For his next trick, Norman Foster is going to turn a patch of desert in Abu Dhabi into the worldŌĆÖs first zero-carbon, zero-waste city. Martin Spring finds out how

ŌĆ£The Alhambra on steroids,ŌĆØ is how Gerard Evenden, senior partner at Foster + Partners, describes the Masdar initiative. It is a catchy line and a bold comparison, but then this is a project littered with big claims. The development in Abu Dhabi, which will be home to 47,500 people with an additional working population of 60,500, has been billed as the worldŌĆÖs first zero-carbon, zero-waste city. Its developer, the government-owned Future Energy Company, sees it as ŌĆ£a centre for the development of new ideas for energy productionŌĆØ, and a sustainable urban blueprint for the future. These are no mean feats in a ferocious desert climate, where average summertime temperatures top 40┬░C.

In the era of global warming, zero carbon has become the holy grail for many ambitious new developments across the world, and zero waste follows close behind as an aspiration. The big question is what are the Masdar initiative's chances of achieving such elusive targets.

A sceptical reception comes from environmental engineer Chris Twinn of Arup, who has been involved in the Dongtan zero-carbon venture in China. He argues that, in sweltering desert conditions, air-conditioning levels cannot reasonably be reduced, while renewable energy sources such as photovoltaics operate with lower efficiency. Added to that he points out that occupantsŌĆÖ lifestyle choices, such as their increasing desire for comfort and electronic gadgetry, could play havoc with the levels of energy use that the city is designed to meet, thereby making the zero-carbon target ŌĆ£virtually impossibleŌĆØ to achieve.

Just three months into this hugely ambitious project, Foster and accountant Ernst & Young are still grappling with how to balance out the energy and material inputs and outputs to produce zero carbon and zero waste. With Foster as the lead consultant, the scheme is certain to set out its stall as being at the leading edge of sustainable design. But that does not mean that itŌĆÖs all photovoltaics and other sci-fi gizmo.

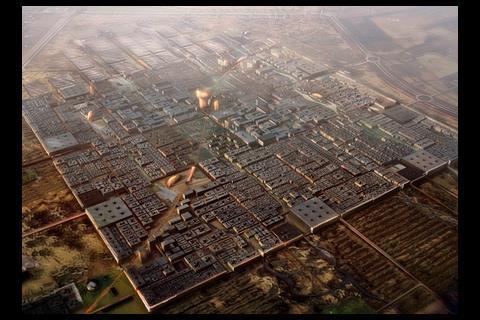

In fact, the city is largely planned on traditional Arabic lines, hence EvendenŌĆÖs reference to the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. An array of Arabic forms have been mobilised to conserve energy by curbing soaring temperatures. These start with a high-density town plan of rectilinear city blocks ŌĆō not unlike that of Abu Dhabi itself ŌĆō in which some 6 million m2 of living space will be condensed into a walled city of just 2.8km2. This amounts to a pressure-cooker population density, combining residents and working people, of 364 people to the hectare.

The compact urban form has many advantages: it cuts travel distances, which is useful since personal cars are banned; the narrow streets, many of which are just 3m wide, allow pedestrians to walk in the shade; the streets and public outdoor spaces are all covered by awnings, as in traditional Arab bazaars; and the 12m high city walls are intended to prevent urban sprawl.

On top of that, narrow canals filled with the cityŌĆÖs grey water will run alongside the streets to help cool the air above them. The canals will be orientated to run north to the shoreline of the Persian Gulf, to channel cooling sea breezes into the heart of the city.

Finally, despite the high density, the buildings will rise no higher than five storeys, to avoid the need for energy-guzzling lifts.

On the high-tech side, the main components will be PV cells that will harness sunlight. As well as being draped over rooftops and south-facing walls, panels of PV cells will form the awnings over external spaces.

ŌĆ£This is not some twee model village,ŌĆØ says Evendon. ŌĆ£It is important that the science of what is supporting the city is fully visible.ŌĆØ

More radical than that, the enabling phase for the whole city will take the form of a vast PV power plant measuring 750 ├Ś 750m. This will generate the energy to build the city, and as that nears completion, the PV panels will be transferred to permanent structures within the city. Even so, Evenden is wary of regarding photovoltaics as a panacea. If their efficiency is not to plummet, PV panels must be continually ventilated and cleaned of wind-blown dust, neither of which is an easy matter in desert conditions. So the team is also looking at more conventional water-based solar collectors.

A more futuristic note will be added by a system of driverless electric taxis, running on raised tracks. In addition, an electric light rail system will link the town to neighbouring settlements.

In the open land outside the city walls, wind farms will harness sea breezes, and plantations of biofuel crops will be cultivated. Here, recycling plants will salvage spent materials from the working city, leaving the residue to be incinerated to produce more energy.

When it comes to fresh water in the desert-region city, there will no escaping the energy-intensive process of desalinating sea water. But here again, as Evenden explains, the aim is to cut the supply of desalinated water by 80%, first by cutting occupantsŌĆÖ water consumption by half, then by recycling half of that as grey water. After that, all but the 10% of water that is unfit for recycling will be fed into plantations and gardens.

The Future Energy Company, envisages that Masdar will serve as advanced technological university and science park, peopled by top scientists, students and businessmen from all over the world. It already has strong links with universities across the world, including MIT in the US and Imperial College in London. It is also in the forefront of PV technology, working in association with the German company Sulfurcell.

Foster has assembled an international team of technical consultants that includes Transolar of Stuttgart for the environmental programme, WSP Energy for water and telecoms, ETA of Italy for photovoltaics and Systematica of Italy for the driverless cars. Cyril Sweett is the construction cost consultant, and Ernst & Young is looking at the financial viability of the whole initiative.

The plan is that the first phase, including a university campus, will be completed by 2009.

Meanwhile, in China ...

The Dongtan Eco-City, planned for an island in the mouth of the Yangtze River near Shanghai, is China's answer to Abu Dhabi's Masdar Initiative. Like Masdar, Dongtan is conceived as a new-build city that will be sustainable, 100% powered by renewable energy and carbon-neutral. But with a total population projected at 500,000 by 2050, it will be five times the size of Masdar. The developer is the Shanghai Industrial Investment Corporation, and its urban design, energy strategy and economic plan are all the work of Arup.

Also like Masdar, Dongtan is planned as a dense, walkable, relatively low-rise city, in this case at 167 persons per hectare with most buildings rising six storeys. Instead of a walled city on a gridiron plan, it has a linear plan along the main public transit corridor.

DongtanŌĆÖs main source of renewable energy will be biomass, in particular ChinaŌĆÖs most ubiquitous waste product ŌĆō rice husks. ArupŌĆÖs clever trick here is not just to burn rice husks as fuel but to harness them for combined heat and power (CHP). With the CHP plant located near the city centre, along with efficient boilers and good insulation, Arup reckons it could reach 80% fuel efficiency, four times that of wood-chip-burning boilers.

But Dongtan will not rely purely on ArupŌĆÖs low-energy systems. A key ingredient will be severe curbs on how occupants operate them. All occupants will be assigned energy limits, and their buildings fitted with simple meters to check usage. If they overshoot their energy limits, they will be hit by penalties of 300% price rises.

Arup is awaiting the go-ahead for construction to start later this year. The first phase for 10,000 people could then be completed in time for Shanghai Expo 2010.

Postscript

ArupŌĆÖs Chris Twinn will be speaking at ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ°ŌĆÖs conference, The Cost of Going Zero Carbon, which will be held in London on 13 June. For more details, email catherine@moorestyle.co.uk

No comments yet