The industry needs to address its structure before the skills gap can be bridged

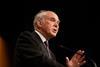

Business secretary Vince Cable was right to identify skills as the major challenge to the UK construction industry in his keynote to the Government Construction Summit this week. He described the tale of lost construction skills from the past recession as a “horror story”, and no one’s going to argue with him.

Over 350,000 staff lost, the volume of apprentices cut by a third, and an industry divided into thousands of subcontracted specialisms in a bid to avoid main contractors sitting with the “liability” of an expensive workforce on their books: it doesn’t make for a comforting story.

All of this leaves the UK with a big problem when it comes to growth. As Cable said, the last thing anyone wants is for the current construction output growth to “come to a shuddering halt because of a lack of skilled people.”

The construction industry has to put its hands up here - the subcontracting business model most of the industry works by means main contractors do not put a premium on recruiting, training and holding on to skilled technical staff. The low margins in the sector mean that spending money on training, as on R&D, is too often regarded as a luxury for the boom time, not a necessity of doing business.

For many it is enough to simply grumble about the CITB levy (often with good reason) and then get on with the day job. Cable’s pledge to help reform apprenticeships funding is welcome, but it is unclear what it means, with the CITB’s new chief executive this week saying he is not able to say how it will work.

However, when Cable calls for the industry to look at its structure, it has to be coupled with a real understanding within government about why the industry works as it does. Without that understanding there is no chance of providing the help needed to change it.

The construction industry moved to a subcontracting model in the seventies and eighties during recessions in which large (and sometimes militant) labour forces became a liability to companies as work dried up. With no guarantee of a pipeline of contracts, construction firms took the view they couldn’t have thousands of employees on their books.

This uncertainty remains a huge problem, with most contractors feeling the recent recession would have seen a far greater number of corporate casualties had they retained big workforces.

The obvious way to combat this, then, is by giving the construction industry a greater degree of certainty over future workloads - something that has been the driver for the government to produce its construction pipelines (hosted, by the way, on �ڶ�����’s website). This is good progress. However, as well as identifying projects, the industry has to know that projects in the pipeline won’t be unexpectedly delayed, cancelled, retendered, reduced or expanded at any moment. The government has a long way to go on this front.

And the industry also has a right to expect procurement to be handled in a way that promotes collaboration - after all, no one is a more experienced client (in theory) than the government. But the glut of legal action over government tenders suggests - while one shouldn’t pre-judge the outcome of challenges - that there is a long way to go here too.

However, the carping shouldn’t be overdone. The government is, after all, a customer of the industry, accounting for around £30bn of work in 2013, and the customer is always right. But before bemoaning the sector the government should make sure it is helping, through its actions, the construction industry to deliver the outcomes it desires.

Joey Gardiner, deputy editor

No comments yet