So, what about the fruits of services engineers’ labours? We asked a panel of sector leaders and academics to name 30 projects that have reshaped the built environment over the three decades since BSj’s inception in 1978

Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh

The briefing for this project put environmental concerns at the heart of the design. The stated aims were a BREEAM excellent rating and the ‚Äúgood practice‚ÄĚ benchmark under Econ 19. RMJM used natural ventilation in most areas, even where the depth of plan would normally preclude it, plus low-velocity displacement ventilation and

comfort cooling, partly through the use of boreholes inherited from the previous site owner, brewer Scottish & Newcastle. Solar panels and a combined heat and power boiler also reduce energy use.

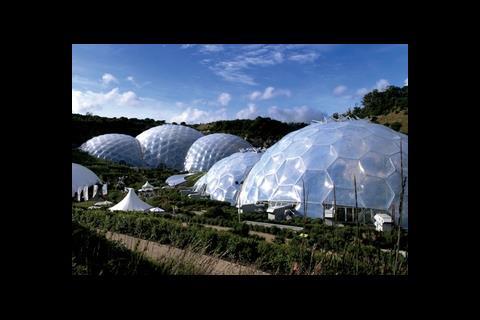

Eden Project, Cornwall

The Eden Project, by Nicholas Grimshaw with services by Arup, makes the list as much for its ethos as its design. One expert describes it as a ‚Äúsimply joyful place‚ÄĚ, but says it is challenging from an engineering perspective because of the difficulty in ventilating it without upsetting the plants. Plans are in the pipeline for a new building, called The Edge, which will look to examine and tackle the issues of climate change.

British Library, London

The library holds 13 million books and is mammoth both in size and achievement. It was the largest public building constructed in the UK in the 20th century, with more than 112,000m2 spread over 14 floors, five of them underground.

Reichstag, Berlin

Yet another Foster and Partners scheme, the Reichstag glazed dome serves to bring daylight deep into the building while the inverted cone within the dome helps rid it of hot air. Other features include a bio-fuel powered co-generation system to produce electricity, and the use of the ground to store energy for heating and cooling.

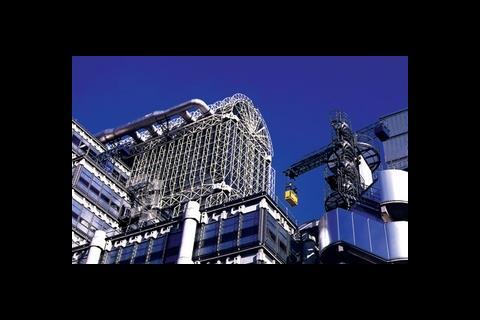

Lloyd‚Äôs ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, London

Richard Rogers‚Äô Lloyd‚Äôs ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, completed in 1986, still wins praise from our panel for its use of external services which, as at the Pompidou Centre, allowed for large areas of unobstructed interior space. Arup‚Äôs design has six satellite towers housing external services which form a flexible framework for the ventilation plant, lifts, services risers and lavatories.

Commerzbank Tower, Frankfurt

The 53-storey tower, completed in 1997, has been called the first green high-rise. The aim was to reduce dependency on fossil fuels through an innovative facade system and a series of sky gardens with a central atrium for natural ventilation. A chilled ceiling and perimeter radiators provide back-up. The Foster tower is not without critics. ‚ÄúIt is nowhere near as green as some believe it to be,‚ÄĚ one panellist said.

CH2, Melbourne

Council House 2 was the first scheme to achieve the highest environmental building rating in Australia ‚Äď six green stars. With services by Lincolne Scott, it is estimated to produce just 13% of the emissions of a typical building and includes chilled ceilings fed by cooling plant using phase change materials. It draws water for toilet flushing by mining the public sewer. One of the key conditions of engagement was for the consultants to share all newly generated intellectual property.

L’Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris

The Arab World Institute, designed by Jean Nouvel, is a mixed-use cultural centre near Notre Dame. Its impressive south-facing facade is an example of how innovative engineering can enhance an architectural concept. The facade is constructed of more than 200 aluminium panels that have a variable diaphragm, like a camera iris, to control the intensity of light filtering into the building’s interior.

30 St Mary Axe, London

Arguably London‚Äôs first green tower, the 180m high ‚ÄúGherkin‚ÄĚ has dominated the City skyline for four years. The 2004 Stirling Prize winner was designed by Foster + Partners with services by Hilson Moran. Cigar-shaped, it has spiralling atriums with opening windows to allow the floors to be naturally ventilated when wind speed is below 10mph and external temperature between 20¬ļC and 26¬ļC.

Gateway 2, Basingstoke

When Wiggins Teape occupied Gateway 2 in 1983, it was one of the first examples of a business moving from a fully air-conditioned office into a naturally ventilated building. Arup used computer simulation to model the stack effect of heat rising in the building’s central atrium, drawing fresh air in from the perimeter through the offices. The need for summer cooling is avoided through Arup’s use of fixed summer shading and the thermal mass in the exposed concrete of the office ceilings.

The Ark, Hammersmith

Architect Ralph Erskine created a landmark for motorists driving in and out of London on the A4. His office building, which derives its name from the hull-like profile, was completed in 1992 and underwent an extensive refurbishment 15 years later at a cost of about £20m. Almost half of the budget was allocated to building services, designed by RYB Konsult. The main change was the replacement of the air supply and return system, which had failed to meet the requirement of operating separately on each floor to suit individual tenants. Other features of the refurbishment included the creation of a double-height atrium on the ground floor. Each floor can now be subdivided into two spaces and the open balustrade has been replaced with partially glazed partitions.

Innovate Green ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, Leeds

This scheme is included not only because it attained the highest ever BREEAM score of 87.5%, but because it is a great example of what can be achieved, both environmentally and commercially, when engineering is allowed to lead the design process. Engineer King Shaw Associates was involved in the selection of construction components based on their contribution to the overall building performance. This gives a more holistic, sustainable solution than is provided by simply adding green bling. Completed in 2007, the building’s carbon emissions are predicted to be at least 80% less than for a typical office building.

Apollo theatre, Victoria

The refurbishment of the Apollo Victoria in London makes the list for exploiting the potential of LEDs on a scale not previously seen in the UK. The auditorium, dating from 1929, previously had 3500 GLS lamps. The new scheme, designed by Hoare Lea, replaced them with 84000 LEDs to recreate the original design, which sought to give the illusion of an underwater palace. The LEDs save energy to boot.

30 The Bond, Sydney

This was the first office building to achieve a five-star rating from Australia‚Äôs Green ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý Council, equivalent to a BREEAM excellent rating in the UK. The design includes concealed passive chilled beams ‚Äď the first large-scale installation of this technology in Australia ‚Äď and a ‚Äúsingle- pass‚ÄĚ fresh air system. The building incorporates an exposed rock wall, hewn by convicts in the 1800s, which is the longest and oldest sandstone cutting in Sydney. The piece of history is given a good display but also assists in the radiant cooling of the atrium. Moist airflows coming off the wall are engineered to minimise the risk of humidity and condensation. Environmental design was by Bovis Lend Lease, mechanical engineering was by Lincolne Scott and electrical design by Connell Mott MacDonald. Despite being met with great scepticism by the building services industry during the design and construction phases, it has operated for more than four years without problems, staying within +/-6% of the original bold energy estimate of 50% below the Sydney average.

Le Centre Pompidou, Paris

The arts complex, opened in 1977, warrants inclusion for literally putting the work of the building services engineer on view. The architects, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, came up with a design that not only showcased Arup’s services scheme but allowed the creation of vast uninterrupted interior spaces.

Emirates Stadium, London

Arsenal’s football stadium was a popular nominee, while its counterpart along the North Circular Road in Wembley wasn’t even close to making the list. Perhaps it was something to do with the well-publicised problems during construction of England’s national stadium and the fact that the Emirates came in on time and within budget. Where the Emirates scores over Wembley is the construction of the services in modules, so that the stadium can operate in zones when it hosts smaller events.

Masdar, Abu Dhabi (design stage)

The construction of Masdar is a sign of the Middle East’s increasing commitment to the green construction agenda. Commissioned by the United Arab Emirates and designed by architect Fosters + Partners, Masdar will be built on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi. The walled city, with its buildings set close together to provide shade, is intended to house 50,000 people and 1500 businesses and will rely on renewable energy sources, mainly solar power. The designers’ aim is to halve the average per capita water consumption and reuse all waste water. Drinking water will be provided by desalination plants, powered by solar energy.

Terminal 5, Heathrow

The £4.2 billion, multi-consultant project impressed our panel particularly because more than 60% of the £600m of services was assembled offsite by Amec and others. The vast terminal, now functioning well after a notoriously troubled opening, houses one of the largest M&E installations undertaken in the UK. Initiatives such as integrated teamworking, smart logistics and a single virtual project computer model all contributed to the scheme opening on time.

Elizabeth Fry ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, Norwich

This scheme for the University of East Anglia could be the best building ever ‚Äď according to BSj‚Äôs PROBE evaluation.

Designed by architect John Miller + Partners and services engineer Fulcrum, it is tightly sealed, triple-glazed and well insulated. It was one of the first UK developments to use the Swedish TermoDeck ventilated hollowcore slab system for the structural ceilings. The building, which was occupied in 1995, was described in BSj as a ‚Äúrole model for future building development and management‚ÄĚ.

Clore Gallery extension, Tate Britain

Architect James Stirling’s design was significant in that it helped to introduce daylight as an active element in a modern gallery. The ceiling has deep fixed baffles that cut out sunlight but scoop in light from the north so that variations in daylight diversity occur in the space. The extension, on London’s Millbank, opened in 1987.

The Mint, Sydney

This building is the home of Australia’s Historic Houses Trust. The refurbishment project is an example of the integration of services systems (by Steensen Varming) to provide a modern, functional headquarters while minimising the impact on the heritage and archaeological fabric of a site.

Broadgate, London

The Broadgate development, completed in 1988, is included for being among the first to bring US construction techniques to the UK.

A vast City of London estate masterplanned by Arup Associates, Broadgate consists of 15 buildings (of which Arup designed the first four). It provides a total of 4.8 million ft2 of flexible office space, which can be reconfigured to install the latest technology or change floor layouts.

One Churchill Place (Canary Wharf), London

As the first high-rise to be built in the UK following the 11 September terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York, security was a significant focus at One Churchill Place, the new headquarters of Barclays Bank. It has been hailed as one of the most robust buildings in the world. It features air-conditioning intakes placed on the roof to hinder bio-terrorists, an increased number of fire escape staircases and wider than standard stairs, encased in 400mm thick concrete walls. Despite its robustness, the building still managed to achieve a BREEAM excellent rating.

McClaren Technology Centre, Woking

Attention to detail is the reason for the inclusion of the Norman Foster-designed McLaren Technology Centre. Despite being the home of Britain’s most successful Formula 1 motor racing team, this 57,000m2 building is also environmentally friendly, with natural light used wherever possible and energy recycled throughout the site. The main body of the building is split into 18m-wide fingers to maximise daylight in the offices, while water from the giant lake fronting the building is used to help cool it.

BRE Environmental ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, Watford

A prime example of what can be achieved by the successful integration of architecture, services and structure to reduce energy use. The building, completed in 1996, uses 30% less energy than a conventional best practice office by avoiding the need for air-conditioning and making use of the sun to power the distinctive solar chimneys that help ventilate the offices and seminar rooms. The scheme also incorporated much of the demolition waste from the building that previously occupied its site. Services were by Max Fordham.

Beaufort Court, King’s Langley

An old chicken shed might not seem the most likely starting point for cutting edge offices, but for wind farm developer Renewable Energy Systems it made perfect sense ‚Äď the firm wanted all the energy for its offices to be produced on site. The solution, developed by consultant Max Fordham in 2003, involved the installation of a wind turbine (unsurprisingly), a combined thermal and photovoltaic solar panel system, ground water cooling and a large thermal heat store. The building also features a biomass boiler supplied with fuel grown on the surrounding land. Some elements worked better than others, but overall the project has been a success.

Sainsbury Millennium Store, Greenwich

The low-energy food store on the Greenwich peninsula is the only retail building to make it on to the list. It is nominated for being a pioneering low energy design in a traditionally energy intensive sector. In addition to the wind turbines that generate power to illuminate advertising hoardings, other low energy features include earth berm walls, a naturally lit sales floor and wall panels in the toilets made from recycled plastic bottles. M&E was by the then-named Oscar Faber.

Burj, Dubai (under construction)

The Burj is included simply for being the tallest building in the world ‚Äď although quite how tall it will end up is a closely guarded secret. This megastructure is effectively a small town with retail, commercial, hotel and residential. Its peak cooling load is estimated at 53MW by the MEP team at architect SOM. Greener features include using condensed water from the air-conditioning system‚Äôs cooling coils ‚Äď estimated to be over 50 million litres a year ‚Äď to irrigate the planting. Other key statistics include a 45MVA electrical load and a 18m/s (40mph) lift to whisk people up to the viewing gallery. The lifts form part of the fire evacuation system.

Dongtan eco-city, China

Dongtan is China’s first eco-city, designed by Arup. The aim is to create a development that is as close to carbon neutral as possible and sustainable environmentally, socially, economically and culturally. Dongtan will produce its own energy from wind, solar, bio-fuel and recycled city waste. Clean technologies such as hydrogen fuel cells will power public transport and there will be a network of cycle and footpaths.

Hearst ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý, New York

As energy efficiency for tall buildings becomes a hot topic, the Foster + Partners-designed 46-storey Hearst ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý has raised the standard in New York by being the first tower in the city to achieve a Gold Rating under the US Green ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý Council‚Äôs LEED scheme. The services design, by engineer Flack + Kurtz (part of the WSP Group), uses 26% less energy than a conventional tower built to standard building codes. The building also collects rainwater from the roof and uses this to help cool and humidify the huge ground-floor atrium.

Source

ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ý Sustainable Design

Postscript

Agree or disagree? This list was compiled with the help of the votes of leaders from within the building services industry. Like anything subjective, the results are open to debate. Do you agree with their choices? Are they too UK-focused? Tell us what you think. Email bsjeditorial@cmpi.biz

No comments yet