipment, which reduces the need for large rooms and suites to accommodate items such as diagnostic equipment.

The health market is of such a considerable size that technological companies will continue to invest in it heavily. A patient gaining digital access to health records is just a first step and is linked with a rise in a proactive approach to health among consumers. Technological growth will support better accuracy in the collection and accessibility of health data, taking it beyond the current model of fitness tracker to record body movement, heart rate, blood pressure, quality of sleep and calories burned. GPs are likely in the future to have direct access to such personalised data, supporting preventive measures against ill health.

03 / Funding

Funding from public health organisations requires the approval of a business case, which needs to be robust and sustainable, allow measurable benefits and demonstrate value for money. This is irrespective of the type of work – whether to resolve compliance issues, supporting reduction in operational costs or implementing wider healthcare strategic objectives.

The NHS has backed the implementation of an increased level of primary care service through application to capital funds, such as the Prime Minister’s GP Access Fund and the Estates and Technology Transformation Fund (Primary Care), with the aims of addressing:

- Backlog maintenance/fitness for purpose

- Increasing utilisation (refurbishment/extension and new developments)

- Upgrading infrastructure, information technology and equipment

- A growing workforce and initiatives such as changes in the model of care.

Publication of the General Practice Forward View added further direction to recognise the importance of “convenient access to care, a stronger focus on population health and prevention, more GPs and a wider range of practice staff, operating in more modern buildings, and better integrated with community and preventive services, hospital specialists and mental health care”. With continued public support, an NHS tax may come into being.

Other funding options include an NHS local initiative finance trust (LIFT) or a private-public partnership (PPP). Community Health Partnerships (CHP), owned by the Department for Health, typically has a 40% shareholding – though in some cases sharing this with a local authority – and the private sector 60%. It has assisted in the creation of number of facilities supporting primary and community services. CHP’s upcoming Project Phoenix will add further opportunity for the private sector to support the wider NHS estate transformation programme, with a new PPP model supporting NHS infrastructure, planning and investment that seeks to complement LIFT.

04 / Design principles

Guidance

Design and technical standards compliance is set out in Department of Health publications such as health building notes (HBNs) and health technical memoranda (HTMs). While they do not dictate overall building design, they include information on space standards, accommodation requirements and environmental targets.

Primary care design guidance (in the form of HBN 11-01) outlines the requirement to provide flexible and adaptable accommodation. This usually manifests itself in the provision of generic rooms sized to accommodate a wide range of activities. This allows a degree of short-term flexibility whereby different services can be provided in a single room over the course of a week, where a particular service does not require a permanent space – for example, visiting physiotherapists at a GP practice.

Stakeholder engagement

There are likely to be separate organisations that own, run and use the building. All but the smallest primary care buildings house several different providers delivering various services to patients. This can complicate the process of providing efficient and cost-effective facilities. Meeting with representatives of each service at any early stage of the design can smooth this process, although it ultimately relies on ongoing building management of the space.

Build area

During the processes that precede building design – such as initial costing and site selection – an overall building area needs to be estimated. Generally this is generated from a schedule of accommodation of the required rooms, with a variety of percentage allowances for circulation, engineering and other spaces. The Department of Health and Social Care guidance provides these percentages based on the nature of the healthcare facility. The design team must ensure this efficiency is incorporated in the emerging design proposals.

Transport

The past decade has seen an increasing trend in the numbers of patients travelling to and from health facilities. A balance needs to be found between ensuring the site provides sufficient levels of parking – taking into account any measures to encourage alternative modes of transport – while avoiding unmitigated adverse impacts on the local highway network. Parking provision should complement rather than be an alternative to improvements to non-car accessibility.

Future proofing

There are a number of key strategies and innovative approaches to ensure the longevity of healthcare facilities. Traditionally this has been through the identification of physical space for horizontal or vertical expansion of the building. This was based on the assumption that buildings would need to grow and that this would be both affordable and acceptable to the local planning authority. Providing initial infrastructure to enable future expansion, such as using a structural strategy that would allow addition of a further building storey, or ventilation systems that can support additional treatment spaces, bring additional cost that may be difficult to justify in respect of current clinical needs.

05 / Form

A concrete frame structure with flat slabs, free of down-stand beams, is often preferred to allow the unrestricted routing of services. The mass of the slabs helps to control vibrations and also assists in achieving the required acoustic separation between floors. Reinforced concrete also has inherent fire resistance.

A steel frame building will typically have down-stand beams, which need careful co-ordination with service routes and a deeper overall floor depth compared with a concrete flat slab. This increases overall building height, sometimes with planning impact.

Steelwork needs separate fire protection through the application of intumescent paint or by boxing out with a fire-resistant board.

The time required on site for steel-framed construction is generally less than concrete, because the steel elements are prefabricated. The slab elements supported on the steelwork are also often prefabricated and simply grouted together on site.

Creating long, column-free areas at entrances and around atriums is more straightforward in steelwork, as is making future alterations to the structure. Steel frames are lighter and this can be an advantage when considering constructing additional floors on top of existing buildings.

Modern methods of construction (MMC) will seek to maximise the amount of offsite assembly through the use of a volumetric system. This approach offers shorter construction periods, fewer defects and a reduction in energy and waste and is considered safer. The housing sector particularly has seen huge advances using MMC.

Considering the relatively small scale of a single primary care facility, MMC design considerations must be integrated and obtain stakeholder buy-in from the outset in seeking to achieve quality and time benefits. These design considerations include standardising modular bays within the floor plan while acknowledging site logistics, a high proportion of drainage points to plan early, and an alternative foundation design with increased point loads.

On urban sites with past development, ground conditions may be poor and substantial foundations such as piles may be required even for low-rise buildings. Understanding the site constraints is key to developing an appropriate foundation solution and minimising construction risk. A detailed ground geology investigation will establish the presence of any contamination and confirm the extent of below-ground obstructions. Surveys are also likely to be needed to cover aspects such as the location and condition of existing drainage runs, the position of existing utilities pipes and cables and the risk of encountering unexploded bombs, archaeological remains or rare species of animals or plants.

06 / Services

�ڶ����� services have an increased complexity as a result of the differing functional areas and the associated HBN and HTM design guidelines, �ڶ����� Regulations (particularly Part L) and local government improvement measures.

The facility will require extensive sanitary outlets, disposal and water distribution. The typical low-rise design and number of individual rooms requiring public health services often mean a high level of underground drainage connections and extensive water distribution across individual floors. Any specialist treatment areas are likely to have dedicated public health and water treatment systems.

Natural ventilation, a first consideration within HTM 03-01, cannot be guaranteed to provide a minimum air change rate at all times as it is inherently variable. Certain health services require a heightened room air change rate, but restrictions associated with noise infiltration and security will limit openable areas. Fresh air mechanical systems can be provided in part for mixed-mode ventilation or a fully supported system (a sealed building). Designers should be aware that the current HTM 03-01 is now 10 years old and an update to the edition is being planned.

The design temperature criterion for patient areas is that it should be above 28ºC for no more than 50 hours. In many towns and cities, the outside temperature used in the CIBSE design weather file exceeds this temperature criterion in the first instance, meaning natural ventilation on its own is unlikely to be possible without supplemental cooling or derogation – room planning and building orientation should be an early design consideration. Cooling will generally be provided via locally controlled heat pump systems with either ducted FCUs or ceiling mounted cassette units. Where there are areas of natural ventilation or a mixed-mode system, any cooling can be interlocked with the windows or facade vents.

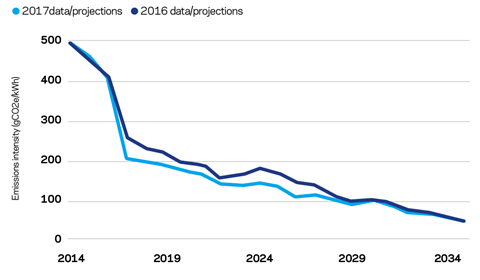

Heating is generally provided by low-nox gas-fired condensing boiler plant and distributed to either radiant panels or underfloor heating, depending on the functional area and whether the space is naturally or mechanically ventilated. Alternatively, an area may be heated via a heat pump system if installed. Strategic consideration of reducing carbon emissions beyond building regulations will need to be considered in the design. It has been forecast that by 2020 the carbon emissions from using grid electricity will be lower than using natural gas. This will bring forward further design discussions around electrical heating, such as the inclusion of photovoltaics with either air source or ground source heating.

The incoming electrical supply will be delivered at low voltage with each clinical department often metered and energy monitored individually. Permanent standby generation is not usually provided other than via local uninterruptible power supply (UPS) units serving IT systems. Any specialist treatment areas will be served by dedicated isolated power supply and UPS systems. However, as primary health continues to integrate with secondary services, agreeing clinical risk grades for the accommodation is important to avoid over- or under-provision.

CCTV coverage will be provided to the perimeter and external access points along with key circulation/waiting areas. Access control will be installed at all external access points and the interfaces between public and staff areas. A nurse call/panic alarm system will be distributed to all consulting and treatment areas with twin call points often specified.

Extensive IT distribution will be provided throughout the building from a central server and supplemented with local communications cupboards.

�ڶ����� management system controls are not complex but will offer sufficient control and monitoring facilities to allow the building to function in an energy-efficient manner without permanent on-site FM supervision. Any occupancy monitoring systems can be included within the BMS or via a standalone wifi system to support user utilisation assessment.

07 / Sustainability

Primary care developments can be assessed under the sustainability assessment method BREEAM. This evaluates schemes against environmental performance benchmarks – and has a section on health and wellbeing that covers daylight levels, overheating, air quality and acoustics, all of great benefit to users of healthcare facilities. Evaluation culminates in a certificate rating from Pass to Outstanding.

To ensure that securing good ratings does not get easier, and therefore devalued, over time as standard construction practices and technology improve, the BRE periodically updates the methodology. The newest, March 2018 iteration also marks the closure of the 2014 scheme to new registrations.

| BREEAM2008 | BREEAM2011 | BREEAM2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pass |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

Good |

15 |

1 |

0 |

|

Very good |

115 |

37 |

10 |

|

Excellent |

86 |

20 |

2 |

|

Outstanding |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Since 2008 about 290 healthcare developments have completed the BREEAM assessment process

The BRE’s Green Book Live database shows that since 2008 about 680 healthcare developments – a category covering all healthcare uses – have undertaken assessment under BREEAM, with about 290 completing the process and achieving final certification.

BREEAM 2018 introduces new credits for predictive operational energy consumption (which is unregulated energy, whereas earlier schemes mainly covered regulated energy) and use of lifecycle assessment software to assess the full lifecycle impacts (such as embodied carbon). These additions, which specifically focus on operational issues and performance, will be well received by occupiers of all developments, especially primary care facilities.

08 / Lifecycle

Operators across all health and care facilities continue to make difficult decisions on where to spend their budgets. In terms of lifecycle expenditure, such decisions are focused on ensuring the ability to continue delivering services and patient care.

The requirement for flexibility, recognising the greater breadth of services to be provided, means the design process needs to pay special attention to how spaces can be transformed with limited impact on operating costs and future capital replacement costs.

More convenient patient appointment times will result in longer operational periods, meaning systems must be designed to allow maintenance through centralised points in order not to impede day-to-day activities. To ensure maximum flexibility, building design will need to incorporate sufficient spare capacity of core systems.

Rising utility costs bring the need to consider more energy-efficient systems, such as different types of lighting systems and different approaches to heat and power for the facilities. This is leading some organisations to undertake whole-life cost analysis of systems and products to make a business case for “spend to save” initiatives, which offset the initial capital costs through reduced operational costs.

09 / Fiscal incentives

Depending on the nature of the developments, and the tax status of the entities incurring the expenditure, there can be opportunities to benefit from tax reliefs in the form of land remediation relief (LRR) and capital allowances.

LRR is a 150% first-year tax relief that is available to reduce the taxable profits of both developers and investors incurring qualifying expenditure on remediating contaminated land and buildings.

In order to be entitled to claim LRR, the vehicle incurring the expenditure must be within the scope of UK corporation tax and satisfy various conditions in accordance with UK tax legislation. Loss-making entities can also potentially avail of this relief through claiming tax credits.

Capital allowances are another tax relief that can reduce the tax liability of the profits of investors subject to either UK corporation tax or UK income tax. Capital allowances are available on expenditure incurred on qualifying plant and machinery assets in accordance with UK tax legislation and case law, and can often apply to a significant proportion of the total development cost.

Proactive early advice can optimise the tax reliefs available on a scheme, enabling them to be factored into a cost model or appraisal, and ultimately substantially mitigate the costs that are involved.

10 / About the cost model

The cost model is for a three-storey new-build primary care health centre, for GPs, community nurses, midwifery services, mental health services, social services and support services; both internal and external finishes are to a good quality.

The building in the cost study contains a gross floor area of 2,500m2 and is located in Greater London. Costs included are based upon 2Q 2018 and include for group 1 and fitting of group 2 furniture, fixtures and equipment, but exclude external works, utilities, design/construction/client contingency, professional fees, surveys and VAT.

The rates may need to be adjusted to account for specification, site conditions, procurement route and programme.

11 / Cost model

To view the cost model, click on the PDF below.

Downloads

Cost model primary care

PDF, Size 54.32 kb

Postscript

Acknowledgements: With thanks to Andrew Rowland, James Mowll, Simon McLaughlin, Stephen Baker, Ralph Stapleton, Phil Mackintosh and Colin Page.

No comments yet