Faithful + Gould project manager Jane Foulkes was a BIM sceptic until she was faced with a complex prison design project and a three-month deadlineŌĆ”

Jane Foulkes is not your typical BIM early adopter. Indeed, she admits that before she was thrust into the role of project managing the first government scheme to be entirely delivered using BIM, she knew very little about it. ŌĆ£I had no experience of BIM whatsoever - I hadnŌĆÖt used it on any previous projects,ŌĆØ she says.

Just 12 months later, she probably knows more about BIM than 99% of her peers, and her initial scepticism has given way to a strong belief in its potential to improve quality and efficiency across the industry. This is perhaps what makes Foulkes such a good ambassador for BIM, especially in a sector that is not exactly renowned for embracing new technologies. She will now be working for the UK BIM Task Group and the Construction Industry Council as a BIM implementation support officer, one of five who will be helping Whitehall departments to implement the technology by 2016.

An associate director at Faithful + Gould, Foulkes originally qualified as an architect and worked for healthcare clients and the Oxford and Cambridge colleges, before a ŌĆ£midlife dissatisfactionŌĆØ led her to enrol for a masters degree in construction and project management. For the last five years, she has headed a team responsible for delivering more than 30 new-build and refurbishment projects for the Ministry of Justice (MoJ).

It was this department that was chosen as a trailblazer, the first to use fully collaborative level 2 BIM on a pilot ŌĆ£early adopterŌĆØ project at Cookham Wood, a young offendersŌĆÖ institution in Kent, where a 180-cell extension is now on site. The MoJ already uses ŌĆ£lean programmingŌĆØ to minimise waste, but it was hoped that BIM would help to achieve a further 20% saving on all future projects. The BIM process would also contribute to building a library of standard COBie (Construction Operations ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° Information Exchange) data - a way of capturing all the information about a project. This could be used to inform future MoJ project designs, and for facilities management throughout the buildingŌĆÖs life.

But it was a steep learning curve - made even steeper by the fact that there were just three months to complete the design and get it out to tender. The project had been on hold for six months, and when it went live again in January 2012, the original March deadline still stood.

No time to waste

FoulkesŌĆÖ initial reaction to this was one of total disbelief - the timescale would be tight enough without having to implement a new process. But there was no time to spare, so she just got on with it. ŌĆ£I was not going to let my project be overtaken by BIM. I had timescales to deliver to and an end-of-year spend to meet, and these were the project drivers. After a time, however, I realised BIM should actually make the outcomes I had to deliver more straightforward, and more reliable for my clients.ŌĆØ

It became both a practical and an intellectual exercise, with everyone pitching in

It helped that Foulkes was working with an experienced project team who knew each other well, and were spurred on by the scale of the challenge. ŌĆ£We spent a lot of time asking questions, surmising things and generally pushing in the same direction,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£It became both a practical and an intellectual exercise with everyone pitching in to make it work.ŌĆØ

The first step was to develop the Client Requirements Document - also known as the Employers Information Requirements - which basically integrates how the project team should use BIM into the existing clientŌĆÖs brief. As this was the first project in the UK to be tendered in this way, these documents will provide a foundation for later projects. ŌĆ£We had to define the level of detail, and exactly what the model had to contain at every stage,ŌĆØ explains Foulkes. ŌĆ£Every project stage in 2D has a set of deliverables, which become more and more defined, refined and complete. With BIM, all of that needs to be defined all the way through the project. You also need to understand what the client requires to enable financial sign-off at each stage.ŌĆØ

The next step was to adapt the MoJŌĆÖs procurement process and tender documents to ensure the resulting model would be fit for purpose, and to assess the BIM capability of tenderers. Contract amendments were considered, to change the scope of consultancy services and reflect possible changes in intellectual property, but in the end very few were required.

The designers had already used BIM on a previous project, but Faithful + Gould had neither the software nor computers powerful enough to deal with the models - and in any case, there wouldnŌĆÖt have been time to train Foulkes to use it all. In fact, for a level 2 project - in which all project data is shared electronically but each discipline creates separate models, which are checked for clashes - this wasnŌĆÖt necessary. ŌĆ£I just needed to be able to monitor the progress of the model and see the design as it developed.ŌĆØ

It was decided that every Friday the design team would carry out clash detection and upload their latest models to the projectŌĆÖs secure extranet, as well as a set of 2D cuts in PDF form that could be viewed by Foulkes and the client. This not only led to much better communication among the team, but contributed to meeting the deadline two weeks early. ŌĆ£I think it drove the programme a bit harder, because it required everyone to work more closely together, and we had to resolve issues earlier.ŌĆØ

Real exhilaration

For the client, the 3D models brought the project to life far more vividly than 2D drawings could have done. ŌĆ£There was a moment of real exhilaration when we showed a fly-through to the prison governor and her staff,ŌĆØ Foulkes recalls. ŌĆ£It made it very transparent for them - they could see exactly what they were getting and could immediately spot potential issues.ŌĆØ

The client could see exactly what they were getting and spot potential issues

For example, the prison staff had requested glazed screens instead of gates, but when they saw the model, they realised this would prevent audible contact between two areas of the houseblock, so they reverted to gates. ŌĆ£In the 2D drawings, the screens would be shown as parallel lines, but you wouldnŌĆÖt see what they were made of. In the BIM, they appeared as a solid piece of glass so they could immediately identify the problem.ŌĆØ Terry Stocks, head of project delivery at the MoJ, has stated that the early capture of changes has already saved ┬Ż800,000 on the project.

FoulkesŌĆÖ new role will involve spending two days a week at the Education Funding Agency helping project teams to reap the same benefits on their own early-adopter projects. While there will be technological barriers, she believes the supply chain will resolve those. Her bigger task will be managing the change. ŌĆ£When people are not aware of the benefits, they are reluctant to do things outside and beyond what they normally do. We need to communicate the benefits well enough and create enthusiasm. ItŌĆÖs about identifying who really wants to do it and enabling them, and encouraging and cajoling the people sitting around the sides.ŌĆØ

As a former sidelines-sitter herself, she should be well equipped to convince them. ŌĆ£If a sceptic like me can convert,ŌĆØ she points out, ŌĆ£the future is bright.ŌĆØ

BIM: Level by level

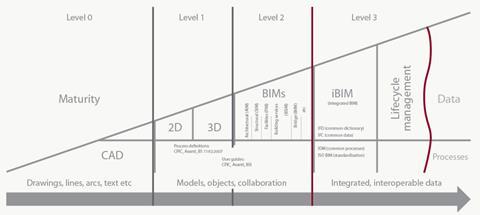

By 2016, all government projects must be delivered using level 2 BIM, as shown in this maturity model taken from the governmentŌĆÖs BIM Strategy Paper. Level 0 is defined as unmanaged CAD, probably 2D, with data exchanged using paper (or electronic paper). Level 1 is managed 2D or 3D CAD using BS1192:2007, with a common data environment but finance and cost information held in separate packages. Level 2 is a managed 3D environment, still held in separate BIM tools by each discipline with attached data, and commercial data managed by an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system. Level 3 is a fully open process with web-enabled data integration, managed with a collaborative model server.

No comments yet