London wakes up to the threat of aerial bombing as total war grips the country, and the construction industry

Great Britain was on the brink in January 1918. The conflict in Europe was halfway through its fourth year, and by this point country and the construction industry was gripped by the conditions of total war imposed by the government. The press was silenced, conscription had been imposed, and industries, including construction, were state-controlled. “There is little to record,” The Builder admitted, as almost all construction work was being carried out by government departments “under a veil of partial secrecy”.

The magazine started the new year with a special issue on the impact of the war and the prospects for the future. It includes a personal account of an air raid in London which had smashed the writer’s window and driven “spear-like fragments” into the opposite wall. The raids had started the previous year and were increasing in frequency. For the first time, the capital was waking up to the threat of aerial bombing.

Although the US had now entered the conflict on the side of the allies, the country was yet to mobilise and there is little sense at the beginning of the year that 1918 would mark the end of the war. It would get worse before it got better - in the spring Germany would launch a massive offensive, taking huge swathes of Allied-held land before its armies stalled in the summer and fell back for the last time.

Extract from leading editorial, 4 January 1918

PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE

A year ago most of us anticipated that another twelve months would witness the end of the European War; eight months ago we all thought the German line of steel in the West might have been shattered; but our hopes have proved illusory, mainly owing to the consequences of the Russian Revolution. But if our desires have been brought to nothing by fate, we have had the immeasurable satisfaction of seeing America leave the ranks of neutrals and devote herself whole-heartedly to the conflict with the common enemy. The fact that she has done so may in the end prove to have brought about victory more completely than would have been the case had not the aims of Russia been changed. But for a time we are suffering from the paralysis of a former ally, while it is too early to feel the immense impetus which will be given when America has been converted into an armed nation. We live in a time when partial secrecy veils activity, and it will not be till peace comes that we shall know what has been done during war time. We hear, as our forefathers might have heard, of immense undertakings of all kinds in different parts of the land by the vague hearsay of those living near centres of activity, for under the conditions of the time the Press is silenced. The controller’s authority spreads like a lichen over one industry after another, stopping some and carrying out others for new purposes under a system of control. Of effective criticism there is none, for few know all the facts, and the few who do may say nothing.

At the end of the war only will it be possible to form a general view of what has been done in our midst, and how far the authorities have wisely used the powers given to them in the present emergency. Both the profession of architecture and the industry of building have lost many of the most promising of their younger members, whose untimely end we all deplore; but their friends may have some consolation in feeling that they have given their lives that future generations, as well as our own, may be able to live under happier conditions than those of the past fifty years, and that without the immense sacrifices made by all the allied countries Europe would have been doomed to succumb under a soulless and brutal tyranny such as the world had never known.

As almost the whole of the building of the country is being carried on by Government Departments under a veil of partial secrecy, there is little to record. One after another the great public buildings in course of erection have been stopped, no private work except that for controlled firms and other than the smallest works can be carried out, and it is now proposed to carry the restrictions still further. If we believed that these regulations were calculated to further our national ends, we should be among their supporters, but it is at least questionable whether a useful purpose is served by the further extension of a system of restriction.

Extract from news item, 4 January 1918

A GOVERNMENT HOUSING SCHEME.

ROE GREEN VILLAGE SCHEME, KINGSBURY

We have obtained the permission of the controlled firm for whom the Office of Works are now carrying out a housing scheme at Hendon, to place before our readers plans and details showing what is projected. The general layout and detailed planning are admirable, and may be specially useful at this juncture in setting a standard which is good without being extravagant, and is free from any superfluities which are not required, and which too often characterise the work of those inexperienced in practical problems of design.

Extract from feature, 4 January 1918

AIR RAIDS AND OUR BUILDINGS

London must by now have experienced something approaching a score of air raids, which have brought disaster to a great variety of buildings, and with such disaster a good deal of experience. Attacks have been made by means of high explosive, incendiary and other bombs, of various sizes, from different types of aircraft, but it seems probable that the chief provisions of the future will have to be against heavier-than-air machines dropping high explosives from considerable altitudes.

It has already been made evident that a large measure of protection can be obtained by adopting certain elementary precautions, and no doubt experts have collected a good deal of information as to the comparative resisting power of various buildings under different conditions. The writer is not aware of any lay summary of such observations which has been placed at the disposal of the public, and assuming that no such brochure exists, it seems desirable to consider whether such information could be usefully published. By this it is not suggested that the ordinary householder should be encouraged to endeavour to erect bombproof shelters on his premises, which might readily result in disaster greater than might occur if he refrained from such attempts, but rather to enable him to decide what he can and cannot do in the matter of protective measures.

Approaching the subject entirely in a spirit of enquiry, without any claim to expert knowledge, the forms of protection to be considered seem to fall under the following heads: 1. From small flying fragments; 2. From fire; 3, From poisonous gases; 4, From serious collapse of buildings; 5, From direct hits by bombs and unexploded shells. Protection from flying fragments can be obtained by taking ordinary precautions to keep indoors, away from glass and the path which glass fragments might take, and to shelter behind something in the nature of a strong and solid barrier. In this connection it is not always realised that many roofs possess no boarding under the slates, which means, that unless shell fragments happen to strike a rafter or ceiling joist, the chance of which will usually be about 1 to 6, there is nothing above the occupants of the top floor beyond two thicknesses of roofing slates and three-quarters of an inch of lath and plaster, which is wholly insufficient to stop a dropping shell fragment even from an inconsiderable height.

As to glass, the writer can quote a personal experience in which the concussion of a large explosive bomb, falling on a tar-paved surface about 50 ft. from his windows, measured at an angle of about 60 degrees with the face of the building, blew in 1-inch plate glass windows about 15 in. wide with sufficient force to drive spear-like fragments into the hard plaster of the opposite wall 15 ft. distant (where they are still preserved), the windows being about 45 ft. above the ground. In this case the building forms part of a court, the opposite wall of which is about 120 ft. distant. The effects of air concussion, of course, depend very largely on the proximity of surrounding buildings, and would be greater in a narrow street.

Little need be said about protection from incendiary bombs. The ready availability of vessels of water has been publicly enjoined, while for the rest ordinary means of fire protection can be utilised. In fighting fire time is everything, and a syphon of soda water immediately accessible may often be worth more than apparatus which, unless frequently inspected, may take a minute or two to bring into action. In selecting a place in which to congregate during a raid, an alternative way of escape in case of fire should always be a matter for consideration.

We have fortunately not had many experiences of poisonous gases, though at one time such visitations were confidently anticipated. Such gases would probably result from the almost instantaneous evaporation of liquid chlorine or the liquids bromine, phosphorus, trichloride or oxychloride, though, of course, many other compounds are available. A supply of pads soaked in a solution of washing soda, which can be placed over the mouth and nostrils, forms the simplest safeguard; but, as in the case of fire, an alternative way of escape should be provided as an additional safeguard.

Feature, 4 January 1918

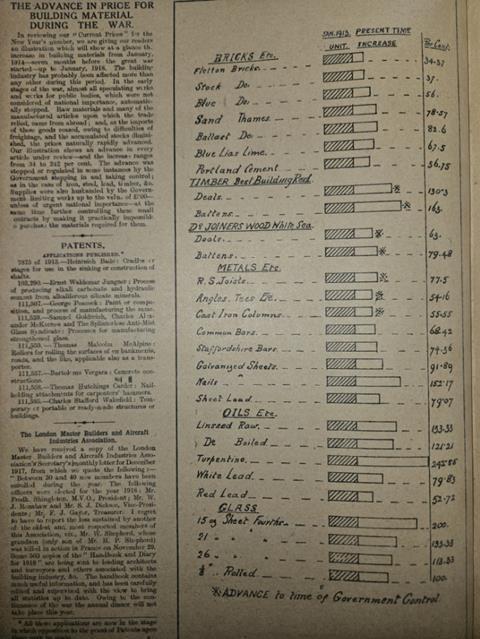

THE ADVANCE IN PRICE FOR BUILDING MATERIAL DURING THE WAR.

In reviewing our “Current Prices” for the New Year’s number, we are giving our readers an illustration which will show at a glance the increase in building materials from January, 1914 - seven months before the great war started - up to January, 1918. The building industry has probably been affected more than any other during this period. In the early stages of the war, almost all speculating works and works for public bodies, which were not considered of national importance, automatically stopped. Raw materials and many of the manufactured articles upon which the trade relied came from abroad; and, as the imports of these goods ceased, owing to difficulties of freightage, and the accumulated stocks diminished, the prices naturally rapidly advanced. Our illustration shows an advance in every article under review - and the increase ranges from 34 to 242 per cent. The advance was stopped or regulated in some instances by the Government stepping in and taking control; as in the case of iron, steel, lead, timber, etc. Supplies were also husbanded by the Government limiting works up to the value of £500 - unless of urgent national importance - at the same time further controlling these small contracts by making it practically impossible to purchase the materials required for them.

More from the archives:

>> Nelson’s Column runs out of money, 1843-44

>> The clearance of London’s worst slum, 1843-46

>> The construction of the Palace of Westminster, 1847

>> Benjamin Disraeli’s proposal to hang architects, 1847

>> The Crystal Palace’s leaking roof, 1851

>> Cleaning up the Great Stink, 1858

>> Setbacks on the world’s first underground railway, 1860

>> The opening of Clifton Suspension Bridge, 1864

>> Replacing Old Smithfield Market, 1864-68

>> Alternative designs for Manchester Town Hall, 1868

>> The construction of the Forth Bridge, 1873-90

>> The demolition of Northumberland House, 1874

>> Dodging falling bricks at the Natural History Museum construction site, 1876

>> An alternative proposal for Tower Bridge, 1878

>> The Tay Bridge disaster, 1879

>> �ڶ����� in Bombay, 1879 - 1892

>> Cologne Cathedral’s topping out ceremony, 1880

>> Britain’s dim view of the Eiffel Tower, 1886-89

>> First proposals for the Glasgow Subway, 1887

No comments yet