Sustainable property investment funds are making big claims but not everyone is buying into the idea

This summer saw the launch of the Sarasin sustainable real estate fund, the latest of a small but growing number of property investment vehicles that are putting their money solely into green buildings. The amount of money the funds have raised from pension funds, insurance companies and wealthy individuals is small compared with the vast sums invested in property around the world, but still adds up to hundreds of millions.

The managers of these funds say occupiers are willing to pay higher rents for energy-efficient buildings because they are cheaper to run. They also claim businesses and organisations with strong corporate social responsibility policies are under pressure from shareholders and staff to occupy the greenest buildings, which makes such property more desirable and easier to let. They believe green buildings will hold their value better than others that could soon be rendered obsolete by legislation such as the Carbon Reduction Commitment and tougher �ڶ����� Regulations.

Independent property valuers are not convinced. John Symes-Thompson, senior valuation director at CB Richard Ellis, says: “There is no real proof in the UK market that green buildings are worth more.” He accepts, though, that this could change if energy costs continue to rise and further laws are introduced to cut emissions from commercial buildings, which account for 18% of the UK total.

The London-based property fund Climate Change Capital has raised £120m so far and hopes to have £500m within six years. Its strategy is to buy poor buildings in the UK and refurbish them to high standards of energy efficiency. It is seeking buildings close to public transport, let to solid tenants such as government departments or big corporations, with low flood risk and a facade with good thermal performance – “Typically, that’s masonry or brick, not glass,” says Tim Mockett, managing director of Climate Change Capital’s property team.

Glass-covered developments such as More London on London’s South Bank, where Climate Change Capital has its UK office, are not on the shopping list. The fund will also assess a building’s orientation to ensure minimal heat gain, and its cooling system to see whether a low-energy or mixed-mode version can be installed.

Early this year it spent about £26m on its first property, 5 St Philips Place in Birmingham, a six-storey office and retail building occupied by the Department for Communities and Local Government, Marks & Spencer, HSBC and Halifax. The building scored a G for its display energy certificate, the worst rating, despite winning an “excellent” under the BREEAM system when it was assessed in 2003.

The new landlord investigated how the energy meters had been set up and found that tenants were inadvertently paying for roughly double the amount of electricity used. “This is not an uncommon situation,” says Mockett. “The vast majority of existing buildings are poorly managed.” A £398,000 refund has been secured and the annual electricity bill cut from £300,000 to £168,000, raising the DEC rating from G to F.

The fund hopes to raise the DEC score further to a C or B by investing about £300,000 in air-conditioning, insulation, solar shading, lighting and controls. The tenants have agreed to use the building efficiently and to provide the landlord with quarterly reports on their energy use. The two sides are negotiating over who will pay for the refurbishments. If the tenants agree to contribute, they may receive a share of the savings in exchange or be offered a lease extension on favourable terms.

Mockett says it is difficult to say how much the value of the building will rise as a result of the changes, but when pressed says: “Our feeling is that it will be worth up to 10% more.” He emphasises that willing tenants are needed for the refurbishment strategy to work, but claims there is now no shortage of these, especially in buildings let to the public sector and big corporations.

In July the fund paid £23.9m for its second building, a mixed-used property at 3-5 Morrison Street, Edinburgh, and is drawing up plans to reduce its energy use.

The strategy of the London-based Sarasin sustainable property fund is to buy shares in property companies it considers to be the most progressive on CO2 reduction. Sarasin argues that this allows investors to get their money out quickly, as shares can be sold within hours while a building sale can take months or years.

The fund has raised €11.5m (£10.08m) since its launch in July and Jakes Ferguson, the manager, says investors are ready to commit another €30m before it is a year old. Sarasin has devised a shortlist of 64 property stocks around the world that it will consider buying. British Land is a good example: its new developments are designed to emit 25% less carbon than is allowed under current �ڶ����� Regulations and it is making serious efforts to improve the energy efficiency of its existing properties, Ferguson says. “There are other companies that are doing very, very little,” he adds.

Hong Kong is an important market for property funds, but Sarasin found only one developer that it considered green enough. The fund invests more heavily than is usual in the UK, Dutch, Australian and even US property markets because those countries are more active on CO2 reduction.

Ferguson quotes research from Jones Lang LaSalle to argue that occupiers will pay higher rents for green buildings. He claims that “a two-tier market will develop – you will end up with buildings that are simply not fit for purpose”. He admits, however, that the influence of green funds may be limited: “It’s a niche area… our clients will find this product attractive but it may never be mainstream.”

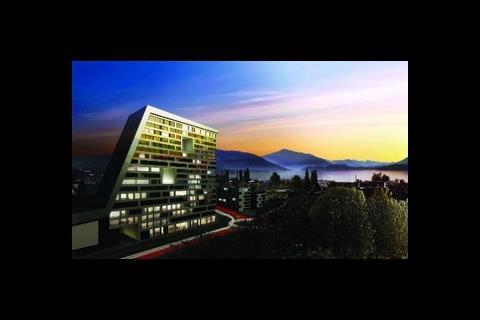

Other attempts to launch green property funds in the UK were wrecked by the credit crunch. In Switzerland values fell only slightly, however, and in April Credit Suisse was able to raise 300m Swiss francs (£173.29m) for its first green property fund. This is investing in three low-carbon, energy-efficient office, retail and residential schemes in Switzerland.

“In the long run, green buildings pay,” says Ulrich Braun, a real estate specialist at Credit Suisse. “We have a lot of experience of investing in green buildings and have found that there is relatively little extra to pay if you incorporate these features into the design from the beginning. We and at least 200 investors believe that this makes sense in the long run.”

A green building fund was launched in July by Munich-based iii investments, the property arm of HypoVereinsbank. It hopes to raise €400m within three years.

The calibre of new entrants is not enough to change Symes-Thompson’s mind about the market. Commenting on Climate Change Capital’s strategy of buying buildings for refurbishment, he says: “I would be fairly confident they will get some improved [investment] performances, but that’s very different to saying values will improve for all green buildings.”

There are many factors that make a property desirable, especially location and rent. Energy is often only a tiny part of the cost of occupying a building, ranging from 1% to 3.5% for office occupiers, according to property consultant Actium Consult.

In addition, Symes-Thompson is wary of making a direct link between energy saving and higher rents: “There’s not necessarily a direct relationship. The energy savings are part of a tenant’s operating costs and may go to a different account, while rent negotiations are conducted in the normal way.”

Investment Property Databank started a sustainability index in June to measure returns on green property. Symes- Thompson says it may be several years before enough data has been gathered to provide reliable answers. He believes the biggest property fund managers, such as Prudential, Aviva and Legal & General, are more likely to ditch their worst powerguzzling properties and improve the energy efficiency of the rest, rather than launch specialist green funds of their own.

“This agenda will affect all properties, it won’t create a separate market,” he says, adding: “Some will lead and others will be slow to adapt, and that is where you may get some differences.”

Green Property Funds

Name: iii investments Green

Fund location: Munich

Money to spend: seeking to raise €400m (£350.68m) in 2-3 years

Strategy: buy and develop office properties in western Europe, built to high BREEAM, LEED and other environmental standards

Returns: not yet disclosed, but Reinhard Mattern, the managing director, says: “Green buildings offer a sustainably higher return rate and a higher resale value”

Name: Climate Change Capital

Fund location: London

Money to spend: £120m currently available, and hopes to raise £500m

Strategy: buy poor-performing buildings in the UK and make them energy efficient

Returns: refurbished buildings likely to be “worth up to 10% more”, according to Tim Mockett, fund manager

Name: Credit Suisse Green

Fund location: Zurich

Money to spend: 300m Swiss francs (£173.29m)

Strategy: develop new residential, retail and office property in Switzerland, built to fund’s own environmental standards

Returns: “It is difficult to quantify, but in the long run green buildings should perform better than the rest,” says Ulrich Braun, head of real estate advice at Credit Suisse

Name: Sarasin Sustainable

Fund location: London

Money to spend: €11.5m (£10.08m) already raised, and further €30m expected during first year

Strategy: buy shares around the world in property companies rated as the most active on CO2 reduction

Returns: outperformed Standard & Poor’s global property index by 2% in its first six weeks, to August 31

Source

�ڶ����� Sustainable Design

No comments yet