Dormice are protected, frogs need water and bats return after removal ŌĆō just some of the challenges in dealing with British fauna and flora

01 / Introduction

Ecological features are now commonplace in building projects, either because regulators require them, or because clients wish to promote biodiversity and wildlife habitats. The range and scale of these features varies enormously. This article costs the most commonly specified solutions.

Why provide habitats?

Many animals in the UK have come to rely on urban areas for their habitats in recent years, following a loss of suburban and rural alternatives.

There are a number of reasons for this, all caused by human activity. The construction and widening of roads and other transport infrastructure tends to fragment or isolate habitats, and environmental pollution by noise, chemical or light can cause a decline in habitat quality. Meanwhile, the countryside has been affected by intensive agriculture.

Species need to move through the landscape to get between the places they use for food, shelter or breeding. Amphibians, for example, breed in ponds but hibernate in log piles so must have a way of getting between them over the year. The loss of ponds through drainage and development has caused a huge decline in some species.

The urban environment suffers from pressures such as noise, light pollution and high levels of fragmentation. However, species that can fly, climb or generally negotiate the complexities of urban areas, such as bats, birds and foxes, use urban gardens and parks to their benefit.

The value of ecology

The financial and social value of high-quality green features is well documented. Green spaces add value to residential properties and provide a social ŌĆ£feelgood factorŌĆØ.

The global value of biodiversity and the protection of eco-systems is also becoming recognised. A recent report from the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity, a UN initiative, valued the economic cost of biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation at between $2 trillion and $4.5 trillion (3.3-7.5% of global gross domestic product). This is significantly more than the economic impact of greenhouse gas emissions ($1.7 trillion) forecast in the 2008 Stern report.

02 / Protected species

The UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) is the governmentŌĆÖs response to the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity. BAP species are chosen because they are declining locally or globally. In some cases, such as the great crested newt and the greater horseshoe bat, it is the UKŌĆÖs international responsibility to protect these species.

Some BAP species, such as the water vole, are protected under national legislation. There are also protected species that are recognised at a regional level in local BAPs, such as the black redstart. All public authorities, including local planning authorities, must have regard to the presence of BAP species on a site while exercising their duties. If a species is listed on the UK BAP, we should do our bit for biodiversity by supporting it, so there is no further decline in its population. This is often a component of corporate social responsibility strategies.

Certain species are protected by law at specific times of the year. Consequently, construction works cannot be undertaken when, for example, birds are nesting.

Some species are protected by EU directives, others by UK legislation and policy. European protected species, including bats, otters and dormice, are protected from killing, injury and disturbance. Their habitat is also protected from damage and destruction.

Plan early

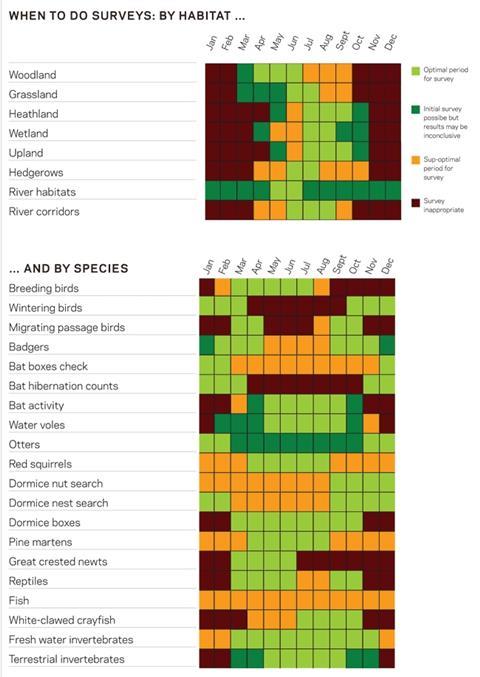

By appointing an ecologist early in the design process to survey the site, costly delays can be avoided. Ideally an ecologist should be consulted one year before the submission of a planning application. The main ecological survey season is between March and October. Think about what may be needed right at the start of the year to avoid missing critical windows for surveying particular species. The survey calendars overleaf denote appropriate timings for survey work.

Relocating species

Where species cannot remain in situ, the cost of moving animals and plants can be high. Considerations include:

- The working hours required

- The time needed to complete the work. This is typically months

- The availability of a suitable receptor site

- The management of the receptor site and capture infrastructure - for example, miles of temporary fencing.

On a very large project, 15 staff may have to work full-time for three months to move 20,000 reptiles.

Surviving the move

Relocation is a last resort when planning ecological mitigation schemes. It is rarely in the animalŌĆÖs interest to be moved to a new location. If relocation is required, having a receptor area built into your site can reduce costs and give confidence to the development timetable. Creating receptor sites in advance so the habitat is ready when required also avoids problems.

03 / Ecology credits and educational benefits

A number of relatively cost-effective credits are available in BREEAM and the Code for Sustainable Homes for creating habitats in a new development. Advice can be given by a qualified ecologist, for example a member of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management. They can survey a site and make recommendations.

In addition, credits are available for increasing the number of planted species (biodiversity) on site and for confirmation from the building occupier that they will manage the planted areas and other features (ponds, bird boxes and so on) sensitively for five years after their installation.

Planting and other features can be provided at ground or roof level, or vertically up walls and fences.

Ecological features provide great educational benefits. Pond dipping, to discover what is living in the water, entertains children and adults. Nest-box cameras give a window into the life of a family of birds. Cameras can be linked to a website to allow many people to watch a chick hatch from its egg and eventually fly the nest.

Noticeboards showing the different species supported on site can provide people with wildlife knowledge they may have missed out on before.

04 / Design and maintenance

End users might worry that ecological features will interfere with standardised maintenance programmes. For example, if nesting features are integrated into a bridge, will the owner or operator be able to gain full access to maintain it?

Designing in ecological features early on ensures that the habitat provided is attractive to wildlife and also encourages early recolonisation. This is particularly important where an existing habitat is lost. Bats and great crested newts are creatures of habit and they try to return to their previous habitats. The inclusion of new well designed features also minimises the chances of species taking up residence where regular maintenance may disturb them. Maintenance-free designs of, say, bat roosts can be easily incorporated into new buildings and other structures.

Amenity vs wildlife

Putting wildlife-friendly features into amenity areas encourages birds, bats,frogs and many other species to set up home and helps support declining populations. In turn, people who use the areas benefit by being more connected to the natural world and the amenity area provides a richer experience.

Security concerns

Lighting considerations, fencing and planting layout are typically the main issues. Again, early consultation with an ecologist ensures that conflicts do not arise too late in the design process. Use of native thorny hedging species can help to secure the boundaries of a site.

Downward-facing lighting, located to avoid light spillage on important habitats, and routing paths away from ecologically sensitive areas also help to prevent conflicts. Setting dense vegetation back from path edges to give clear sight lines improves security.

05 / Costs

Bat, bird and insect boxes

These must be located near vegetation so the target species have seeds and insects to feed on. In an urban context, Woodcrete versions of

bird and bat boxes are recommended as they are hard-wearing and less likely to be damaged. They can also be integrated into the building fabric. Invertebrate (insect) boxes are available in a variety of materials, such as timber or clay and reed.

Three bird boxes

Not to be positioned in the sun or south-facing aspect of the building

New-build costs Boxes are incorporated into the building fabric. Costs range from ┬Ż25 to ┬Ż60 a box (exclusive of VAT). Based on three boxes, supply and installation costs range from ┬Ż150 to ┬Ż250.

Existing building costs Based on three boxes, supply and installation ranges from ┬Ż100 to ┬Ż150.

Four bat boxes

Located on all four aspects of the building or a tree if available. It is important to give the bats a variety of temperature options.

New-build costs Based on four boxes, supply and installation ranges from ┬Ż200 to ┬Ż400.

Existing building costs Based on four boxes, supply and installation ranges from ┬Ż200 to ┬Ż800.

Three invertebrate boxes

Position so the boxes catch the sun for part of the day and locate in a sheltered spot.

New-build and existing costs Based on three boxes, supply and installation ranges from ┬Ż75 to ┬Ż150. Insect boxes can be installed relatively easily and installation costs may not apply.

Ground-level native species planting

Seeds and plants should be sourced from suppliers that certify their stock comprises UK native species and is from UK stock.

Wildflower meadows The ground must be prepared in advance of planting. Management includes three cuts in the first year and then an annual cut of the meadow, and removing the cuttings. Ground preparation, supply and sowing of a 100% wildflower seed mixture has an average cost of ┬Ż1.50/m2.

Hedgerow Hedgerow should be planted at four shrubs per metre and include a mix of British native hedgerow plants. Occasional trees should be planted - about one every 30m. Buy 600-700mm whips (one and two-year-old nursery stock). Based on native plants, the average cost is ┬Ż10/m.

Trees Supply and install ash (common), 250-300mm girth, ┬Ż1,250 a tree. Supply and install beech (common), 250-300mm girth, ┬Ż1,400 atree. Supply and install oak (common), 250-300mm, ┬Ż1,500 a tree.

06 / Living roofs

Extensive biodiverse roofs are low maintenance and should not usually be given public access. Typically, plants require maintenance only until established. Associated infrastructure, such as barriers, gutters and drainage points, requires maintenance, however. Occasional visits (about once a year) are required to remove invasive plants such as buddleia or tree saplings. No irrigation is required. The roof may dry out in thin areas and will not be a lush green colour but this creates a mix of ecological niches.

A biodiverse roof has the following layers:

- Vegetation

- Growing medium, soil or substrate

- A filter sheet (geotextile or similar) to allow water to drain but retain finer soil material

- A drainage layer (lightweight gravel or other) designed to drain excess water. This can also include a ŌĆ£reservoirŌĆØ system to retain water in a moisture mat

- A root barrier

- A waterproof membrane to prevent water damaging the building

- A roof buildup including insulation, vapour barrier (if needed) and roof deck.

The substrate must absorb and hold water, contain some organic matter, supply basic nutrients and not be too heavy. For example, a mix of crushed brick and concrete with some organic matter, and some coarse gravel/pebbles and coarse sand to give a variety of substrate types (see below).

A biodiverse roof also has the following key features:

- Planting in a substrate, not a sedum mat

- Use of a variety of depths of substrate to provide a range of habitat niches

- Incorporate an assortment of substrate types to include areas of sand, gravel or crushed, inert, recycled crushed demolition waste (pieces no larger than 50mm)

- Use a variety of native species in the planting on the roof and include species with a variety of growing heights and structure

- Additional features such as a few logs are important for invertebrates and can provide perches for birds. The logs must not have been treated with chemicals and therefore must not be railway sleepers. Recycled logs felled from site are ideal.

A typical substrate profile would be 75-200mm deep: 50% at 75mm, 30% grading up to and including mounds of 150mm, 10% should be 200mm mounds and 10% areas of coarse gravel and sand. Vegetation planting could include wildflowers and grasses.

Living roofs cannot typically be applied to existing buildings unless it is known that the existing structure can accommodate the additional weight of the substrate and captured rainwater.

Costs Waterproofing membrane with 120mm root bar protection layer, extruded polystyrene with separator layer, drainage board with filter sheet, a substrate with an average thickness of 120mm and wildflower seeding. Average cost: ┬Ż85/m2.

Blue roofs

A blue roof has a slightly deeper substrate than a green roof. Ideally, 30% of the roof is a pond area (300mm deep), 40% is marsh (200-300mm deep around the edge of the pond) and 30% is substrate (75-200mm deep). The deeper substrates contain more organic matter and retain more rainwater (creating marshy habitat) so the combined additional loadings can increase the buildingŌĆÖs structural costs. A blue roof has the same layer design as a living roof (see above).

Planting should consist of wetland plants and seed mix.

Costs Waterproofing system, insulation and drainage board, EPDM pond liner, 300mm crushed brick, 300mm deep extensive substrate for marshland, average 135mm extensive substrate, wildflower seeding

- Total average cost ┬Ż100/m2.

- Pond area (30%) ┬Ż105/m2

- Marsh area (40%) ┬Ż125/m2

- Extensive substrate (30%) ┬Ż85/m2

Green walls and climbing plants

Climbing plants should be grown on a frame fixed to a wall with no windows. They require a deep (ideally greater than 1m) planter at the base of the wall. The planters require irrigation. The wall-mounted trellis should be a minimum of 5m high. Some climbers require pruning and tying into the frame. Plants such as ivy, honeysuckle and climbing roses are good options. Ivy is the only native species that is shade-tolerant.

Costs for planter A 3 x 1 x 1m deep planter with brick walls, base, waterproofing, topsoil and compost; supply and installation of basic trellis; plants as above. Average cost: ┬Ż850

Cost for green wall Green wall costs vary considerably based on the size of wall being planted. Costs reduce notably as the wall size increases. Average cost: ┬Ż500/m2.

07 / Sustainable drainage ponds and swales

Ponds can range in size from 1m2 to 300m2 to fit site requirements. Groups of small ponds are better than one large one. Pond margins should always be gently sloping (at least 1:5 and preferably 1:100) and no fish should be added. The pond lining is covered with substrate for pond vegetation to grow in. The substrate should be an inert low nutrient material and must not be topsoil. Hummocks and hollows should be designed into pond margins above and below the waterŌĆÖs edge.

Shallow ponds provide habitat for insects, amphibians and other wildlife and are also more likely to dry out, preventing the establishment of fish, which tend to eat everything else. Large pond designs should include low lying islands. Broad, almost flat, undulating wetland areas around and between ponds are ecologically valuable and provide sustainable drainage benefits. Hummocks should be created in the base of the pond.

Any pond should have a 2m vegetation buffer around it and piles of stones or logs can be placed around the pond to create hiding places for animals. These can be structured in a way to make them visually attractive as well as ecologically valuable. Surrounding vegetation should not have fertiliser applied to it. Ponds should be sited away from large trees and new trees should not be planted immediately next to ponds.

Ponds require management in the early years but do not need long-term management if correctly designed and planted. Invasive species can occasionally appear and these need professional eradication. Invasive species are only likely to be a problem in urban areas from birds or members of the public adding things to the pond.

Ground contamination must be remediated before creating any wetland features.

Planting species must be native to the UK and typical of the locality - an ecologist must be consulted for each situation. Good choices include water plantain, flowering rush, water mint, water forget-me-nots and water speedwells. Plants must be sourced from suppliers who provide a warranty that the material is free from alien species.

Costs The excavation of pond area, the installation of liner and site-won backfilling material, marginal planting around the edges. Average cost: ┬Ż40/m2

Swales

Swales - shallow grassland depressions - are often a component of sustainable drainage proposals. They provide temporary storage for storm water and reduce peak run-off flows. A series of dry and semi-dry wetland area/reedbed and detention basins can be incorporated into landscape and drainage strategies. They contribute to nature conservation opportunities and habitat development, as well as supporting site amenity and drainage. The margins of these ponds and basins should be carefully designed to ensure they have a natural appearance and integrate seamlessly with the surrounding environment. The swales should incorporate grassland species tolerant to intermittent inundation.

Costs Excavation of swale area, marginal planting around the edges, hand-sown wildflower or grass mix to prepared surface: average cost ┬Ż20/m2.

Appeared with headline Sustainability wildlife in ║┌Č┤╔ńŪ° magazine

Source

Isabel McAllister, Pete Dowbiggin and Chris Dibsdall work for Cyril Sweett while Ruth Fletcher and Richard Graves are with AECOM

No comments yet