From the outside it looks like a modern fortress but inside, Shakespeare North Playhouse, the brainchild of Knowsley council, is all Tudor come Jacobean drama ŌĆō with just a touch of Ken Dodd

Like with fast railways, financial services and film studios, the North is missing out ŌĆō this time on dedicated Shakespearean theatres. London has the Globe, a replica of an Elizabethan theatre, and the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, which is a replica of a Jacobean one. The Midlands has Stratford-upon-AvonŌĆÖs Royal Shakespeare Theatre, home of the Royal Shakespeare Company, with an auditorium that is a modern interpretation of a Shakespearian-era theatre.

Now the North is finally getting its very own Tudor replica to address this imbalance. Appropriately, it is called Shakespeare North Playhouse and has been built in a modest town called Prescot, 10 miles from LiverpoolŌĆÖs waterfront.

Why build such a significant theatre in a small town when, in true northern tradition, there is only one slow train an hour to Liverpool? The answer is a combination of historical precedent ŌĆō there is evidence of a long-vanished Elizabethan theatre in Prescot ŌĆō and an enterprising council that set about levelling up Prescot long before Boris Johnson politicised the term.

This combination has produced a unique building with a historically referenced, traditionally constructed Tudor-come-Jacobean auditorium at its centre embraced by a modern ŌĆ£wrap-aroundŌĆØ which houses foyers, a bar, a modern studio space and education facilities. Externally the building is modern with no hint of its historic heart, unlike its Southern cousins which wear their historic origins on their sleeve.

What also distinguishes this building from the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and to some extent the Globe is that there was no evidence to suggest what the original Prescot theatre would have looked like. How does one go about building a replica of a historic theatre when no plans exist, and it has to double up as the saviour of a once prosperous industrial town?

The idea to build a Shakespearean theatre in Prescot germinated from conversations between Nicholas Helm, an architect specialising in theatres, and Richard Wilson, a Shakespearean academic. They established that the fifth and sixth earls of Derby, who lived at nearby Knowsley Hall, were patrons of Shakespeare and his fellow actors and owned some of his plays. They also discovered there had been a theatre in Prescot, creating a link between Shakespeare and the town.

>>> Also read: Projects: The Box, Plymouth

>>> Also read: St HildaŌĆÖs College revamp: serenity and unity down by the river

>>> Also read: Projects: Bloomsbury Theatre, London

How was the theatre design established without any plans? It transpired the site of the proposed theatre was where PrescotŌĆÖs cockfighting pit was once located. A serendipitous, second link was established in that the royal cockpit theatre in LondonŌĆÖs Whitehall was used by the earl of DerbyŌĆÖs players.

This cockpit was built in 1533 by Henry VIII and was occasionally used as a theatre. In 1629 Charles I commissioned architect Inigo Jones to design a permanent theatre on the site. This featured an end-on stage with a decorative frons scaenae, an architectural Roman backdrop at the back of the stage.

Shakespeare North Playhouse has been designed so it can be configured in three ways: as theatre in the round like a cockpit, an end-on stage and a thrust stage. ŌĆ£We set out originally to do the cockpit at court, the 1629 theatre, and as discussions developed, we developed this broader brief to embrace that 100 years of history,ŌĆØ explains Mike Yates, director at architect Austin-Smith:Lord, who has worked closely with Helm Architecture on the design.

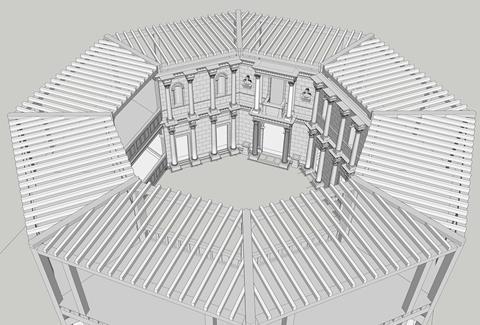

How did the team get from this concept to a green oak-framed theatre arranged as a double octagon capable of seating 470 people? A common thread running through the Globe, the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and the Shakespeare North Playhouse is Peter McCurdy, whose firm McCurdy & Co built all three auditoriums and, in the case of the Globe, the building frame, too.

He explains that there were records of the royal cockpit. ŌĆ£We know it was an octagonal building from maps and illustrations of London in the 16th century, and there is a painting from the middle part of the 17th century which shows it to be a fairly substantial, prominent building.ŌĆØ

Evidence of the changes made by Inigo Jones in 1629 came from historical drawings. ŌĆ£The evidence we have for the Inigo Jones conversion to a permanent theatre are drawings that were discovered in Worcester College Library in Oxford in the 1960s,ŌĆØ explains McCurdy.

ŌĆ£Someone pulled a book from one of the shelves and out fell the plans. They clearly show the polygonal form of the building, they give us the size of the building, and they show the detail for the frons scaenae.ŌĆØ

The drawings for the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse came from the same Oxford library and were used to design that building, although McCurdy says the Jacobean detailing came from several other sources.

The auditorium

McCurdy explains that the primary reference for the Shakespeare North Playhouse auditorium was the lantern on Ely Cathedral, as this was a very similar size. Dating from the 14th century, this features eight huge posts nearly 1m wide on each point of the octagon.

To give the right interpretation of a Tudor cockpit structure, the main posts had to be ŌĆ£pretty substantialŌĆØ, McCurdy says, although not 1m across. The Shakespeare North Playhouse posts are 450mm wide as they had to be shaped to take five to six facets.

The octagonal shape of the auditorium means the beams supporting the levels above join the posts at an angle, so more material needs to be removed on one side of the post. ŌĆ£We did have some pretty sizeable trees,ŌĆØ McCurdy says.

We had to find a crane that would fit into the space and work within the constraints of the structure that was already up

Peter McCurdy, McCurdy & Co

The theatre has been built by Kier on a former car park that slopes 3.5m from one side to the other. This necessitated a contiguous piled wall to retain the ground on the high side. With bedrock close to the surface, the building sits on a raft foundation. The frame is insitu concrete, and the theatre is located inside a 19m-wide square box with 24m high walls. ŌĆ£It wasnŌĆÖt easy to construct because at first-floor level there is a big concrete acoustic floor which is the base of the theatre with an exhibition space underneath,ŌĆØ explains Andy Brayne, KierŌĆÖs project manager on the job.

The theatre box walls, which are visible from the foyers in the wrap-around area, were cast using heavily textured wooden boards which give these a characterful finish. A concrete mix consisting of 60% GGBS was used for these walls, which presented Kier with some challenges as such a high percentage of cement replacement slows down the concrete set and curing time for each lift. This meant pouring the concrete more slowly to give it time for the initial set, so it didnŌĆÖt exert too much pressure on the shuttering. ŌĆ£It took a full day to pour the concrete as you could only do so much at once,ŌĆØ says Brayne.

He explains the wrap-around structure followed on from the theatre box. ŌĆ£The critical path for the project ran through the theatre,ŌĆØ he says. The theatre roof is constructed from four 3m-deep, 19m-long steel trusses ŌĆō this creates the space for the technical theatre equipment, including the flying winches.

Cladding

The building is clad in a soft-red brick which references the neighbouring sandstone Jacobean church. The bricks also pick up on the shinier red brick used for low-rise buildings in the town.

The south elevation, which is the direction people approach the theatre, features glass curtain walling by the entrance with the other half of this elevation constructed from brick-clad sawtooth bays arranged vertically and a flying balcony in front. The overall effect is of a building at ease with its surroundings yet clearly a modern intervention in this predominantly Victorian area. There is no hint of the historic auditorium inside, which should add to the drama experienced by theatre goers when they first step inside.

The historic, oak auditorium is a freestanding structure inside the concrete theatre box. ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° the box and constructing the roof before building the auditorium meant the construction of the latter would not impact on the overall programme and had the advantage the oak would be protected from the weather.

The oak frame was made in McCurdyŌĆÖs workshops. English oak was used for the 16 posts supporting the auditorium structure and European oak for secondary elements including the floor joists. The facets on the posts were cut using a band saw. ŌĆ£In HenryŌĆÖs day this would have been done by hand, and is something IŌĆÖd love to do but it isnŌĆÖt feasible on a project like this,ŌĆØ McCurdy says.

ŌĆ£The challenge began when we started erecting it on site,ŌĆØ he explains. The posts had to be brought in through the openings to the auditorium. Each post weighs about a tonne, with the outer posts erected just 200mm away from the concrete box walls. ŌĆ£We had to find a crane that would fit into the space and work within the constraints of the structure that was already up and allow us to put the frame together,ŌĆØ McCurdy says. He used spider cranes on the earlier theatres, but the heavy posts necessitated a much bigger spider crane than used before. The other challenge was that the constrained headroom ruled out the use of a chain and sling on the end of the crane to support the post whilst being lifted.

The solution came from GGR, the hire company used by McCurdy for the spider crane. They had developed a hydraulic grab for lifting steel beams. They modified this to fit on the spider crane so it could clamp onto the timber posts, lift and twist these upright for positioning ŌĆō a solution McCurdy describes as ŌĆ£brilliantŌĆØ.

The posts and beams are fixed with pegs that pull the mortice and tenons together, forming a solid joint. The balustrading at the front of the auditorium structure is based on Tudor panelling in a museum in Walthamstow. The auditorium is finished apart from the frons sceanae, which will be installed at the end of this year. It consists of three bays ŌĆō each facet is 4m wide and the whole is 6m high and designed to be demountable to enable the theatre to be used in the round. In contrast to the simplicity of the auditorium, the frons scaenae is richly decorated and includes 10 columns and 20 elaborate capitals which are being carved using a CNC machine, as doing this by hand would be prohibitively expensive. The green oak will shrink as it dries, so the thresholds between the auditorium and the foyers have been designed to be replaceable.

O Prescot, thou art changed

The Shakespeare North Playhouse never would have been realised without the efforts of Knowsley metropolitan borough council. Mike Harden, its chief executive, explains that Prescot was a traditional market town with thriving clock and watch making and cable manufacturing industries that have now gone with online shopping, chipping away at the retail centre to the extent that Knowsley is now the second-most deprived borough in England. Something had to be done.

ŌĆ£There were numerous academics who were talking about the fact there was this connection between Shakespeare, Knowsley, Prescot and the theatre. We realised that, unlike many places that build upon their history and generate an identity for their place, we werenŌĆÖt doing that for Prescot,ŌĆØ Harden says.

The council evaluated the likely benefits of capitalising on this history by building a new theatre, but Harden concedes it was a big gamble. ŌĆ£This is the biggest place-shaping initiative that Knowsley has done in its existence,ŌĆØ he says, adding that the council was not afraid of taking that step.

The council worked with the Shakespeare North Trust, which will run the new theatre. In 2007 it made a ┬Ż25m bid for lottery funding to realise the theatre but was turned down. Undeterred, Knowsley council decided to go it alone by investing ┬Ż12m.

The Liverpool Combined Authority, of which Knowsley is part, put in a further ┬Ż10.5m and the Treasury contributed ┬Ż5m, with another ┬Ż3.5m coming from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. In 2016 the council was in a position to give the project the green light.

Harden says that building the theatre has had dramatic benefits for Prescot in addition to creating jobs on the project. This includes 1,500 homes being built locally and numerous businesses opening to capitalise on the expected 140,000 visitors a year, who will boost the local economy by ┬Ż5.3m.

ŌĆ£Once we said we were going ahead with it, we saw private sector independent businesses open in Prescot; even before planning permission was granted, people were opening restaurants. The energy that is in Prescot now is huge.

ŌĆ£We are seeing the benefits of that ŌĆō jobs and businesses being created, housing growth ŌĆō housing developers have moved in and built houses, Prescot as a place is growing, and people are talking to us about how we are doing it.ŌĆØ

What are the lessons for the governmentŌĆÖs levelling up agenda? According to Harden, the Whitehall policy has not been much help to Knowsley. ŌĆ£We bid for support from the towns fund and didnŌĆÖt get anything. We bid for support from the future high streets fund and didnŌĆÖt get anything. We bid for support in the first round of the levelling up fund and we didnŌĆÖt get anything. So, the three significant initiatives in the last couple of years from this government aimed up at levelling up have not done anything for Knowsley.ŌĆØ

Harden reiterates his point that the areas need to get on with regeneration regardless of government support, ideally by devolving funding to those local areas. ŌĆ£Do we sit and complain about that and say we canŌĆÖt do anything, or do we get on with it and do what weŌĆÖve done with the Shakespeare North?ŌĆØ

He adds that the key ingredient is having a vision for a place that local people can buy into. ŌĆ£The starting point is vision, and itŌĆÖs got to be a vision that local people believe in. The people of Prescot talk about our playhouse, our theatre.

ŌĆ£When Kier put the crane in place ŌĆō which you can see from miles away ŌĆō the people of Prescot gave it a name. It was their crane; it was an amazing thing. So, you need a vision, but one of the greatest things weŌĆÖve been able to do is build on the enthusiasm of local people. They love their town.ŌĆØ

Tudor ├Ā la mode

Despite the care taken over the historic elements of the auditorium, it is not a slavish imitation of a Tudor cockpit. The concrete box forms the outer walls of the theatre, which have been left exposed and will be visible to the audience ŌĆō a simple solution that sits easily with the oak. There was no evidence of what the seating would have looked like, so the architects opted for benches upholstered with a light-grey wool covering. ŌĆ£Rather than trying to recreate a guess, weŌĆÖve just kept a very simple background with oak frame as the main piece,ŌĆØ Yates explains.

The theatre also comes with a full complement of modern theatre lighting, sound systems and flying equipment. The technical equipment is mostly on the level above the second auditorium level and will be partially hidden behind a calico screen painted with stars that will be suspended from above. An authentic touch is candelabra which will hold beeswax candles lit for performances.

The first public performance is a free opening celebration by Alan Lane which will take place in the public piazza outside the theatre on 15 July. Shakespeare North Playhouse also features an outside theatre space with stepped granite seating that was funded by the Ken Dodd foundation. The first performance in the cockpit theatre is an evening with writer Jimmy McCovern, who will be interviewed by another local thespian, Jonny Vegas. Shakespeare lovers will have to wait until late September to get the full Tudor cockpit experience when A Midsummer NightŌĆÖs Dream will be performed, and the theatre will become fully alive. According to Yates, this will be the first time in 400 years that audience and actors will have had the opportunity to experience Shakespeare in such a setting. Given the care lavished on the research, design and construction of this building, it should be well worth the wait.

Project team

Client Knowsley metropolitan borough council

Concept architect Helm Architecture

Executive architect Austin-Smith:Lord

Theatre consultant Arup

Structural engineer Mott MacDonald

Service and accoustics engineer Aecom

QS Aecom

Main contractor Kier

Auditorium specialist McCurdy & Co

Theatre operator Shakespeare North Trust

M&E specialist Dodd Group

No comments yet