Dixon JonesŌĆÖ canalside Kings Place in London combines public concert halls and art galleries with private office space. It is an extraordinary hybrid of a building, says Martin Spring

The ultimate in mixed-use development is taking shape just a couple of blocks north of LondonŌĆÖs new international transport hub of KingŌĆÖs Cross St Pancras. Here at Kings Place, public high culture and amenities ŌĆō two concert halls, a string of art galleries and a clutch of restaurants and bars ŌĆō have been combined with private spec offices, including those of The Guardian and Observer newspapers. But these two normally conflicting uses do not stand bashfully side by side separated by a tasteful plaza. Uniquely in the UK, they are wrapped up together into a single four-square building with, from the outside at least, next to no visual distinction between them.

This extraordinary hybrid of a building is the vision of one man, developer Peter Millican. His stated aim for the building was ŌĆ£to create an architecturally inspiring mixed-use development which, without recourse to public [or Lottery] capital funding, would deliver a major new arts centre and offer something to the local communityŌĆØ.

The architectural inspiration comes from Dixon Jones, which hit the high notes in cultural architecture with the refurbishment of the Royal Opera House in 1999 and the National Gallery in 2005. In Dixon JonesŌĆÖ design, the buildingŌĆÖs dual public and private uses interact physically. The offices encircle and look down on a spacious public concourse that doubles as an art gallery, with restaurants, bars and cafes opening off it, and wide escalators leading down to the concert halls and more galleries tucked below.

The site is also extraordinary, as it is bounded on two sides by the RegentŌĆÖs Canal and Battlebridge Canal Basin ŌĆō the latter with its floating village of houseboats. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs water, peace and tranquillity here ŌĆō a huge difference from the hubbub of central London a few blocks away,ŌĆØ says Dixon Jones partner Sir Jeremy Dixon.

In responding to this splendid, tranquil site and to the high cultural uses to which it will be put, Dixon Jones has created a grand, stately, yet quite contemporary piece of civic architecture. The seven-storey building with floor-to-ceiling windows is faced in creamy-white Jura limestone that has been immaculately cut to reveal golden flecks running through it. Where the two stretches of water meet, the block gracefully curls round the corner with a cylindrical stone knuckle that rises up one floor higher. And the waterfront will be colonised by the restaurants, cafes and outdoor sculpture.

The third side of the building faces the busy approach road to KingŌĆÖs Cross St Pancras, and beyond that, the extensive railway lands where Argent is about to start its ┬Ż2bn regeneration extravaganza. As this is quite plainly an urban scene, the west facade ditches the stonework and abruptly switches into a sheer, blank window wall. But to avoid a dismal canyon effect, a lively ripple of shallow vertical waves has been added.

Inside the building, the two concert halls and main gallery have been relegated to two levels of basement. ŌĆ£The height of the building was absolutely controlled by Islington planners, so as not to block sightlines from the housing nearby,ŌĆØ explains Dixon. ŌĆ£The building was bigger than they expected, so we had to push a lot of it underground.ŌĆØ Fortunately, the auditoriums and gallery do not demand natural daylight and views, whereas the office workspaces do.

By far the most marvellous, and the most technically exacting, internal space is the pocket-sized auditorium with 420 seats. Millican has donated the hall and other facilities at peppercorn rent to two famous orchestras, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and the London Sinfonietta.

But the two orchestras, one early classical and the other tending towards electronic sounds, require quite different acoustics. Added to that, the auditorium sits close to the Piccadilly underground line, so a box within a box was necessary to block vibrations and noise. ŌĆ£Our starting point was to adopt the classic shoe box, or double cube, format, which gives the best acoustics,ŌĆØ says Dixon. ŌĆ£And then we added curtains to change the reverberation time.ŌĆØ

The resulting auditorium gives eloquent architectural expression simultaneously to the cubic shoe-box shape, the box-within-a-box structure and the dual-use flexibility. It is a rectangular hall surrounded on three sides by a repetitive, elegantly proportioned colonnade.

The free-standing columns continue the rectilinear geometry by being square sectioned, smooth and free of capitals and other mouldings. But there is nothing cold or severe about this insistently four-square interior, as it is entirely faced in flawless natural oak. The whole assemblage can be read as a truly modern descendant of the ancient Greek temple, although without a trace of pastiche.

In practical terms, the columns provide structural support to the timber inner ceiling of the box within a box. And to adjust the acoustics, a full-height grey curtain can be drawn all round the sides and back of the auditorium. It runs behind the colonnade, where it leaves the architectural integrity of the oak-lined hall intact.

When it opens in October, Kings Place will introduce world-class music and art to north London with a splendid new building to house it. Millican has achieved all this by subsidising the music and art with the revenue from the buildingŌĆÖs 26,000m2 of commercial office space.

In a capital city where office employment, cultural events and dining out are the main activities, it is a perfect self-sustaining ŌĆō and highly philanthropic ŌĆō combination.

ThereŌĆÖs water, peace and tranquillity here ŌĆō a huge difference from the hubbub of central London a few blocks away.

Sir Jeremy Dixon, Dixon Jones

A construction diary

Last month, Sir Robert McAlpine handed over Kings Place on time and within budget for six monthsŌĆÖ fitting out. Since the building is entirely funded on the back of its commercial office use, its procurement conforms to standard commercial practice. As a result, it was let to McAlpine on a ┬Ż97m design-and-build contract with a guaranteed maximum price.

Since guaranteed maximum price contracts are suited to relatively standardised office buildings rather than one-off signature arts projects, Sir Jeremy Dixon was rather apprehensive. But he says: ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm more than happy with what McAlpine has done. WeŌĆÖve not lost anything with the fixed-price contract: weŌĆÖve gained things.ŌĆØ The fact that McAlpine took on the original design team to carry out the more detailed side of things had helped smooth relations with the architect.

The following progress photographs of the 35-month contract reveal the sequence of construction challenges, including difficult council planners and traffic controllers, which his team had to deal with.

May 2006

As Islington council planners insisted that the building should rise no higher than seven storeys, it had to be sunk into the ground. The entire site had to be dug out to a depth of 17m by Keltbray to provide three usable levels of basements. The pit was enclosed within concrete diaphragm walls 25m high and propped by massive tubular steel beams. When the work was at its peak, 240 lorries a day transported subsoil to landscaping sites.

October 2006

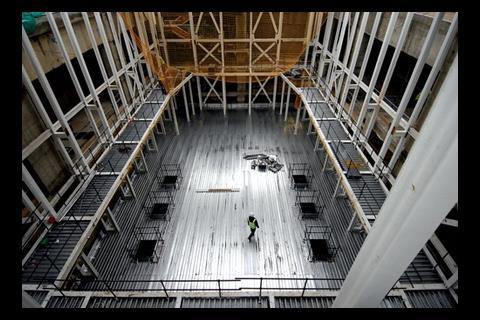

The large, column-free voids to contain the auditoria and gallery called for three large transfer structures to be cast in reinforced concrete. Above the ground-floor slab, the office floors were erected by slip-forming concrete cores to the height of the building.

November 2006

The main auditorium was built as a box within a box. The inner box was assembled from a steel frame of beams and columns. The soundproof outer box was constructed of two leaves of high-density concrete blockwork supporting a concrete lid. Then the inner box, including the steel columns, was entirely encased by specialist joinery contractor Swift Horsman in high-density fibreboard panels 50mm thick and finished in European oak veneer just 0.8mm thick. The oak veneer covering all the wall and ceiling surfaces of the auditorium, and also the doors, desks and seat backs, was cut from one immense 500-year-old tree from a forest in Bavaria.

February 2007

When it came to erecting the Jura limestone facades facing the canal, there was not enough room along the waterfront to put up the scaffolding from which to lay the ashlar on site. So after the stone was cut to size at the quarry in Germany, it was transported to Trent ConcreteŌĆÖs works in Nottingham, where it was pre-assembled into large panels with insitu concrete backing. But then, Islington traffic controllers would not allow the panels to be offloaded onto the site from the busy arterial road. Instead, the panels were offloaded from a nearby minor road on to canal barges. The barges were then floated to the side of the building and the panels lifted into position.

ŌĆ£It is very much to the credit of the contractor that it held to the spirit of the design, when it could easily have cut back,ŌĆØ says Dixon.

Project team

client Parabola Land

architect Dixon Jones

structural and services engineer and acoustician Arup

project manager and cost consultant Gardiner & Theobald

main contractor Sir Robert McAlpine

Postscript

Original print headline 'Water music'

No comments yet