A survey for ∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯‚Äôs Sustainability White Paper suggests that occupants find new buildings only marginally more efficient than older ones. Are their elaborate energy-slashing systems just too complicated to operate?

When we buy something new, we do so because we expect it to be better than something second hand. However, when it comes to energy efficiency in buildings, research by ∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯ published this week indicates that this may not always be the case.

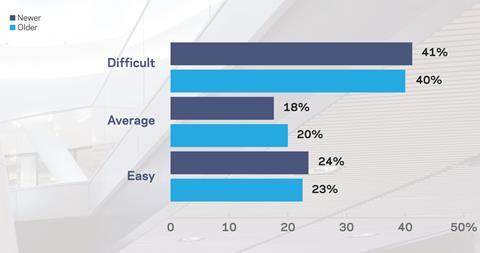

More than 250 construction professionals were surveyed for ∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯‚Äôs Sustainability White Paper, to be released on Tuesday, 20 March. When occupiers of non-residential buildings were asked how efficient their buildings were on a five-point scale, new buildings scored only slightly better than older ones. A total of 27% of occupiers of buildings older than five years rated their energy efficiency as above average, compared to 35% of occupiers of newer buildings. More worryingly, 41% of new building occupiers said their buildings were difficult to ‚Äúoptimise‚Äù for energy use, marginally higher than the 40% of respondents that said the same about older buildings.

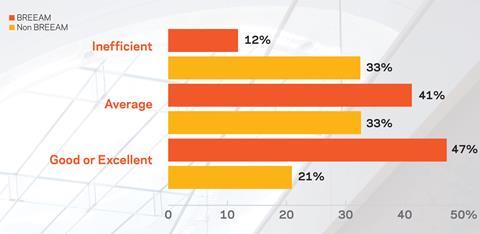

It is not because it cannot be done. When occupiers of buildings that had received a positive rating under BREEAM were asked to rate the efficiency of their buildings, 47% said they were above average while only 21% of occupiers of non-BREEAM rated buildings said the same. These findings come as the Department for Education is considering abandoning BREEAM standards for new school buildings, with ministers thought to believe the process to be too costly and bureaucratic.

So, are new buildings failing to perform substantially better than old ones? And if so, why?

Technical difficulties

The answer may not be to do with the design or construction quality of the building. Jonathan Garret, group head of environment at contractor Balfour Beatty, says: “A modern building will have better insulation because it’s required. All things being equal you should still get a better performance.”

Patrick Brown, assistant director for sustainability at the British Property Federation (BPF), says under-performance is often due to the owner not understanding the building or having difficulties managing its performance alongside tenants. “Too often the owner is taking action on their own on common services but he cannot get the tenants to co-operate with him or with each other,” says Brown.

John Tebbit, deputy chief executive of the Construction Products Association (CPA), argues that the problems in building management are worse in newer buildings, and arise from the complexity of the systems used.

∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯‚Äôs results give some credence to Brown and Tebbit‚Äôs observations. When asked how easy it was to optimise the performance of their buildings, 24% of new building occupants rated their building above average compared with almost exactly the same - 23% - for older buildings. While you might expect a leaky older building to be difficult to optimise, a newer one should be easier. However, all too often complex systems get in the way of this.

Certainly that has been the experience of Cardiff Metropolitan University since it built its new management school building. David Benson, director of estates and facilities, says: “If we could have put the building up and walked away from it, it would have been fantastic.” But that didn’t happen. He says he has spent a lot of time over the past year working out kinks in the building’s systems.

And despite the overall positive findings, Benson’s experience shows getting a BREEAM certification - the building was awarded Excellent - doesn’t always help. He says BREEAM forced him to install much of the technology now giving him trouble, such as heat exchangers, because of the need to make up points that the building lost in other areas beyond his control.

The draft 2013 Part L regulations, which govern the energy consumption of buildings, are taking a step towards simplification by forcing developers to meet a fabric energy efficiency standard as well as overall carbon reduction target, which may encourage developers to build simpler designs.

The CPA’s Tebbit suggests that it is possible the industry has reached a point where improving building services will no longer deliver jumps in building efficiency, and that designs for reducing energy use that concentrate on the fabric first, such as the German standard Passivhaus, will come to the fore. “Passivhaus is a relatively simple design system because you have taken everything out,” he says.

Paul Edwards, head of sustainability for developer Hammerson, agrees that greater simplicity is desirable, but also warns that this might throw up new problems: “One of the problems you have got with the new Part L standards is that you are going to end up overheating everything if you set a standard for the thermal performance of buildings.”

Becoming better tenants

∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯‚Äôs findings may simply reflect differing expectations, argues Richard Kauntze, chief executive of the British Council for Offices. ‚ÄúI think in the same way that cars are made ever better,‚Äù he says, ‚Äúyou get into this zone where you expect improved efficiency and you might be disappointed if it doesn‚Äôt deliver something whizzy.‚Äù

But others suggest that the answer may lie with tenants. The BPF’s Brown says that often commercial buildings are not used in the way intended because tenants make changes which can lessen the building’s efficiency. He says this is especially the case with speculative buildings because they are not built with a particular tenant in mind.

In a grim irony, there may be some cause for hope here in the fact that the levels of speculative building have been hit so hard by the recession. Mat Oakley, director of commercial research at property agent Savills, says: “Nationally, speculative development is at its lowest ever level… outside London … there’s virtually no speculative office or retail schemes planned for the next five years.”

Hammerson’s Edwards says the biggest factor missing from the drive for greater energy efficiency is better information for tenants. “It’s very difficult to compare two buildings on energy. We have Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) but the government has not yet rolled out Display Energy Certificates (DECs). If you are a tenant and you want an energy-efficient building, it’s very difficult for you to describe that at the moment or for the landlord to provide it.”

Regardless of whether the solution to better performance across the buildings is improved information for tenants, less complex systems, simpler design or managing expectations, it seems likely the construction industry will need to have greater involvement in their completed buildings if it is to substantiate claims about energy efficiency.

How efficient is your building in terms of energy use?

How easy has the building been to optimise?

∫⁄∂¥…Á«¯s‚Äô Sustainability White Paper includes:

- Full analysis of the impact of changing government policy on clients and developers

- In-depth examination of the business case for investing in sustainable buildings

- Survey of more than 300 specifiers showing what matters to them - enabling manufacturers to target resources to win work

- Extensive post occupancy survey revealing occupiers’ attitudes towards building performance and post-handover support from construction teams

- The top performing clients, consultants and contractors based on BREEAM ratings

- Exclusive cost information on the impact of the proposed Part L changes from Aecom

To order a copy go to

No comments yet