If an adjudicator has a prior connection with one of the advocates arguing a case, does that constitute ’apparent bias’? Here’s what the court had to say …

Folk fret about the ref in a football game being biased, or rather, being biased in favour of the other side. It sometimes also happens that judges, arbitrators and adjudicators receive a Paddington Bear stare when there is the slightest hint of bias.

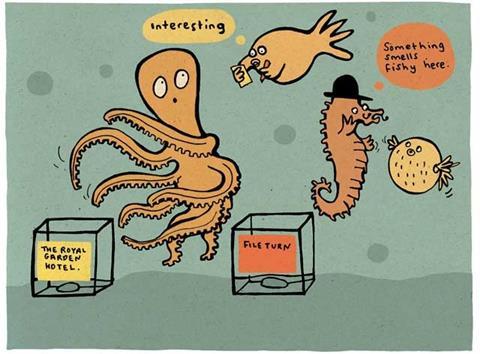

In one adjudication case, one party - the Royal Garden Hotel - did just that. The hotel was told in May to pay Fileturn, its high-quality refurbishment contractor, £220,000. But the hotel’s lawyers did a bit of digging. Perhaps they got a sniff of a connection between the adjudicator and the representative for Fileturn.

Even I know that the well-known adjudicator was once a partner in the same firm of consultants as the well-known representative. It doesn’t surprise me he was appointed

Even I know that the well-known adjudicator was once a partner in the same firm of consultants as the well-known representative of Fileturn. It doesn’t surprise me that the representative of the contractor asked for this adjudicator to be appointed. I too would have asked for him: he is an independently minded fellow who knows his stuff. There would be another reason for asking for this fellow: the representative of Fileturn has been represented in hundreds of adjudications and knows from bitter experience that some adjudicators are less on the ball than others.

Royal Garden asked the court to set the adjudicator‚Äôs decision aside and declare the whole process a nullity. There was, it said, a ‚Äúprevious association‚ÄĚ between the adjudicator and the representative, which it claimed gave rise to apparent bias.

Note that the complaint is not about the referee having some link, association or relationship with one of the parties. No, it’s about having a relationship with the firm representing one of the parties.

That representative relationship argument is a tough nut to crack on grounds of bias. Bias - or rather, complete absence of bias - is a fundamental and crucial ingredient for anyone who judges or assesses anything. The test for apparent bias is well known. It is the test that asks whether the circumstances would lead a fair-minded and informed observer to conclude that there was a real possibility the adjudicator was biased.

Notice that it need only be ‚Äúpossible‚ÄĚ that these circumstances might incline the bloke to favour or disfavour a party. And that test is about circumstances that signpost bias. It may not even have dawned on the assessor, judge or adjudicator that the circumstances indicated bias. It‚Äôs an objective bystander test; it asks the audience whether there is a mere chance of leaning one way or the other.

That’s quite a different type of bias to having an interest in the outcome - that’s actual bias, which is not suggested at all in this case. The adjudicator in question is a barrister who in 2001 became a director of a building contract disputes consultancy. After three years he left to become a partner in a firm of solicitors, eventually moving on to form his own firm, where he has done well.

In the intervening years, like many experienced adjudicators, he has been asked for by name or profession. There‚Äôs nothing wrong with that. It has long since been decided by the High Court that asking an appointing body to slot a particular person in place is by no means ‚Äúselecting‚ÄĚ the adjudicator. The selection is done by the appointing body, irrespective of any name suggested.

In fact there is judicial support for lobbying for a particular adjudicator or arbitrator or qualification. ‚ÄúIt is not necessarily wrong or unhelpful for a party to make representations. For instance, if the dispute is technical - say, involving thermodynamics - it might be very sensible for the nominating body to be so informed‚ÄĚ.

The same goes for guidance on conflict of interest. But it’s not much good indicating conflict or bias between tribunal and representative. Client, yes; representative, no.

In the Royal Garden Hotel case, the court was clear: there was no chance an informed observer would conclude that the previous business relationship of the adjudicator and representative indicated a apparent bias.

The experienced adjudicator knows full well they are there to decide a quarrel between the parties; as to who turns up to argue the case is of no concern. Good job, too.

Tony Bingham is a barrister and arbitrator at 3 Paper ļŕ∂ī…Á«Ýs Temple

No comments yet